War, Vinyl and Print: Music for the Troops during World War II

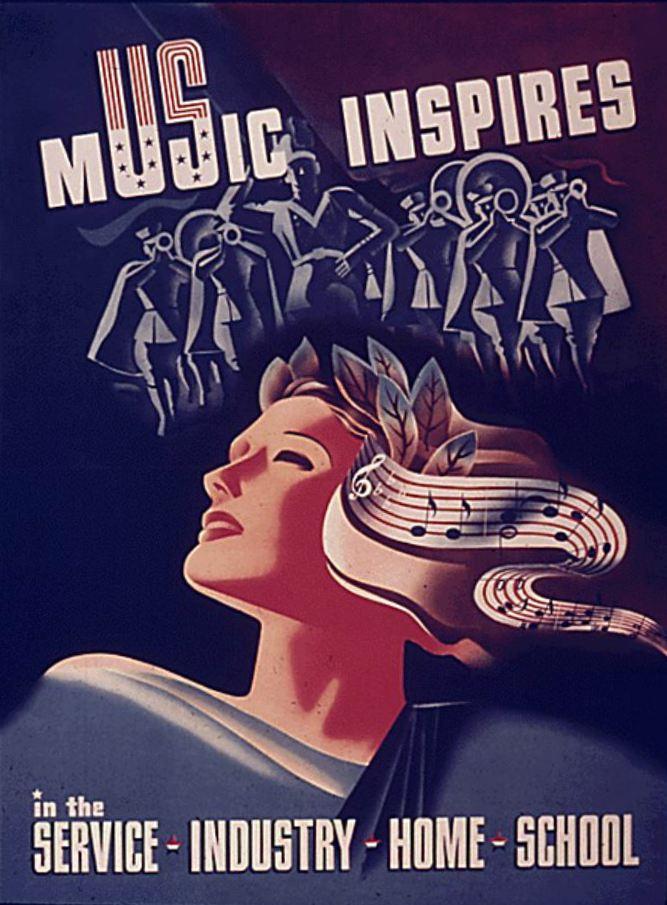

Music Inspires in the Service - Industry - Home - School, World War II Poster, 1941–1945. Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, Bureau of Special Services.

NARA (National Archives and Records Administration), Photographs and Graphic Works, College Park, MD, 44-PA-1377

Music Inspires in the Service - Industry - Home - School, World War II Poster, 1941–1945. Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, Bureau of Special Services.

NARA (National Archives and Records Administration), Photographs and Graphic Works, College Park, MD, 44-PA-1377

“Saturday night I asked my two tent mates if they would like to hear some good music. Yes. We brought down the machine and some of the wonderful records which you sent along. Lowbrowly, we first put on Dinah Shore singing that tantalizing Mood Indigo. It wasn’t on three minutes before a Major came tumbling in from a nearby tent demanding to know what kilocycles we were on; he had been frantically trying to get the music on his radio. We laughingly explained what it was all about. Off he rushed to turn off his machine and back he came to stay all evening. A helter-skelter programme proceeded. While Finlandia (cracked but acceptable) was playing, a Lieutenant wandered in. . . . . Soon the tent was crowded.”

(Letter from Marine officer “Ray” to Harold Spivacke, chief of the Music Division of the Library of Congress and leader of the Subcommittee on Music for the Joint Army and Navy Committee on Welfare and Recreation, March 20, 1944.)

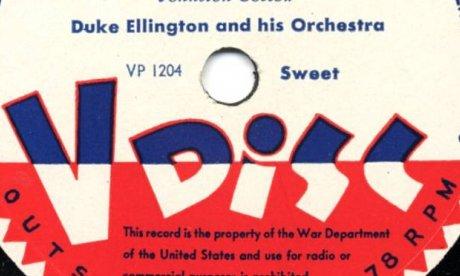

While vinyl records, nostalgic remnants of the 1950s-1980s, have a cult following today, many may not realize that one of the first, widespread uses of vinyl records was spurred by the U.S. military during World War II (1941-1945). Capitalizing on modern technologies and the potential of music to entertain on the one hand, and provide moral uplift and education on the other, the Army Special Services initiated “V-Discs” (the V stood for “victory”) to boost troop morale in 1943. V-discs—typically 12-inch, 78 rpm gramophone records—could hold over six minutes of music per side and featured popular, folk, and classical selections, often specially recorded for soldiers. Packed in waterproof boxes complete with replacement needles, more than 3 million V-discs were shipped to U.S. troops. Hand-cranked record players brought alive the recorded sound.

Why vinyl, and not shellac, the typical material of 78 rpm records of the time? Vinyl proved a more practical option: not only are shellac records quite fragile, but shellac itself—a resin secreted by the lac bug (native to India and Southeast Asia)—was difficult to obtain in wartime. The U.S. Armed Forces’ early use of vinyl preceded by several years its mass commercial use.

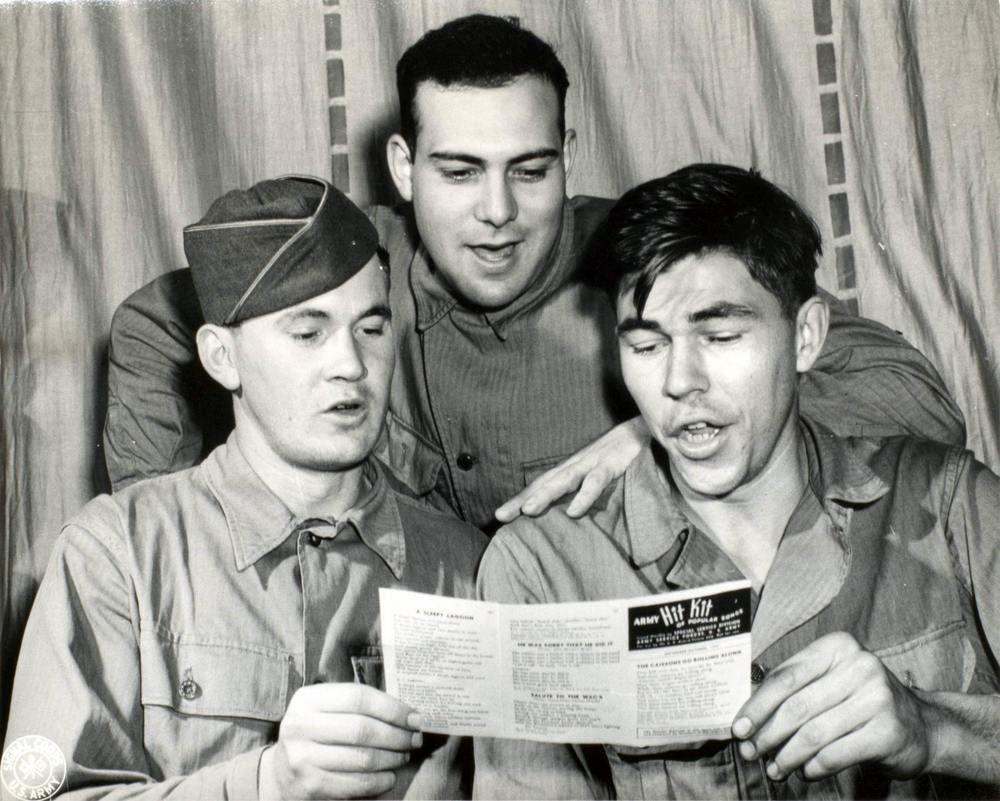

Annegret Fauser’s recent book, Sounds of War, reveals the forgotten history of how the armed forces supported music and music-making for strategic purposes, such as fostering community among the more than 10 million individuals inducted into the military. Her research shows, for example, that the army relied not only on new technologies like recorded sound and V-discs, but also on a much older technology—printing. Seeking to promote recreation and unite soldiers, the military distributed publications like The Army Hit Kit—a collection of national, folk, popular, and patriotic tunes—on a massive scale. By 1944, 2.4 million copies of this publication were distributed to troops each month. Newer media formats—records, slides and film shorts of the songs—often accompanied the printed song sheets. The slides made projection of lyrics on mess hall walls possible, while “music officers” coordinated music events and arranged for song-leader training and instrumental instruction at military posts.

Sounds of War details how musicians worked with the U.S. military, the State Department, and the Office of War Information to further cultural diplomacy, support propaganda efforts, create community, and commemorate the dead. Fauser culls insights from more than 20 archival collections (e.g., Archives of the Office of War Information, Records of the Joint Army and Navy Committee on Welfare and Recreation, and the papers of individual musicians like Aaron Copland and Oscar Hammerstein II), illuminating the musical engagement of American soldiers and civilians well beyond the walls of the concert hall.