Two Americans in Paradise: Henry Adams and John La Farge on the Island of Tahiti

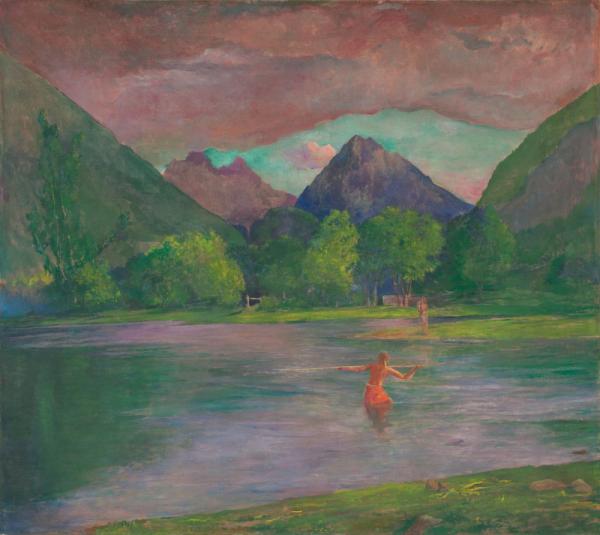

John La Farge, The Entrance to the Tautira River, Tahiti, circa 1895, oil on canvas, 53 1/2 x 60 inches.

Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Adolph Caspar Miller Fund, 1966.6.1

John La Farge, The Entrance to the Tautira River, Tahiti, circa 1895, oil on canvas, 53 1/2 x 60 inches.

Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Adolph Caspar Miller Fund, 1966.6.1

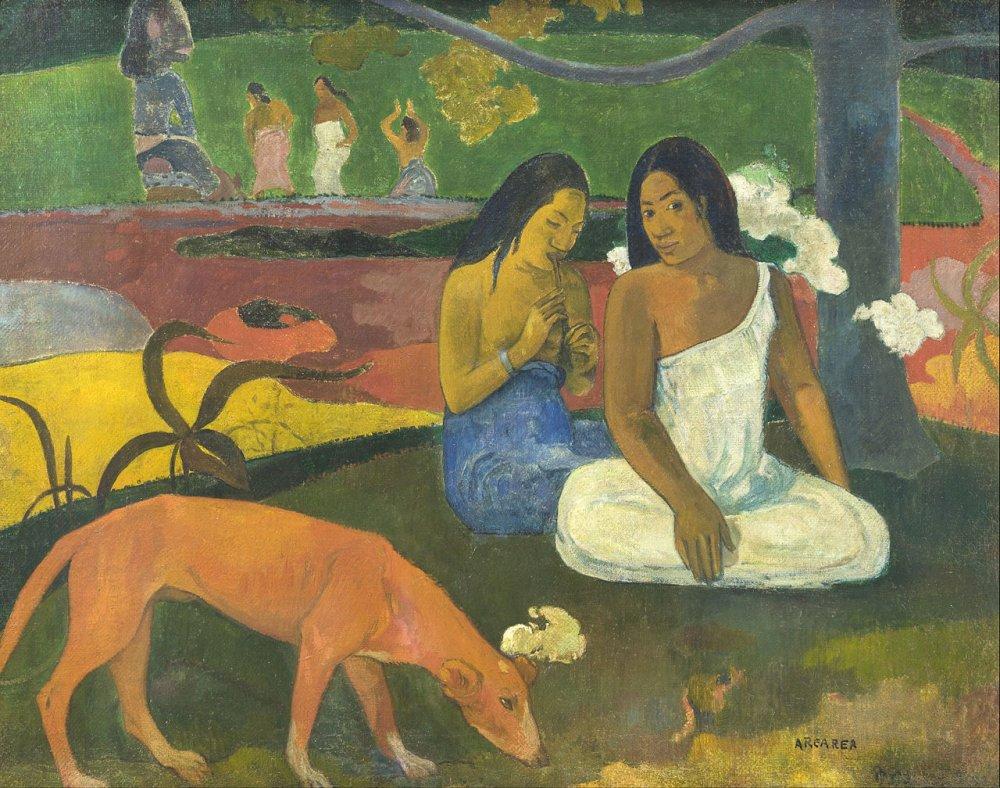

In 1891, Paul Gauguin, the friend and sometime rival of Vincent Van Gogh, traveled to Tahiti and began to create the famous paintings that evoke visions of exotic natural beauty and mysterious island culture. Yet from February to June, for four months before Gauguin arrived, two Americans sought to explore the “real” Tahiti, to experience its landscape and understand its history. One was a wealthy intellectual, the other a painter.

Henry Adams (1838-1918), grandson of President John Quincy Adams, was a prolific historian and writer, perhaps best known for his memoir The Education of Henry Adams (1918). Adams loved to travel, and the stay on Tahiti was part of an extensive journey through the South Pacific and Asia. He was inspired by earlier accounts of the island, such as the journals of Captain James Cook and Herman Melville’s novels Typee and Omoo, as well as the popular romance, The Marriage of Loti, by Pierre Loti. Although Adams did not find the tropical paradise he expected, he was soon drawn into the local culture much more deeply than a regular tourist. He befriended several indigenous leaders and conducted ethnographic investigations, which resulted in a publication on the Salmon/Brander family of the Teva clan and their venerable queen, Arii Taimai, in 1901.

John La Farge (1835-1910) accompanied Adams on his travels, the latter paying for his expenses. La Farge had distinguished himself as a muralist and stained glass artist through works in numerous churches and public buildings of the United States. He was an erudite, academically trained painter, influenced by the romantic scenes of English Pre-Raphaelites and, more recently, the asymmetrical landscape compositions of Japanese prints. As Elizabeth Childs writes in her book, Vanishing Paradise: Art and Exoticism in Colonial Tahiti (2013), La Farge experienced Tahiti physically and visually, by walking, hiking, and canoeing, all the while sketching and painting watercolors. More surprising, she discovered that he also relied heavily on colonial photographs he had purchased to compose a series of South Seas paintings, idyllic views that brought him acclaim at home after his return. Employing glowing colors, La Farge’s genteel and idealized works express what Childs terms his “nostalgic regret.” They offer a far different vision of Tahiti than Gauguin’s images – hard-edged, raw, and avant-garde – with bright flat colors that reveal the textured burlap canvas.

Childs concludes that both Americans were inspired by their Tahitian experience, but not in the way they had originally expected. She analyzes the multi-layered opinions about place, history, and culture that these “elite ethnotourists” imposed on the island. In their notes and letters, Adams and La Farge observed a melancholy and listlessness pervading the island population that they found dispiriting. They lamented the disappearance of what they considered an authentic and ancient culture and landscape, threatened by encroaching modernity. Through their writings and art works Adams and La Farge sought to retain and visualize what they perceived as a vanishing paradise.