The Horoscope of St. Peter’s

Saint Peter’s Basilica as it stands today is the collective result of at least ten artists and architects who worked under the auspices of twenty-one different popes.

This image is in the public domain

Saint Peter’s Basilica as it stands today is the collective result of at least ten artists and architects who worked under the auspices of twenty-one different popes.

This image is in the public domain

Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, an emblem of the Catholic Church, is considered by many to be an enduring affirmation of a centuries-old theology and a grand example of Renaissance architecture. Astrology, however, may not come to mind immediately for the millions of visitors who take in the spectacle of the awe-inspiring building each year. The construction of the church—a project plagued by a more than a century of financial woes and construction delays—was in fact begun on a certain date and at a precise time, a moment carefully chosen for its astrological significance.

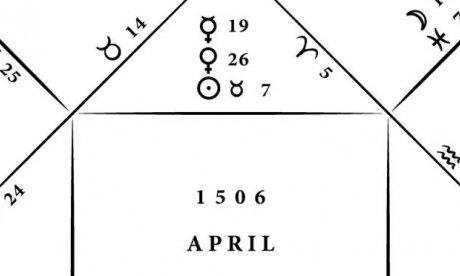

The astrologers of Pope Julius II established that the horoscope of April 18, 1506, at 10:00 a.m. correlated with both the horoscope for the presumed birth of the world and the birth horoscope of Christ. In addition, the locations on the horoscope chart of the Sun, Venus, and Mercury indicated benevolence, while that of Saturn and Mars suggested power and longevity. Jupiter’s location was propitious as well, promising wealth. Julius and his Renaissance architects believed that the concordance of the heavens and the radiation emanating from the cosmos provided protection for this building at the time of its founding and, in turn, the building would continue to radiate these powers upon the people associated with it for centuries.

In her recent book Influences: Art, Optics, and Astrology in the Italian Renaissance, Mary Quinlan-McGrath examines the astrological context of the founding of Saint Peter’s as well as the creation of other works of art and architecture in Rome, such as the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican Palace—home to Raphael’s famous School of Athens—and the lavish Villa Farnesina of Agostino Chigi, an extremely wealthy banker. She demonstrates that astrological thought permeated the Italian Renaissance. Scientists used mathematical measurements to chart the heavens, and theologians and philosophers harmonized religious doctrine with astrological readings, making Saint Peter’s a product of its time. The belief that celestial forces could operate through works of art and architecture was not obscure or magical, but in harmony with the philosophical, religious, and scientific beliefs of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.