Looking for the Antichrist: A Sign of the Times in Rome

Edith and Ralph Norton, about 1930.

Courtesy of the Archives of the Belgian Evangelical Mission, preserved at Evadoc, Leuven (Belgium)

Edith and Ralph Norton, about 1930.

Courtesy of the Archives of the Belgian Evangelical Mission, preserved at Evadoc, Leuven (Belgium)

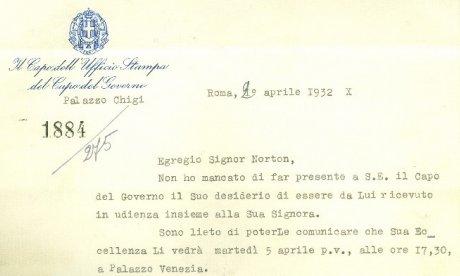

“Do you intend to reconstitute the Roman Empire?” It was a simple question, but Il Duce did not understand.

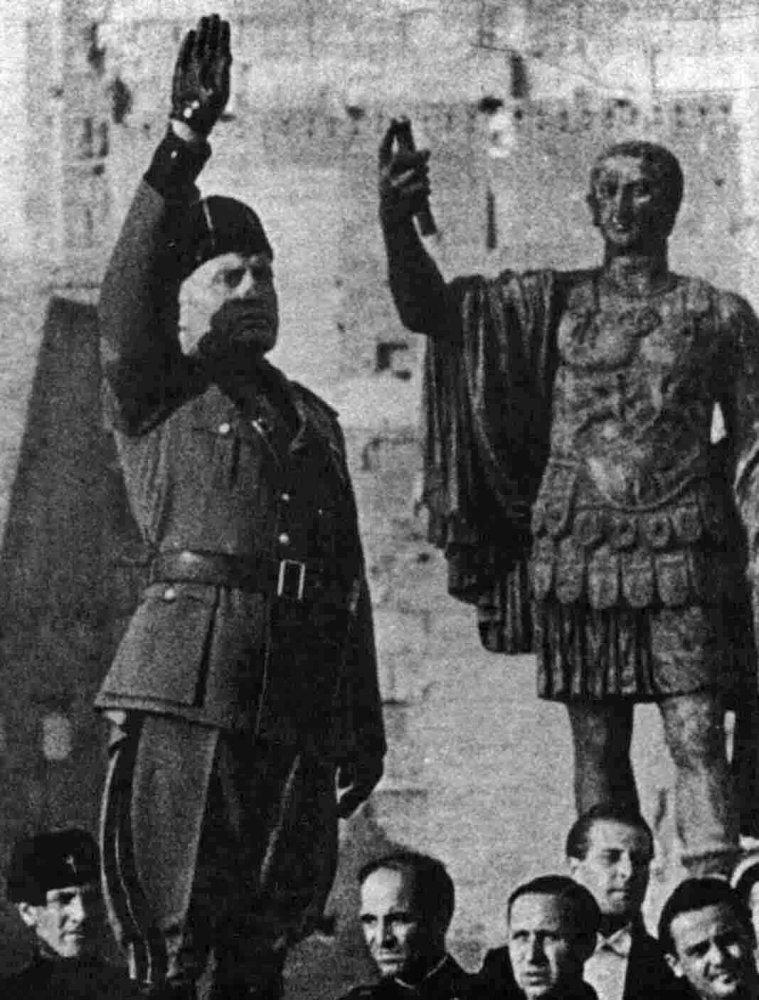

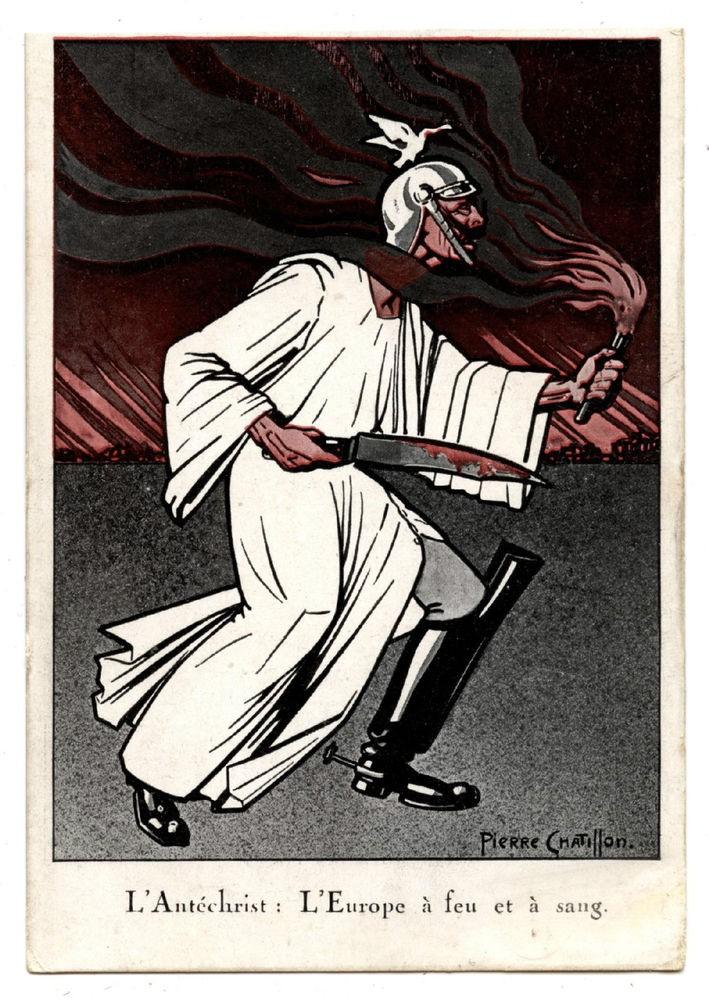

The question was posed during a 1932 meeting between the American evangelical missionaries Edith and Ralph Norton and the rising Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, also known as Il Duce (The Leader). The Americans explained to Mussolini what many of their evangelical brethren believed: the end was near. According to the Nortons’ reading of Biblical prophecy, Jesus’ Second Coming would be heralded by the nations of the earth banding together in a global, ungodly confederacy. At the head of the coalition would rule the figure known only as ‘the Antichrist,’ a terrible dictator who was destined to be defeated by Jesus in the battle of Armageddon, bringing about a thousand years of peace and joy. When Americans heard about an Italian dictator uniting Italy, some could not help but think that the Roman Empire would return, and with it the end of days.

Il Duce’s curiosity was piqued. “Is that really described in the Bible? Where is it to be found?” The answer, the Americans pointed out, lay in the book of Daniel, the Hebrew prophet whose visions provide the basis for historical and contemporary Biblical prophecy regarding the Antichrist and Jesus’ Second Coming. But the Nortons’ plan to deter Mussolini backfired spectacularly; upon being shown the passages, Il Duce was apparently much pleased. The role of global dictator was one he would gladly assume. Although an atheist, he wondered if, perhaps, his rise to power truly was foretold. One can only imagine the missionaries’ disappointment.

The Nortons, who had founded the Belgian Evangelical Mission in Brussels after World War I, were not alone in their apocalyptic beliefs. From the early nineteenth century to the present, from Billy Sunday to Billy Graham, a strand of Evangelical thought has focused on current events in light of prophecy. Mussolini was not the only suspected Antichrist; during World War I, Kaiser Wilhelm seemed a likely candidate. At other times, it appeared as if he might be a Bolshevik leader. The Nortons and others believed the signs of Armageddon were there, even if sometimes unclear.

Matthew Avery Sutton's recent book American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism traces the development of American evangelicalism, particularly the role of apocalyptic thinking in its life and work. Not all evangelicals anticipate an imminent apocalypse or see the next Antichrist in the latest dictator. Sutton's work shows, however, that history both has and is meaning for evangelicals; it is the hand and mind of God made manifest in the world. This evangelical obsession with history--both its ends and its End--has shaped American culture and Americans' view of the world.