High Life in the Bronze Age

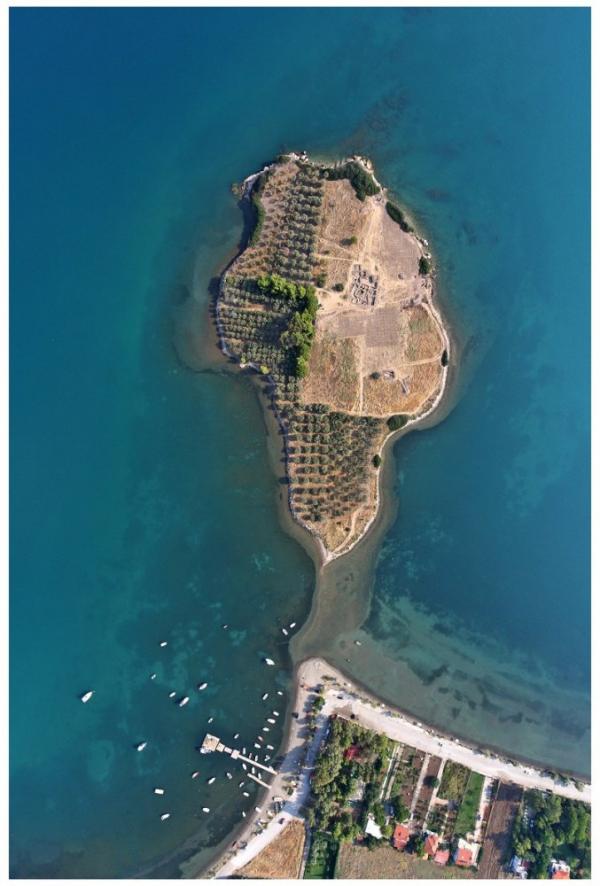

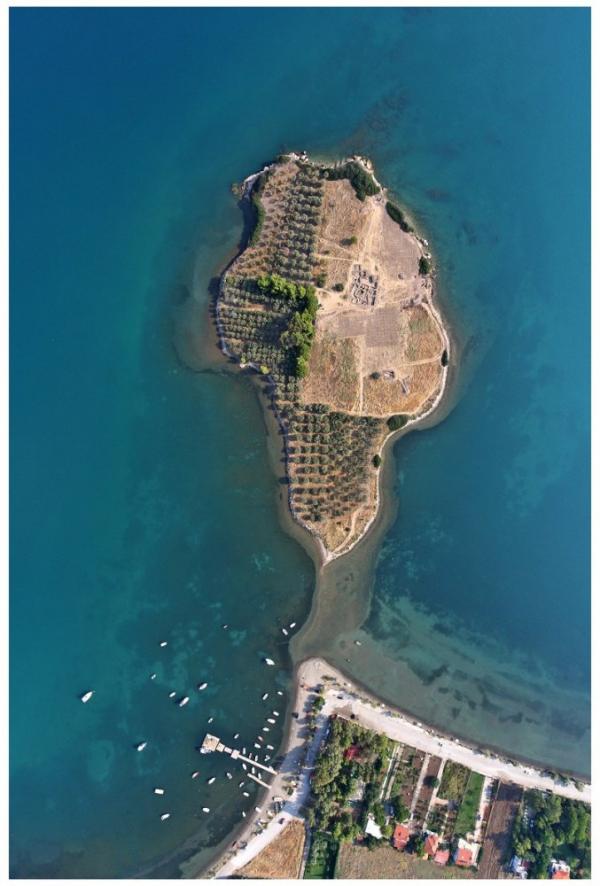

Mitrou is a small island near Tragana, in the bay of Atalanti, East Lokris, Greece.

Photo: K. Xenikakis and S. Gesafidis; Courtesy of the Mitrou Archaeological Project

Mitrou is a small island near Tragana, in the bay of Atalanti, East Lokris, Greece.

Photo: K. Xenikakis and S. Gesafidis; Courtesy of the Mitrou Archaeological Project

First class seats. Designer labels. Gated communities. Society’s elites find ways to distinguish themselves from the rest of the world. This is not, of course, a recent phenomenon. Roman patricians wore purple-trimmed togas, medieval rulers built castles, and wealthy people of the Renaissance commissioned fine art, but archeologists have discovered some of the earliest evidence of conspicuous consumption on the small Greek islet of Mitrou, where aspiring leaders in Bronze Age Greece (around 1600-1400 BCE) reshaped their society to set themselves apart from other people.

Excavated by an international team led by Aleydis Van de Moortel, Professor of Classics at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Mitrou sits on the Gulf of Atalanti about a hundred miles north of Athens. While it is a mere 1,100 feet long and 600 feet wide, the site served as a local administrative center linking trade routes between the Eastern Balkans and the larger settlements in Greece. Mitrou provides important lessons for archaeologists interested in Greek elites and social and commercial development across the region.

Together with Eleni Zahou of the Greek Archaeological Service, Van de Moortel and her team have discovered a variety of structures and objects that offer hints of how Mitrou’s leaders reshaped their community. In the Middle Bronze Age (2000-1600 BCE) the islet was a village with narrow roads. After 1600 BCE, however, residents started building paved and plastered roads as much as nine feet wide, which may have had restricted access. The team also found a bridle from the same period, designed to be worn by a horse pulling a chariot. These chariots, like the luxury cars of today, conveyed status—and required wider paved roads.

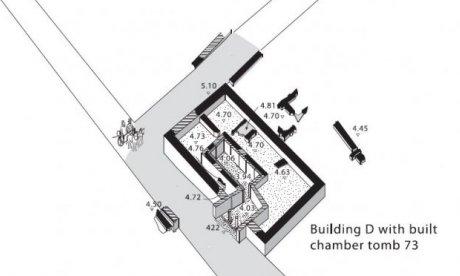

The emerging upper classes changed burial practices as well. It had long been traditional on Mitrou to bury your family’s deceased on your property, but that pattern shifted around 1600 BCE with the creation of a communal cemetery on the edge of the settlement. Yet Van de Moortel and her colleagues discovered that one of the elite groups on the islet built an elaborate tomb in its own building complex, a private burial separate from the community plot. This tomb, she argues, is yet another example of elite exceptionalism.

Mitrou’s leading citizens set themselves apart from the rest through megalithic architecture—using large stones without mortar—and fine lime plaster floors. Clothes and food were further distinguishing social attributes. The archaeologists found shells from the Murex snail used to create a purple dye for garments long associated with wealth and nobility. The discovery of specialized ceramics—imported cookware and fine dining pottery—suggests the development of a refined cuisine, indicating that the elite enjoyed dishes not available to the rest of the population.

The people of Mitrou lived millennia ago, in a very different time and place, but they had their equivalent of designer clothes, upscale dining, and fancy cars. Their chariots and cemeteries helped to forge a differentiated social structure, marking the rise, in Mitrou and elsewhere, of complex and hierarchical societies during the Bronze Age.