Heartbreak at Menlo Park

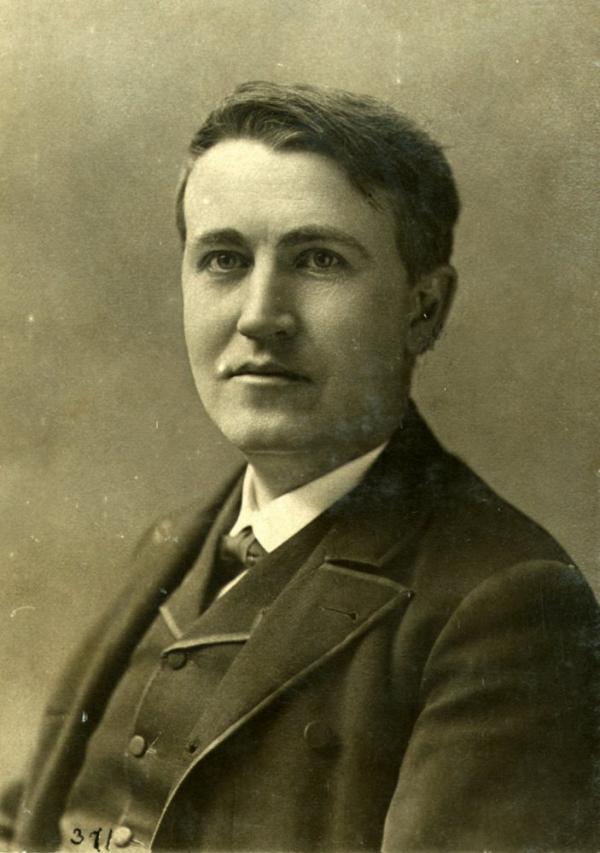

Thomas A. Edison in 1884, the year his wife Mary died.

New York Public Library, New York

Thomas A. Edison in 1884, the year his wife Mary died.

New York Public Library, New York

Thomas Edison famously said that "genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration." Edison's genius led to the development of technologies that we could hardly imagine living without today. The Papers of Thomas A. Edison project gives us a much better sense of the perspiration that went into the development of those technologies and Edison’s business decisions. More surprisingly, perhaps, they reveal much about his personal life, too, humanizing the inventing dynamo.

Volume 7, Losses and Loyalties (2011), covers the months from April 1883 through December 1885, and contains documents from one of the most tragic events of Edison's life: the death of his first wife, Mary Stilwell Edison, at a young age. The book includes the only contemporary profile of Mary: a newspaper article, "In the Wizard's Home," by Olive Harper from New York World (June 1, 1884). Her telling contradicts the oft-told story of her courtship with Edison, gilded as a whirlwind affair between the inventor and one of his factory employees.

As Mary tells it, she was a schoolgirl of fifteen at the time of their first meeting, but tall for her age. She met Edison by chance when she took refuge in one of his factories during a rainstorm. She noticed Edison for "two reasons … he had very handsome eyes… and he was so dirty, all covered with machine oil, etc." Edison walked her home and visited with her family. At first, Mary was the reluctant object of his affection, but with her father's permission, they began courting in the spring of 1871 and were married on Christmas day that year. She was 16, he was 24.

Mary recounted that during her years with Edison "she never feels neglected when her husband shuts himself up at Menlo Park for the purpose of making experiments or for invention, and she just waits until he has emerged from his seclusion, only taking pains to see that he has his meals properly." Mary does complain, however, that "with all Mr. Edison's success with electricity their home is still lighted with gas, to her disgust and vexation."

Sadly, two months after this article appeared and after just thirteen years of marriage, Mary died suddenly at age 28. The volume contains telegraphs exchanged between Edison and his secretary, Samuel Insull, arranging for an undertaker on the day she died, August 9, 1884. The exact cause of Mary's death is not known, though it was initially described as "congestion of the brain."

An essay in the volume written by the project staff sheds new light on a possible cause of death. In New York World, it was reported anonymously (probably by Olive Harper) that Mary died from a morphine overdose. New research has uncovered circumstantial evidence that an overdose is plausible since Mary was being treated for chronic pain. "Congestion of the brain" was a commonly noted symptom of a morphine overdose.

Edison's ten-year-old daughter, Marion, became his constant companion during the next several months, and the book includes an account by The Electric Review that observes them at a Philadelphia electrical exhibition in September: "it is a pathetic sight to see them going about hand in hand, the observed of all observers."

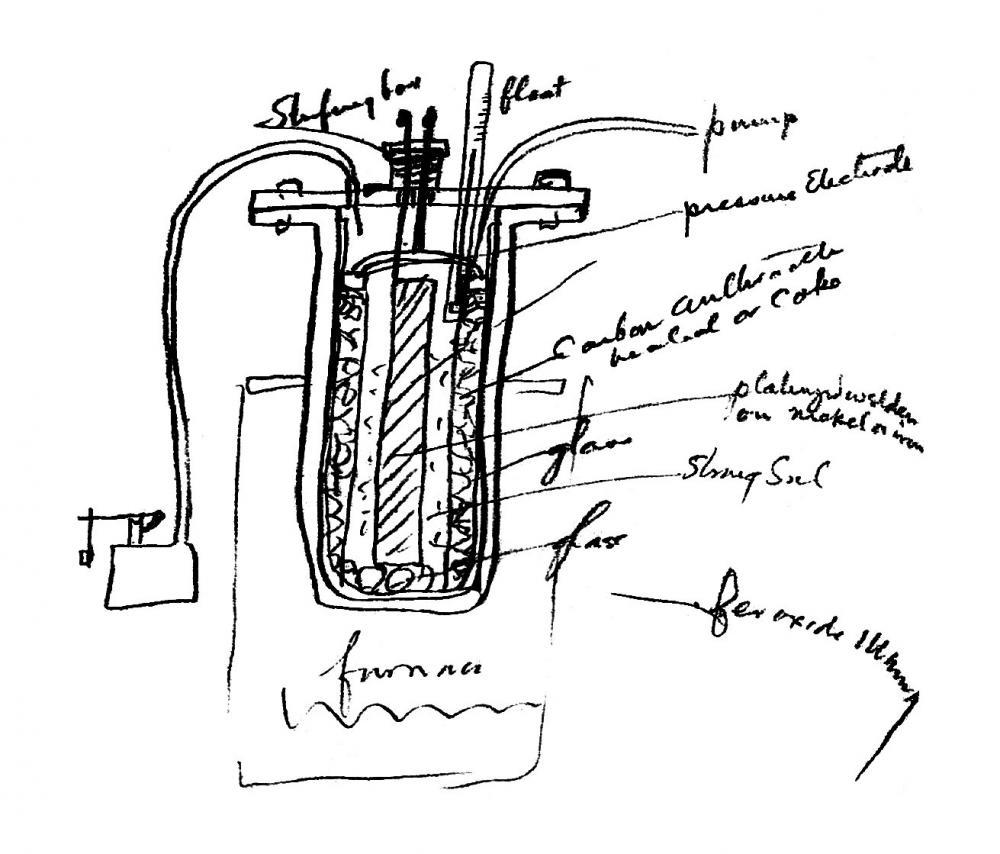

The Edison volumes are visually compelling. They include patent schematics, hand-drawn sketches of inventions in progress from Edison's notebooks and memos, black and white photos, and line art illustrations from the period. The volumes also contain many brief editorial essays to provide context for the events of Edison's life and work during these months.

Johns Hopkins University Press will soon publish volume eight of the series. When completed, the print edition will span fifteen volumes and contain some 6,500 letters, notebook entries, drawings, patent applications, legal documents, marketing plans, and autobiographical essays. An unannotated, digital-image edition is available at http://edison.rutgers.edu/digital.htm.