Captured by Pirates

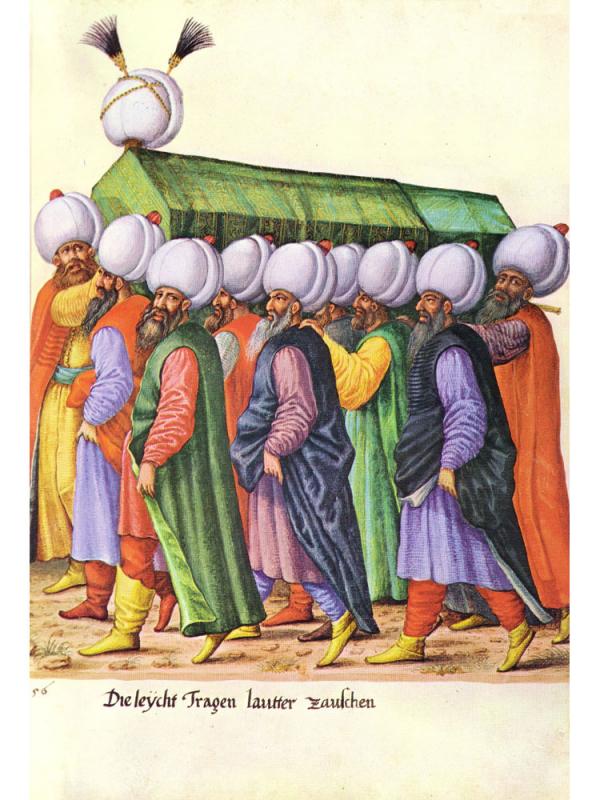

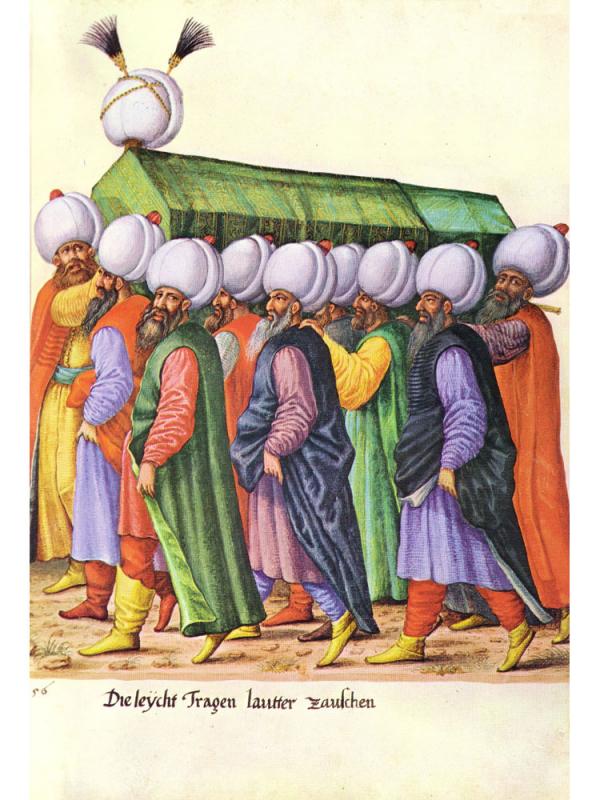

Marchers in Algiers convey a body to its grave in the 16th Century. Public ceremonies were segregated by sex. Pride of place in this man's funeral march went to his turban.

Image courtesy of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Wien, Codex 8626

Marchers in Algiers convey a body to its grave in the 16th Century. Public ceremonies were segregated by sex. Pride of place in this man's funeral march went to his turban.

Image courtesy of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Wien, Codex 8626

Antonio da Sosa, a Portuguese priest, was traveling across the Mediterranean to take up a prestigious ecclesiastical post in Sicily when a violent storm swept his ship away from the fleet. North African pirates attacked and carried their captives off to Algiers, where da Sosa spent nearly five years in the city, then under the rule of the Ottoman Turkish empire. As a theologian caught up in the confrontation between Christianity and Islam , da Sosa was not spared what he termed “Barbary cruelty.” But he was allowed to read books borrowed from other captives and from visitors to his captor’s house, and to write in his cell, and he came to know the city as he walked through it, on the way to forced labor sites. Despite his antagonism to his Muslim captors (and antipathy to their religion), he observed carefully and painstakingly recorded what he learned of their history and culture. His Topography of Algiers brings to life the sixteenth-century city situated at the crossroads of civilization with its multicultural population of Turks, Arabs, Moriscos, Berbers, Jews, corsairs, Christian captives, and Muslims. “I know everything that occurs in Algiers, and I even write it all down completely, day by day,” was da Sosa’s boast, and indeed his vibrant narrative ranges from architecture to fashion, from pirates and renegades to laborers and artisans, from festivals to government and the military, from language and currency to marriage ceremonies and funerals.

After writing about the languages commonly used in Algiers, Turkish and Arabic, da Sosa describes a lingua franca employed to address Christian captives: “It is a mixture of various Christian languages, largely Italian and Spanish words with some recently added Portuguese terms, since a great number of Portuguese captives were brought to Algiers from Tétouan and Fès after the king of Portugal, Don Sebastian, lost the battle in Morocco. . . . And what may be said about Christian languages is also pertinent to the Christian monetary system, because the escudos of Italy, France, and especially Spain are all used, as is the mithkal of Fès and the sikka of Turkey. But the foreign money that they most treasure, brag about, and benefit from are the reales of Spain, silver coins of four and eight, because they send and carry them even to Turkey and the great Cairo, and from there they move eastward to the great Oriental India, and even up to Cathay, China, and Tartary, always bringing a profit to those who carry them. And thus no merchandise is more precious, nor can anything of more worth be taken to Algiers, Barbary, or Turkey, than the reales of Spain.”

Da Sosa shared his penchant for writing with a younger fellow prisoner, Miguel de Cervantes, with whom he conversed about poetry and literature—and also about plans for escaping captivity. Ultimately, both of them fled, and from this acquaintance Da Sosa would go on to write the first biography of Cervantes. Translated by Diana de Armas Wilson and edited by Maria Antonia Garces, An Early Modern Dialogue With Islam: Antonio da Sosa’s Topography of Algiers (1612) has recently been published by the University of Notre Dame Press. The aim of the translation is, in the editors’ words, “to provide a cross-cultural understanding of North African life and customs during the era anticipating both Cervantes’s Don Quijote and Shakespeare’s Othello.” Both writers, they point out, “understood the horrific impact of religious wars on the life and times of their heroes.”