Beyond Moby Dick: Native American Whalemen in the 19th Century

A harpooning boat attacks a right whale with the larger whaling ship seen in the background.

Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-10137

A harpooning boat attacks a right whale with the larger whaling ship seen in the background.

Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-10137

In Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick (1851), Captain Ahab’s crew on the Pequod included Tashtego, “an unmixed Indian from Gay Head, the most westerly promontory of Martha's Vineyard, where there still exists the last remnant of a village of red men, which has long supplied the neighboring island of Nantucket with many of her most daring harpooneers.” Endowing Tashtego with innate hunting instincts and superior eye-sight, Melville reinforced reigning 19th-century stereotypes about Native Americans and relegated his character to the inferior role of harpooner, a “squire” to the “knights” on the ship, the boatsteerers who were petty officers.

Reality was quite different. Historical research shows that, although Native Americans in New England faced race-based oppression/limited freedom, economic exploitation, and danger at sea, the lucrative whaling economy offered them a path to paid labor and, eventually, the higher ranks on ships. From logbooks, journals, and other shipping records, Nancy Shoemaker, in her book Native American Whalemen and the World: Indigenous Encounters and the Contingency of Race (University of North Carolina Press, 2015), demonstrates that, from about 1830 on, New England natives were placed in positions of authority on a regular basis, serving as fourth, third, second, and first mates, petty officers of rising rank. And yet, prejudice and the large investment required were barriers to the highest levels: only three Native Americans became whaling masters and briefly captained ships during the 19th century.

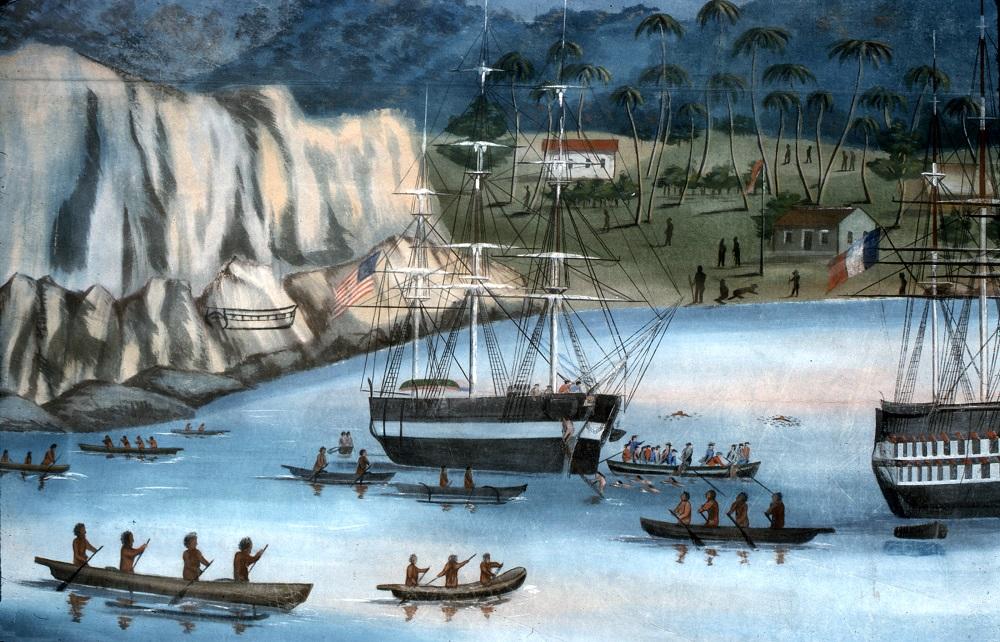

The native people of New England did not develop an independent whaling culture; they were coopted by European colonists as laborers on ships around the mid-17th century. The American whaling industry expanded rapidly from the early 1800s on and reached its apex in the 1830s-1850s. It grew into an early global enterprise, with ships embarking from Nantucket and New Bedford for the Southern Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic oceans. The descendants of the Wampanoag people, from Mashpee on Cape Cod and Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard, worked on these vessels as whalemen for generations and earned reputations as skilled and reliable crewmembers under difficult conditions.

Shoemaker’s book discusses Native Americans’ adventures and tribulations as they sailed distant oceans in search of whale prey. She explains how their own encounters with indigenous inhabitants on far-flung islands, such as Hawaii, the Marquesas, and Fiji, among others, were “fraught with ambiguity.” Native Americans who had witnessed colonial intrusion themselves now arrived together with their employers as foreign invaders and found themselves in a shifting racial middle ground. Their stories add a fascinating chapter to the complicated history of the Native American experience in an era of U.S. commercial expansion and global encounter.