100 Years Later, Mark Twain's Autobiography

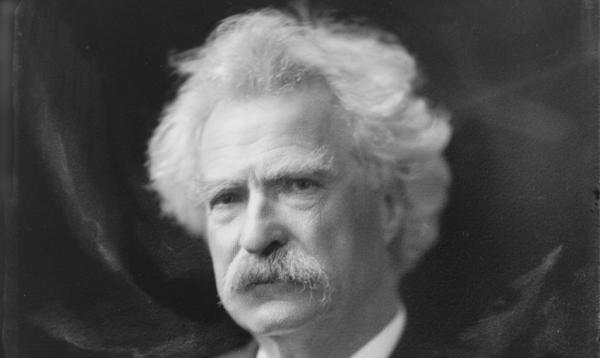

Portrait of Mark Twain

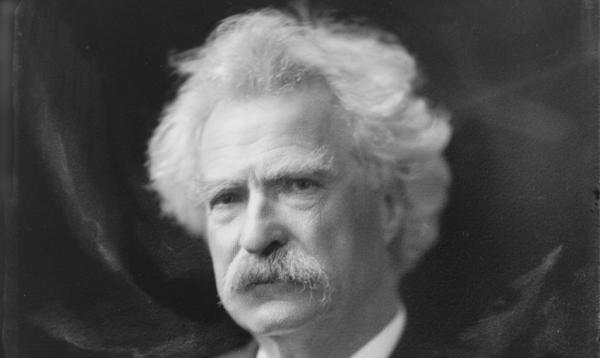

Portrait of Mark Twain

Over the course of 35 years, Mark Twain tried repeatedly to create an autobiography. His method was decidedly not chronological, swerving from one topic to the next, one time period to the next. He wrote several brief accounts of his childhood, mused on meeting General U.S. Grant in Chicago, and reflected on the beauties of the German language. Some of his efforts were only a few pages in length; others formed almost full chapters. By 1905, some thirty such “false starts” sat on the shelf in his drawing room.

In 1906, four years before his death, Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens) hired a stenographer and began a remarkable series of almost 250 daily dictations, which he collated with many of his earlier efforts. The Autobiography of Mark Twain was born. By its author’s decree, however, the world would have to wait another 100 years for its full publication.

Small selections of his amazing autobiography were published in 1924, 1940, and 1959, but Twain’s original editor, Albert Bigelow Paine, cut large sections that he found potentially damaging to the author or offensive to early 20th-century readers. In doing so, he ensured that generations of readers would come to know only the Mark Twain that Twain’s daughter and heir Clara, who died in 1962, considered appropriate.

Robert Hirst, project director of the Mark Twain Project at the University of California, Berkeley, recently told The New York Times, “Paine was a Victorian editor. He has an exaggerated sense of how dangerous some of Twain’s statements are going to be, which can extend to anything: politics, sexuality, the Bible, anything that’s just a little too radical. This goes on for a good long time, a protective attitude that is very harmful” (July 9, 2010).

Edited by Harriet Elinor Smith, the first volume of Autobiography of Mark Twain spent sixteen weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list and exists in print in over a half million copies in both traditional and electronic formats.

Supported by NEH Scholarly Editions and Translations grants dating back as far as 1979, the Mark Twain Project seeks to publish definitive editions of Twain’s fiction, letters, and journalism. To date, 37 volumes have been published under Hirst’s careful editorial eye.

The complete first volume of the autobiography, with notes and supplementary material, is available on-line, free of charge, to the general public.