The Evolution of Memorial Day

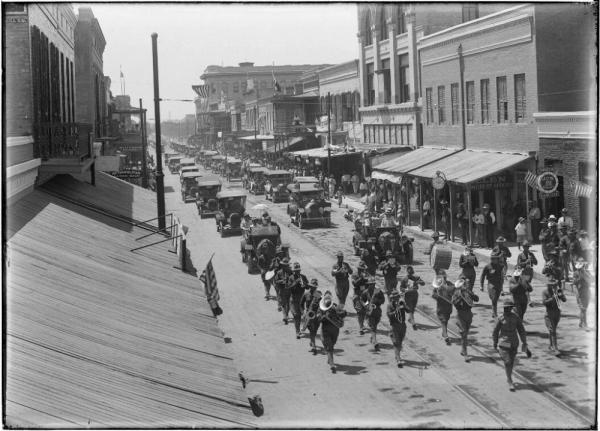

Decoration Day Parade (Brownsville, Texas), 1916.

Robert Runyon, photographer. Photo Courtesy of The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin. Runyon (Robert) Photograph Collection, RUN01326.

Decoration Day Parade (Brownsville, Texas), 1916.

Robert Runyon, photographer. Photo Courtesy of The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin. Runyon (Robert) Photograph Collection, RUN01326.

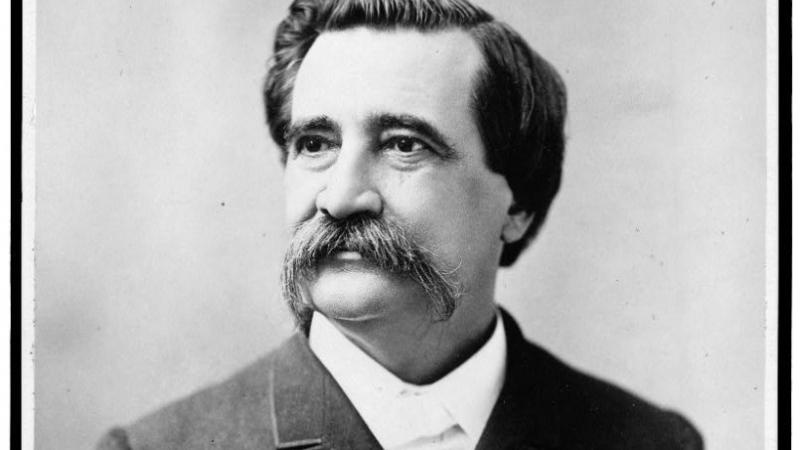

Every Memorial Day, Americans across the country recall deceased family members who served in the military by placing flowers on their graves. The origins of the May holiday go back some 150 years. By most accounts, the practice of honoring the war dead first arose in the South in the last days of the Civil War. Because of the availability of flowers, ceremonies honoring the dead were held in spring but were not restricted to any particular date. The establishment of an official day of commemoration of the war dead was the handiwork of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), an influential organization of Union veterans which at its height had nearly half a million members. The main force behind the Memorial Day campaign was John Alexander Logan (1826-1886), a former Union general and commander-in-chief of the GAR. General Logan’s official proclamation read as follows:

The 30th day of May 1868 is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the last rebellion and whose bodies now lie in almost every city village and hamlet churchyard in the land.

With the help of the GAR’s extensive network of state and local affiliates, Decoration Day, as it was first called, quickly entered the constellation of national holidays, along with the 4th of July and Washington’s birthday.

Because newspapers regularly covered Decoration Day activities, they represent a key source of information on the holiday as it evolved. A valuable aid to researchers interested in this and other historical topics is Chronicling America, an online resource consisting of more than 2,100 American newspapers, dating from 1789 to 1924. Supported by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and maintained by the Library of Congress, Chronicling America is freely available to the public. Searching the phrases “Decoration Day” or “Memorial Day” yields thousands of hits--testifying to the wide popularity of the holiday in the aftermath of the Civil War. To narrow your focus, you can also search Chronicling America by newspaper title and date, as well as by city, county, or state, thus revealing how the holiday was celebrated over time and in different parts of the country. What’s more, the Library of Congress has assembled a resource page containing links to a number of newspaper accounts of Memorial/Decoration Day, along with helpful tips for searching the database.

A good place to begin the search is the long article on the history of Decoration/Memorial Day that appeared in the May 30, 1909 edition of the Omaha Sunday Bee. This account and others underscore the key role of the GAR in staging Decoration Day events. In the early years, Decoration Day ceremonies focused exclusively on the sacrifices of Northern soldiers and sailors and underscored the righteousness of the Union’s cause. Activities were sometimes spread over several days and often included addresses by military veterans to school children, public orations, church services, and musical performances. They culminated on May 30 with a formal procession of Union veterans, dignitaries, and members of the public to the local cemetery, where participants reverently placed flowers on the graves of the war dead. The impressive scale of many of these celebrations is evident in a 1873 report from the New York Tribune, which describes the massive procession of veterans and civic groups through New York City. The combination of stirring patriotic rhetoric and poignant memories of losses of loved ones that were still fresh enhanced the holiday’s popularity and encouraged its spread. Even in smaller towns, Decoration Day became an occasion for demonstrations of civic unity and engagement. A rare note of discord was sounded on May 30, 1870, when according to the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, a group of African American marchers unceremoniously dropped out of the Decoration Day procession in that West Virginia community after being ordered to take a position “at the rear of a string of carriages, buggies, and horsemen.”

Given its association with the triumph of the Union, it is no surprise that most people in the South ignored the new holiday, holding their own memorials for the Confederate war dead at different times of the year. However, there were signs of change. A national survey of Decoration Day events that appeared in a North Dakota newspaper in 1884 noted that in Wheeling, West Virginia, both Union and Confederate veterans took part in the commemoration that year (although each group held its own separate ceremony). The same article noted that in nearby Maryland, another border state, former adversaries actually came together on May 30 for a joint celebration.

With the inevitable passing of the Civil War generation, other aspects of the holiday began to change. In 1909, the Omaha Sunday Bee reported, for example, that many of that city’s Decoration Day ceremonies had been moved indoors, “because of the advanced years of the old veterans who cannot stand the fatigue of the parade or the prolonged exercises at the parks.” Moreover, the general cessation of business activities on May 30 caused Decoration Day to take on the features of a general holiday. Newspaper reports from the 1890s, for instance, underscore the popularity of recreational activities on that day, such as bicycle races in Pittsburgh and public dances in Akron. Furthermore, with the onset of spring citizens used the opportunity to participate in outdoor activities. The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer commented in 1899 that Decoration Day had become an occasion for “picnics, outings, and other amusements,” despite the best efforts of what it called the “Grand Army boys” to uphold its original purpose.

As memories of the Civil War began to fade, so too did the sharp regional divisions that helped to inspire the formation of the holiday. The great outpouring of patriotic sentiment following the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898 did much to overcome sectional animosities. In 1902, a small Louisiana newspaper published a report of Decoration Day activities held across the United States. That year, President Theodore Roosevelt presided over the festivities in Gettysburg, paying homage to the men from the North and South alike who fought and died in the great battle 39 years earlier. The same newspaper reported that citizens in Chicago honored their former adversaries by decorating the graves of Confederates who died in a prisoner-of-war camp.

With the mass mobilization accompanying America’s entry into the World War I, Decoration Day shed once and for all its distinct association with the Civil War. Now celebrated in every part of the country, the holiday honors the contributions of all veterans, past and present. Of course, the venerable custom of “decorating” graves persists to this day, although the name of the holiday has been changed. The term “Memorial Day” had been in use as early as the 1880s and became increasingly popular after the Second World War. In 1967, an act of Congress made the new name official. A final break with the old tradition of Decoration Day followed a few years later, when Memorial Day was moved from May 30 to the last Monday in May.