Soldier Newspapers in the Civil War

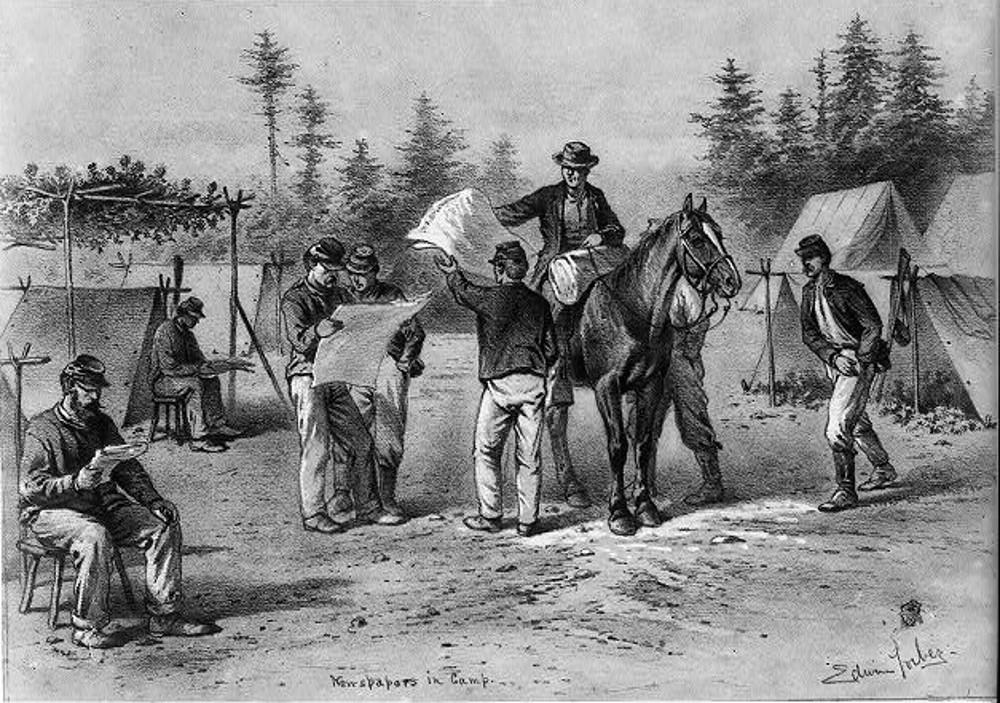

News from home, 1863. By Edwin Forbes.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.20648/

News from home, 1863. By Edwin Forbes.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.20648/

Whether based in the United States or stationed overseas, an estimated one million soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen, along with members of their families, look to Stars and Stripes for information about the world. Currently available in both print and digital editions, Stars and Stripes has appeared continuously since the Second World War.

But the first newspapers produced by and for members of the U.S. armed forces began many years earlier, during the Civil War. The original Stars and Stripes newspaper debuted in November 1861, thanks to the efforts of troops under the command of General Ulysses S. Grant. Separated from the usual channels of information and seeking news about the fighting breaking out around them, men from the 18th and 29th Illinois Volunteers based in Bloomfield, Missouri, seized a local newspaper and adapted it for their own use. They called their publication Stars and Stripes, and it was one of a number of similar papers created for Union soldiers during the war years. Others include the Union Guidon, Camp Kettle, and Unconditional S. Grant.

Thanks to the National Endowment for the Humanities’ National Digital Newspaper Program, several Civil War-era soldier newspapers have been digitized, along with more than 2,000 other American newspapers from the period 1836 to 1922. All are freely available at Chronicling America, an online resource maintained by the Library of Congress. In addition to perusing the newspapers themselves, you can also consult essays containing interesting background information about each of the titles. Below are examples of military newspapers from the Civil War period you can access through Chronicling America.

The Shenandoah Valley town of Martinsburg, West Virginia, changed hands more than thirty times in the course of the conflict. Union forces occupied Martinsburg in the summer of 1861. As Independence Day approached, the troops’ patriotic sentiments were kindled, inspiring a dozen volunteers from the 2nd Pennsylvania Infantry to launch a newspaper they called the American Union. Leading the effort was Captain William B. Sipes, who had edited a newspaper in his home town of Pottsville, Pennsylvania, before the war. The American Union consisted of four pages of official announcements and reports of nearby military actions, as well as patriotic songs and poems intended to promote the morale of the troops. Although its very title was intended to convey antipathy toward secession, hopes for reconciliation with the South remained strong. In a section dedicated “To the People of Virginia,” the American Union assured its readers that the sole intent of the occupiers was to “reestablish peace and order.” Shortly thereafter, Sipes’ regiment left Martinsburg, however, bringing the American Union to an abrupt end.

The constant movement of troops, together with the perennial shortage of paper for print, meant that most Civil War military publications were destined to be short-lived. This was certainly true for the Winchester Army Bulletin, founded in the summer of 1863 by soldiers of the Army of the Cumberland while occupying the town of Winchester in central Tennessee. After confiscating the press of a virulently anti-Northern newspaper whose editor had fled the state, the troops turned the Bulletin into a conduit for official army notices as well as a source of updates on the fighting. Being situated in enemy territory, army newspapers could not reasonably expect to garner advertising support. The Winchester Army Bulletin was a rare exception; one H.A. Huntington posted an ad placed for an “Officer’s Outfitting Emporium.” In July 1863, the Bulletin celebrated the great Union victory at Vicksburg, but despite its triumphant mood, the editor admonished “foraging” Union troops to avoid committing depredations against civilians. In an equally conciliatory manner, the Bulletin urged “the ladies [of Winchester]” to “soften their asperity and dislike for our ‘yankee officers,’ as they call them…” who were, the paper took pains to point out, truly “congenial fellows--gentlemen of the nobler sort.” After only a few months, the Army of the Cumberland pressed deeper into Southern territory, and the Winchester Army Bulletin ceased its operations. Two of the men associated with the paper later went on to establish the Chattanooga Army Bulletin.

Early in the war, the North took advantage of its overwhelming naval superiority to seize large portions of the Confederacy’s coastline. Union troops stationed in and around the occupied town of Port Royal, South Carolina, looked to an army publication known as the Palmetto Herald for news of the war. Its founder, Samuel Mason, had formerly worked for a Boston newspaper. Mason described the Herald as “a journal of notable events in the [U.S. Army’s] Department of the South.” Its coverage included news items from other Union-occupied ports and reports drawn from various Northern newspapers. The Palmetto Herald ran for 10 months, considerably longer than most soldier newspapers. The final issue appeared in December 1864, after which Mason moved his operations to Savannah, Georgia.

Exceptionally long-lived by the standards of Civil War military publications was another Port Royal journal called the New South. Boston native, Joseph Henry Sears, an army captain and postmaster, had first launched the newspaper in March 1861, shortly after Union forces took control of the area. Sears observed that although “Issued in a military command [and], addressed mostly to soldiers at the seat of war the audience [for the New South] is yet not purely military.” In fact, the New South developed an unusually large following. At the height of its popularity, nearly 10,000 copies were in circulation, and its stories relating to the war effort were picked up by newspapers throughout the North. When the war ended, the New South transferred its operations to nearby Beaufort where it continued for another year or so.

Also worthy of mention is the Soldier’s Journal. This paper was not founded by soldiers as such, but instead by Amy Morris Bradley, a volunteer nurse formerly attached to the 5th Maine Infantry who went on to serve as an administrator in the U.S. Sanitary Commission. In February 1864, when the Union hospital camp situated in Alexandria, Virginia--just across the river from Washington, D.C.--was converted into a station for troops awaiting deployment to the South, Bradley was inspired to organize the Soldier’s Journal. Like other papers of its kind, it published reports on battles and letters from soldiers, as well as providing information about hospitals and the availability of supplies. Active for the remainder of the war, the Soldier’s Journal had a phenomenal 20,000 subscribers, among the most eminent of which were Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant.

Once the Civil War came to an end, most of the soldier newspapers were quickly forgotten. Short print runs for most of these titles contributed to their general obscurity. (Only a single issue of the original Stars and Stripes, for example, appears to have survived.) And yet, the existence of these newspapers testifies to the unusual resourcefulness of soldier-journalists for whom neither the terrors of the battlefield nor the tedium of camp life could stay their desire for information.