Chronicling America Dispatches: “Published for the elevation of our race”: Ten historical African American South Carolina newspapers in Chronicling America

African American Newspapers

Courtesy Virginia Pierce

African American Newspapers

Courtesy Virginia Pierce

From time to time, we like to highlight dispatches from our state partners participating in the National Digital Newspaper Program, a joint sponsorship between the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Library of Congress to create a national, digital resource of historically significant newspapers published between 1836 and 1922, from all states and U.S. territories. The following dispatch comes from our South Carolina state partner, the University of South Carolina Libraries.

Much has been written about the African American experience, but there are few primary resources written from an African American perspective that are as rich in content, and as freely accessible, as the almost fifty historic African American newspapers now available in Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. During its recent participation in the National Digital Newspaper Program, the South Carolina Digital Newspaper Program (SCDNP) had an opportunity to contribute ten 19th- and early 20th-century African American newspapers published in South Carolina to the growing selection of digitized historical African American newspapers in Chronicling America.

The inclusion of these African American newspapers from South Carolina was only possible through the much earlier efforts of the forward-thinking American Council of Learned Societies’ Committee on Negro Studies. This committee assembled the incomparable Negro Newspapers on Microfilm collection in the 1940s in an endeavor to preserve African American primary sources for future study.[i] In doing so, they successfully created a cohesive microfilm collection of more than two hundred 19th-and early 20th-century African American newspapers whose surviving printed issues were dispersed among hundreds of repositories across the United States.[ii] Since only a small number of African American newspapers published in South Carolina prior to 1922 are known to have survived, and only a few original issues of those are currently held in South Carolina repositories, SCDNP was keen to work with the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the Library of Congress to access the South Carolina content from the Negro Newspapers on Microfilm and make it more widely available. [iii]

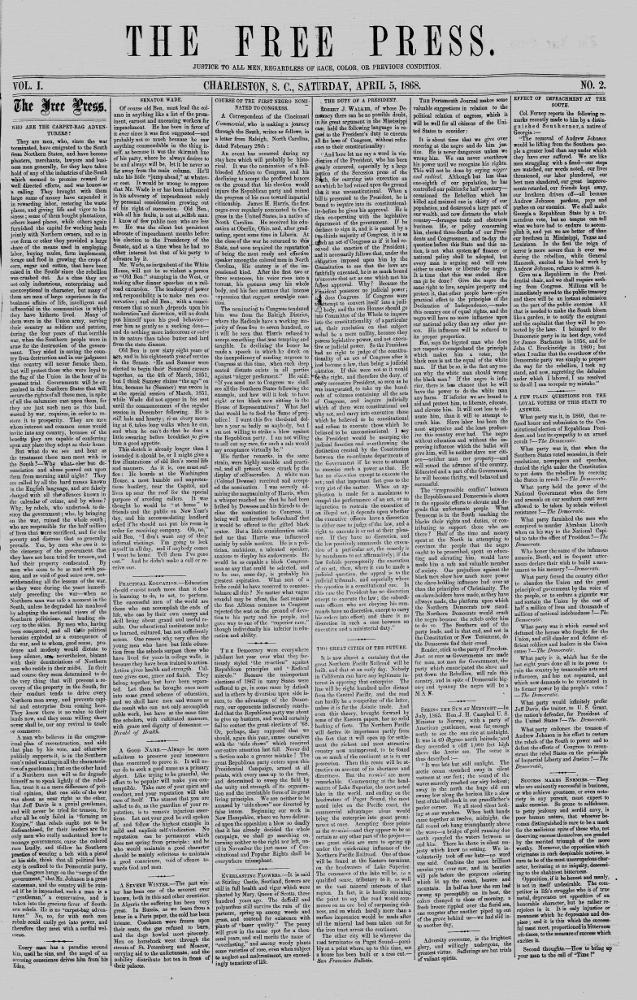

The ten African American newspapers from South Carolina now accessible through Chronicling America were published between the years 1865 and 1922 during two distinct periods in the state’s history. Six of the newspapers were published between 1865 and 1876 in the tumultuous Reconstruction period, sometimes regarded as the second half of the Civil War in South Carolina. The papers published during this era are Charleston’s South Carolina Leader, Charleston Advocate, Missionary Record, Free Press and the Georgetown Planet and the Orangeburg Free Citizen. They covered news and events from an African American perspective in contrast to the often biased representation of black South Carolinians in newspapers published by their white contemporaries. They are also insightful resources in the details of community life, such as the activities of churches, schools, and fraternal organizations that African Americans created as freed people. For example, in October 1865, the South Carolina Leader contemplated freedom as the normal condition of man and shared another moving article on the “Duties of the Hour” that freedmen were called upon to undertake. In December 1865, when Congress passed the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery, the South Carolina General Assembly soon passed “black codes” to maintain strict control over the activities of African Americans. The South Carolina Leader defended the interests of blacks in pieces like “Loyalty and the Planters,” “To Make Good Citizens of Freedmen,” and “South Carolina’s New Laws.” Glimpses of the recently emancipated freed people’s treatment by their former masters and the difficulty the Freedman’s Bureau and occupying Federal Troops had in enforcing their protection are evident in small pieces like “Expulsion of Freedmen.”

The 14th Amendment passed in 1868 offered citizenship and equal protection under the law to all persons born in the United States, and the 15th amendment in 1870 granted African American males the right to vote. The new black majority in states like South Carolina was able to elect African Americans to positions of political power at both the local and national level. An article in Charleston’s Free Press considered the “Course of the First Negro Nominated to Congress.” Men like Richard Harvey Cain (1825-1887), publisher of the Missionary Record, seized the opportunity to advocate for racial equality, women’s suffrage, compulsory education, and opportunities for property ownership.[iv] Cain also pushed strongly for school integration in the Civil Rights Act of 1875. As a Congressman, Cain advised whites not to discount the contributions that African Americans had already made to the southern economy as an essential labor force, noting the many skilled and capable tradesmen who had built the infrastructure of the South.

Like many other educated freeborn African Americans from the North, Cain came to South Carolina in 1865 to improve conditions of newly freed slaves. Serving as minister of Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, Cain and other newspapermen placed themselves on the front lines of social change, pushing for educational opportunity and fair labor contracts for more vulnerable African Americans. Cain’s daughter later recalled that her family “lived in constant fear at all times.”[v] Their concerns were not unfounded as violence against African Americans escalated during this period.

One prominent example is the murder of South Carolina State Senator Benjamin Franklin Randolph (1820-1868) by white assassins.[vi] Randolph, an educated minister born free in Kentucky, served as Chaplain to the U.S. Colored Troops Regiment on Hilton Head Island and remained in South Carolina after the war as a member of the American Missionary Association and the Freedmen’s Bureau. Randolph quickly became immersed in South Carolina politics and served as an associate editor for the Charleston Advocate in 1867-68. The white newspaper, the Orangeburg News, published a disparaging account of Randolph. For a more sympathetic portrait of Randolph’s activities, see “Assassination in Our State” in the Charleston Advocate.

Other missionaries and ministers who came to South Carolina in these years were Timothy Willard Lewis and Alonzo Webster, who established the Charleston Advocate and taught at new African American educational institutions in the state.[vii] In 1869, Lewis and Webster also founded a Methodist institution called Claflin University which is still in existence today as a historically African American college. Around this time, Alonzo Webster and his son Eugene also established the Free Citizen.[viii] Alonzo Jacob Ransier (1834-1882), associated with the Missionary Record, was a freeborn person of color from Charleston.[ix] In addition to serving locally in numerous political capacities, Ransier, like Richard Harvey Cain, was one of twenty African Americans elected to the U.S. House of Representatives during Reconstruction. Ransier was especially known for his eloquent defense of the Civil Rights Bill.

African American newspapers like the Charleston Advocate, Free Press, and Georgetown Planet were short lived because of many obstacles faced during these years. When Federal troops and the Freedmen’s Bureau withdrew from the state in the 1870s, white South Carolinians fought against black participation in government and once reasserted political control by 1877. As Reconstruction drew to a close, most of the early African American newspapers in South Carolina folded.

Four additional African American newspapers were active in South Carolina between 1898 and 1922. These were the “Jim Crow” years when southern whites had cemented political and social control and intensified their efforts to disenfranchise blacks. This era in South Carolina was characterized by changes in state and federal laws. The revision of the state constitution in 1895 which established Jim Crow laws and the U.S. Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson 1896 ruling which established the “separate but equal” rule exemplify the country’s about-face in terms of African American civil rights. Resisting these efforts in South Carolina were the Charleston Afro-American Citizen, Rock Hill Messenger, and Columbia’s People’s Recorder and Southern Indicator.

Additionally, African American communities throughout the South were terrorized by lawlessness and unprosecuted lynchings which spiked in the 1890s.[x] This was one catalyst for the Great Migration when tens of thousands of African Americans left the South. In 1921, the Southern Indicator published an article titled “The Fight for a Federal Anti-Lynching Bill,” describing efforts of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People on behalf of the legislation. Despite persecution, many African Americans succeeded in creating better conditions and opportunities for themselves and their communities. Individuals like Modjeska Simkins who helped found Victory Savings Bank in 1921, one of the earliest African American owned banks in the United States, was one of many community leaders who helped black South Carolinians “make a way out of no way.”[xi]

In the face of discrimination, African American newspapers espoused positivity and endorsed upward mobility. They commonly used phrases like “justice for all men,” “dedicated most especially to the struggling but rising Afro-Americans,” or “published for the elevation of our race.” Many invoked the golden rule in their mottoes. One of the editors of this time, Louis George Gregory (1874-1951), a native South Carolinian and the son of former slaves, epitomized this spirit of possibility. Gregory edited the Afro-American Citizen in Charleston between earning degrees at Fisk University and Howard School of Law.[xii] Gregory is best known for his adoption of the Baha’i faith which he saw as key to establishing racial harmony in America.

The presence of these newspapers provides evidence of new opportunities for an emerging middle class of African Americans in urban areas of the state. For example, between 1898 and 1922 the People’s Recorder and the Southern Indicator in Columbia contained ads for nearly 175 individual African American businesses. They included physicians, dentists, attorneys, and other skilled tradespeople, an indicator of a growing professional class of African Americans in the segregated city. Captain Philip Thomas White, a native of South Carolina and educator at two African American schools, established the Rock Hill Messenger in 1896. Although only one issue of the paper (from 1900) exists, the Messenger was thought to have been published for 25 years until 1921. Similarly, only a single 1900 issue is known to exist for Charleston’s Afro-American Citizen. Nonetheless, both newspapers provide considerable insight into activities by African Americans in two different regions of South Carolina at the turn of the 20th century. Coverage included state and national politics, activities of African American and educational institutes such as the Friendship Institute in Rock Hill or the Lancaster Normal and Industrial School, and organizations like the Y.M.C.A., the African Protective League, and Jenkins Colored Orphanage in Charleston. Other potent articles can be found in these two turn-of-the-century papers on the evils of lynching, the broken state of politics in a piece titled “As We Predicted,” and in the ambiguities of race titled “The Other Side.”

Historian Robert L. Harris has noted that work of the ACLS’ Committee on Negro Studies to collect and preserve 19th-and early 20th -century African American newspapers “was singularly important because it brought a resource to the foreground that scholars could use to investigate the life and thought of Afro-Americans.”[xiii] By contributing to the growing selection of digitized historical African American newspapers in Chronicling America, the NEH, Library of Congress, and in small part the SCDNP, are making these irreplaceable historical resources more accessible than ever to researchers. As more and more scholars and educators learn that they can access these African American newspapers in Chronicling America, it will undoubtedly further enhance our understanding of African American history and provide a more comprehensive and nuanced history of both America and South Carolina.

[i] In Segregation and Scholarship: The American Council of Learned Societies’ Committee on Negro Studies: 1941-1950, Robert L. Harris credits Dr. Lawrence D. Reddick, Curator of the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Collection for proposing the ambitious project to assemble and microfilm 19th- century black newspapers. The Committee on Negro Studies surveyed more than 300 repositories and private collections throughout the country and worked with the Library of Congress to microfilm the original newspapers into a cohesive collection of 140,000 newspaper pages. Harris, R. (1982). Segregation and scholarship: The American Council of Learned Societies’ Committee on Negro Studies, 1941-1950. Journal of Black Studies, 12(3), 315-331. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2784250.

[ii] In 1947, Armistead Pride wrote a brief account of the Committee on Negro Studies’ microfilming project titled Negro newspaper files and their microfilming. Pride, A.S. (1947). Negro newspaper files and their microfilming. Journalism Quarterly, 24, 131-134. And Hamilton, D. (1972). A guide to Negro newspapers on microfilm: A selected list. Retrieved from ERIC, http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED062240. ED062240.

[iii] SCDNP ordered duplicate negative microfilm directly from the Library of Congress to obtain the South Carolina content of the Negro Newspapers on Microfilm collection and was also able to obtain duplicate negative microfilm of one 19th- century African American newspaper from South Carolina held by the New York Historical Society.

[iv] United States House of Representatives (n.d.). Cain, Richard Harvey. United States House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. Retrieved online.

[v] United States House of Representatives (n.d.). Cain, Richard Harvey. United States House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. Retrieved online.

[vi] B.F. Randolph (1820-1868). (n.d.). Burke, W. L. (Ed.), “All we ask is equal rights” African-American Congressmen, Judges & Lawmakers in South Carolina. Retrieved from the University of South Carolina School of Law online.

[vii] Library of Congress. (n.d.) Essay on The Charleston advocate in Chronicling America: Historic American newspapers. Retrieved online.

[viii] Library of Congress. (n.d.) Essay on The free citizen in Chronicling America: Historic American newspapers. Retrieved online.

[ix] Alonzo J. Ransier. (2006). J.C. Smith (Ed.), Notable Black American Men, Book II (Vol. 2). Retrieved from Biography in Context at http://ic.galegroup.com.

[x] In their 2015 report, Lynching in America: Confronting the legacy of racial terror, the Equal Justice Initiative’s new research demonstrates that a spike in lynchings occurred across all southern states in the 1890s (Figure 1, p. 41). Their detailed research also concluded that over 4,000 African Americans were lynched in southern states between 1877 and 1950 (Table 1, p. 40). Equal Justice Initiative (2nd edition, 2015). Lynching in America confronting the legacy of racial terror. Montgomery, Alabama: Author.

[xi] Actively working to establish this bank was an early accomplishment of Modjeska Simkins’ (1899-1992) during her long life of dedicated service to uplifting and improving the lives of her fellow African American South Carolinians. Victory Savings Bank, founded in 1921 and carefully managed by Simkins and others, remains one of the longest running and oldest African-American owned banks in the country. University of South Carolina South Carolina Political Collections (n.d.). Modjeska Monteith Simkins (1899-1992) Papers, 1909-1992 finding aid. Retrieved online.

[xii] Morrison, G. (2009). Gregory, Louis George (1874-1951). The Baha’i Encyclopedia Project online. Retrieved online. Also Morrison, G. (1982). To move the world: Louis G. Gregory and the advancement of racial unity in America. Wilmette, Illinois: Baha’i Publishing Trust.

[xiii] This was especially true because at that time African American Studies was a relatively new field of study. Robert L. Harris believed that up to that point, around the mid-20th century, many white scholars had ignored the role of black people in American society and had not included or searched for “black opinion on the assumption that little evidence existed.” Harris, R. (1982). Segregation and scholarship: The American Council of Learned Societies’ Committee on Negro Studies, 1941-1950. Journal of Black Studies, 12(3), 315-331.

Virginia Pierce is a Reference Librarian and Assistant Professor at Francis Marion University in Mars Bluff near Florence, S.C. She served most recently as the former South Carolina Digital Newspaper Project Manager at the University of South Carolina Libraries in Columbia, S.C.