Agricultural Literature and Rural Life

Photograph of a man plowing a field in Colorado using a mass-produced plow pulled by a team of horses.

University Historic Photograph Collection, Colorado State University, Archives and Special Collections.

Photograph of a man plowing a field in Colorado using a mass-produced plow pulled by a team of horses.

University Historic Photograph Collection, Colorado State University, Archives and Special Collections.

“Agriculture . . . is our wisest pursuit, because it will in the end contribute most to real wealth, good morals and happiness” —Thomas Jefferson, letter to George Washington from Paris, 14 August 1787

We may not need a quote from a founding father to know the importance of agriculture, but a full understanding of the history of the United States requires an appreciation of our rural heritage. From the arrival of the first Native Americans to the many subsequent waves of settlers and immigrants, agricultural work has transformed the American countryside. Not only has the sowing of crops shaped our landscape and environment, it has also influenced many aspects of American society. It is easy to forget in our urban culture that as recently as 1870, more than 70 percent of Americans worked the land. For most of U.S. history, the farm has been the foundation for family life in America. Most rural communities and many cities depended on agricultural production for their livelihood. Throughout American history agricultural activity has been the engine that spurred land ownership, maintained state and local economies, motivated pioneers and family farmers, and produced our “amber waves of grain.”

Preserving the Legacy

A significant record of the history of agriculture in America can be found in documentary and literary collections of research libraries at land-grant universities across the country. These materials included resources ranging from the memoirs and transactions of early agriculture societies to newspapers and almanacs; family, community, and corporate archives; and state and county extension service publications. A complementary body of published materials included agricultural periodicals that chronicled farm life and economy, as well as the many local, regional, and national farm journals that exhorted, informed, and shaped the opinions, values, and concerns of early farm families. Unfortunately, most printed materials created after 1840 were on acidic paper that rapidly broke down. By the 1980s, much of this literature was in danger of crumbling to dust on library shelves, which would have meant the loss of records on many aspects of rural history.

To preserve this literature and to increase future access to it, the Mann Library at Cornell, in collaboration with the United States Agriculture Information Network (USAIN), coordinated the work of librarians, preservationists, and researchers concerned with the survival of these collections. Beginning in 1993, USAIN began the systematic review and planning for the preservation microfilming of agricultural materials held in the research collections of major land-grant universities. In 1996, Cornell University applied to the National Endowment for the Humanities for support to undertake the project. Over the period from 1996 to 2008, the consortium received six grants totaling nearly $4.5 million.

The effort was based in part on the bibliographic work of librarian Wallace Olsen at Cornell who formulated selection criteria for materials to be preserved and who coordinated teams of scholars to review the massive bibliographies of agricultural literature produced in each state. Olsen’s own bibliographic work was published in the seven-volume Literature of the Agricultural Sciences (1991–1996), which provided a basis for the selection of materials digitized through the Core Historical Literature of Agriculture (CHLA), a project begun at Cornell in 1994. CHLA has digitized agricultural materials of national significance and currently provides public access to over 1 million pages scanned from more than 2,000 books and 26 journals. Olsen’s bibliographic work and CHLA proved to be one step in the larger effort, subsequently funded by NEH, to preserve the large body of state and local agricultural articles, journals, and outreach publications produced or held by land-grant universities across the country. Following planning efforts to create a nationwide strategy to preserve historical agricultural literature in the early 1990s, the USAIN advisory panel on preservation produced the National Preservation Program for Agricultural Literature in 1993, which served as a guiding document for coordinating preservation efforts across agricultural collections. Together USAIN and Cornell, with coordination by Olsen who served as the first project director, applied to NEH for support to put the preservation plan into action.

The project first sought to produce bibliographies of agricultural literature in each state. General ranking schemes based on key topic areas and preservation need were used by every collection, and individual state universities participating in the project also developed local priorities, based on the agricultural history of each state, for selecting materials related to agriculture and rural life that would be microfilmed or digitized. In all, agricultural bibliographies were completed for twenty-nine states. The amount of available literature on the history of agriculture is enormous. Colorado for example, identified 4,000 print items and 12,000 additional archival materials (numbering nearly 75,000 individual pages preserved); the University of Kentucky’s bibliography contained 12,498 items, with 6,455 prioritized for further preservation attention; South Dakota State University submitted a bibliography of nearly 2,000 items, excluding a large portion of materials published by the university’s Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension. In the final analysis, NEH funding supported bibliographic analysis, selection, and preservation microfilming of nearly 34,000 volumes, as well as the digitization of over 141,000 pages, of agricultural literature published between 1820 and 1945.

The NEH project sowed the seeds for further development of these collections. Although many of the items remain accessible only in their microfilm versions, which are held at the original libraries and at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Library, many of the individual libraries (for example, in Colorado and Arizona) have created digital collections of these materials.

Historical Agricultural Literature

The stories of American agriculture are told through a broad swath of primary sources, both published and unpublished, many of which are now preserved on microfilm or available on the Web. Many of these materials date to the nineteenth century, a period when agriculture experienced an unprecedented growth in productivity. Farming and agricultural communities also changed greatly during this time. In 1820, farming was a self-sufficient enterprise largely unchanged since colonial times; by the beginning of the twentieth century, farming was no longer oriented to local communities and families but was directed instead to larger markets and expanding urban populations. These changes were furthered in part by the proliferation of agricultural literature produced by individual horticulturalists and farmers, researchers and engineers at land-grant universities, and agricultural manufacturers, all of which served as a means of sharing and expanding agricultural knowledge. One might say that these publications were as important to the agricultural economy of the nineteenth century as social media and the Internet are to the information economy today.

Manuals and advertisements discussing new types of crops, farm management techniques, and other vehicles for improvement formed a large part of this literature. Trade journals and agricultural publications supported the introduction of new crops and livestock. Notable activity was devoted, for example, to beekeeping, as evidenced by Englishman Thomas Nutt’s 1832 monograph, Humanity to honey bees, or, Practical directions for the management of honey bees upon an improved and humane plan, by which the lives of bees may be preserved, and abundance of honey of a superior quality may be obtained. Nutt proposed his own designs for bee houses, which he promised would lead to higher amounts of honey production, so long as readers followed his advice to the letter. In his words, “I do flatter myself that the principle of managing Bees after my plan is right.” That Nutt’s publication was available in the United States suggests a close relationship between American and European agriculture in the early nineteenth century. By 1879, an American publication rivaled Nutt’s both in the length of its title and advice for beekeepers: A. I. Root’s The A B C of bee culture: a cyclopædia of everything pertaining to the care of the honey bee, bees, honey, hives, implements, honey plants, &c., &c.: compiled from facts gleaned from the experience of thousands of bee-keepers, all over our land, and afterward verified by practical work in our own apiary (Medina, OH, 1879).

The expansion of agricultural literature mirrored the advances in applied science that helped to foster more specialization and greater productivity in farming. Beginning in the 1840s, many journals featured columns with titles like “Cattle Husbandry,” “Horticulture,” and “Poultry.” Educational and engineering advances led to the proliferation of new production and distribution techniques. In particular, the foundation of the land-grant university system through the Morrill Act of 1862 paved the way for rapid growth in applied agricultural research and led to the creation of a body of specialized scientific literature on farming that was circulated among rural communities throughout the United States. Although most activities of these institutions went toward agricultural research and engineering, many efforts also supported general education about agricultural work, whether for lifelong learners at extension campuses or to primary-school learners through organizations like 4H. For example, Alice McCloskey’s “Poultry” entry for the May 1905 issue of Boys and Girls magazine (“official organ of the Chautauqua junior naturalist clubs”), gives pointers on identification, care, and feeding. McCloskey advises youthful readers to observe differences between various breeds, noting, “I am sure you will not see two hens alike any more than I should expect to find in your schoolroom two boys or girls exactly alike.”

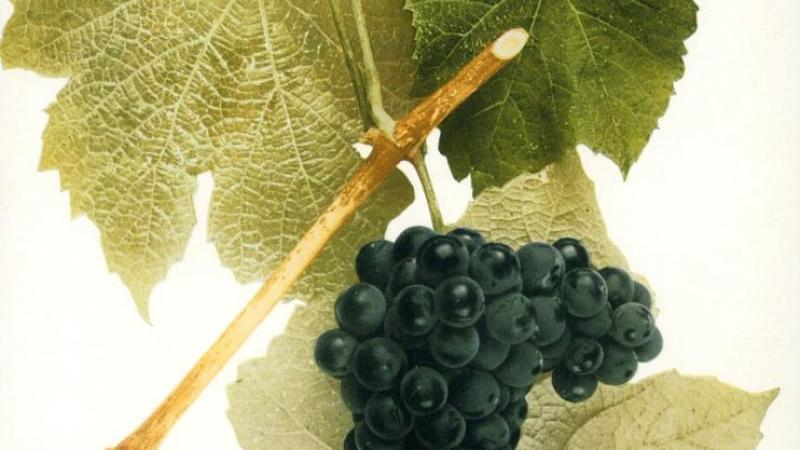

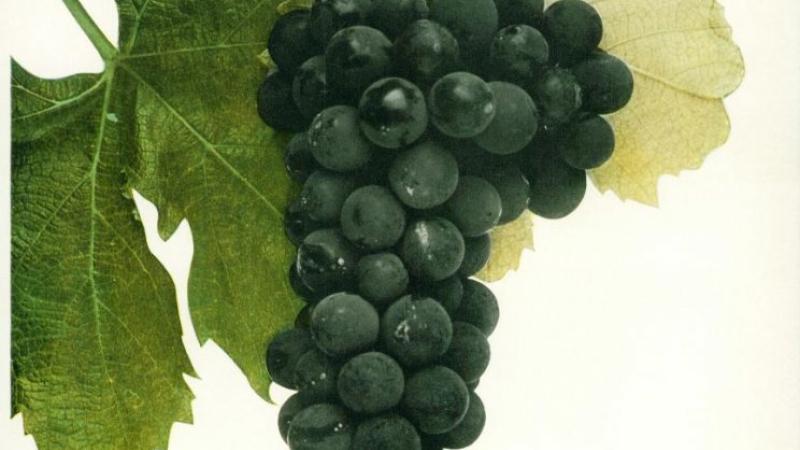

Other examples of agricultural literature preserved through this project deal with the many concerns of running a farm, such as how to store produce before it is brought to market. For those unfamiliar with the latest trends in barn construction, William A. Radford composed Radford’s combined house and barn plan book, being a complete collection of practical, economical and common sense plans of houses, barns, outbuildings, stock sheds, etc, illustrated with over twelve hundred copper half tone plates and zinc etchings, and containing over three hundred house and barn designs (Chicago, 1865). The development of new cultivars in farms and gardens increased the variety of produce available in markets. For example, the manual All about Peas by W. T. Hutchins (Philadelphia, 1892) notifies gardeners of new varieties of sweet peas available for purchase and advises on their successful cultivation. Accompanying illustrations, such as that for “The Senator” variety, entice readers with the prospect of lush summer harvests. Similarly, James J. H. Gregory introduces readers to the finer points of cabbage cultivation and marketing in his Cabbages and Cauliflowers: How to Grow Them, a practical treatise, giving full details on every point, including keeping and marketing the crop (Boston, 1889). Particularly notable for its beautiful color-plate illustrations is The Grapes of New York (Albany, 1908), which lists hundreds of varieties of grapes, many created in the United States such as the “America,” which would be of interest or suitable for cultivation in the soils and climate of New York. Another attractive variety that had nearly disappeared by the early twentieth century, is the “Black Eagle,” which according to the authors, “has wholly failed as a commercial variety and its several weaknesses will prevent amateurs from growing it largely, yet it is far too good a grape to give up altogether and lovers of grapes should keep it in cultivation.”