Humanities' secret mission: creating safe places to talk

Overflow crowd at Colorado Humanities' High Plains Chautauqua

Colorado Humanities

Overflow crowd at Colorado Humanities' High Plains Chautauqua

Colorado Humanities

"The trick is getting people from both sides of the aisle together," bemoaned a young program officer at a recent meeting, when we were discussing the shift from Chautauqua and lecture-format programming to conversation-format programs.

"Our Chautauqua programs do just that," I replied. "Our most successful Chautauqua Festival, High Plains in Weld County, attracts 7,000 people a week in one of our more conservative areas of the state." Last year our Program Committee Chair Dr. Ron Edgerton led the white, older, educated, middle class audience in singing Woody Guthrie's a labor protest song, "Union Girl."

My first experience of Chautauqua in Colorado was Charles Pace portraying Malcolm X at the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library in the Five Points neighborhood of downtown Denver. After the presentation, three young men in gang regalia spoke with Charles about what Malcolm might have thought of gangs today. They wouldn't’t have come to a lecture on Malcolm or to a conversation about "Race in America." They came to meet the man.

Colorado Humanities hosted the Maryland Humanities Council-designed “Martin & Malcolm” conversation with Charles Pace and Bill Grimmette at the New Hope Baptist Church in Denver. At the Q & A people lined up to talk with the Civil Rights leaders, with Martin and Malcolm. The hour-long conversation started in the past but quickly moved to the present, running far beyond the scheduled time. People were still lined up to talk. This strange, seemingly anachronistic form of edutainment gives non-reading and reading audiences a chance to talk with our foremothers and our forefathers. It delivers history in person and truly brings it alive.

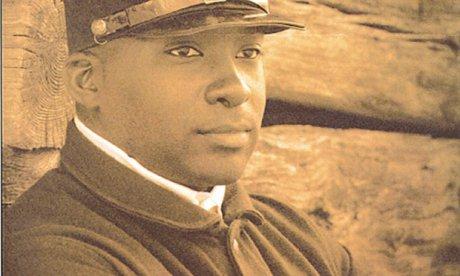

Colorado Humanities' Black History Live tour included Hasan Davis in the role of Angus August Burleigh, a black Union soldier in the Civil War. Davis is Deputy Commissioner of Kentucky Juvenile Justice. The development of his role was supported by the Kentucky Humanities Council. If Chautauqua gives members of the audience the chance to meet history in a personal manner, it also provides the performer a rich experience of giving to the community. Davis speaks eloquently about why he does Chautauqua.

The shared study of all the humanities disciplines builds bridges across aisles that have worn into chasms. "It’s the secret mission of all our programming," I told Edie Manza during Colorado Humanities' recent self-assessment and review site visit. “We create safe places for difficult conversations.”

I have driven old black Saabs over the mountains for humanities councils in the West since 1990, first as a discussion leader for Idaho’s "Let’s Talk About It." I remember rolling into a small town in southeastern Idaho where the locals were having a dispute about land use—imagine that! I walked into a room divided by an aisle and those on the right side of the aisle were not talking to those on the left. I don’t remember the text. I hope it was Walden. These folks thought they had only one topic to talk about, but once they realized they were in a safe, moderated book discussion, they just wanted to talk. They wouldn't stop. One participant told me afterward that "we never would have talked like that if we hadn't had a visiting scholar we trusted moderate the conversation." But I knew that, because they had all read the same book and had come to talk about that, they did indeed have common ground for a conversation. The discussion about the book made them feel safe enough to move on to the conversation they needed to have, even though it included their differences and difficulties.

Josephine Jones is the author of Sane in Pain: Create Your Pain Management Plan forthcoming soon from Rainy Day Women Press and a former Idaho Literary Fellow. She directs programs and the Colorado Center for the Book for Colorado Humanities.