Shakespeare in a Divided America: A Q&A with NEH Public Scholar James Shapiro

James Shapiro

Courtesy of James Shapiro, Photo: Mary Cregan

James Shapiro

Courtesy of James Shapiro, Photo: Mary Cregan

What can William Shakespeare (1564-1616), a centuries-old English playwright and poet who never set foot in the New World, tell us about our America? Quite a lot, it seems, according to NEH Public Scholar James Shapiro. In his new book, Shakespeare in a Divided America, Shapiro investigates eight important episodes in American history and the ways that Shakespeare’s work was invoked within each of them. As Shapiro writes, “For well over two centuries, Americans of all stripes—presidents and activists, writers and soldiers—have […] turned to Shakespeare’s works to give voice to what could not readily or otherwise be said.” I spoke with Shapiro to get a better understanding of the unique connection between the Bard and the American experience.

Why exactly is Shakespeare’s art so applicable to American politics and history? What accounts for that malleability?

America is a relatively young country, one that has struggled over the decades and centuries with unresolved issues ranging from race, empire, and assassination, to immigration, inclusion, and gender. Many of Shakespeare’s plays turn on these issues—whether it is crossdressing in the comedies or the killing of political leaders in the tragedies—so it’s hardly surprising that Americans would find in them a roadmap to working through their own convictions and differences.

In the opening chapters, you talk about John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy Adams, and Abraham Lincoln, and many other presidents, all of whom turned to Shakespeare in some way. Is there some organic connection between the American presidency and Shakespeare’s work?

The Founding Fathers and early presidents were steeped in Shakespeare. John Adams and Jefferson made a pilgrimage to Shakespeare’s birthplace. John Quincy Adams felt comfortable “mansplaining” Othello, King Lear, and Romeo and Juliet to Fanny Campbell, the leading Shakespeare actress of the age. Shakespeare’s histories and tragedies put leaders under extraordinary pressure—and then turn up that pressure even further, until those leaders fail. American presidents are, in many respects, ideal readers of Shakespeare; they understand what it means to lead under pressure, and then to discover that the political gifts that brought them into power often had little to do with maintaining it.

The book focuses on the way that Shakespeare has been employed to articulate division throughout American history. Does Shakespeare have the power to do the opposite? Can his work be used as a tool for empathy and healing?

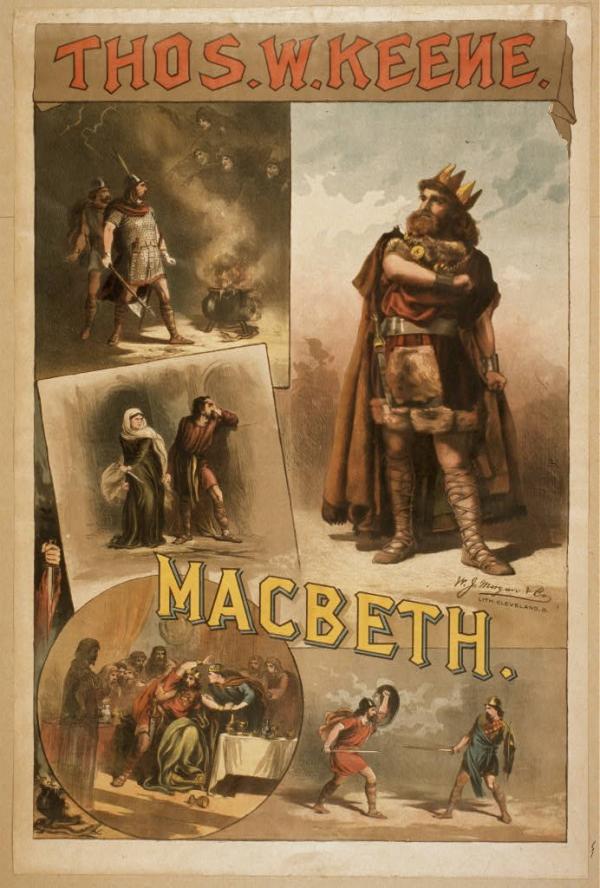

Absolutely. There isn’t much common ground in America today, and Shakespeare’s plays, still valued and admired by both the Left and the Right, offer one site where we can still meet and air our disparate views. It’s only through conversation, and through seeing the world through the eyes of others, that change occurs. I can’t think of any writer whose works better invite that sort of empathic response—whether it is allowing us to see the humanity of a Shylock or an Othello or experience the injustice Caliban feels. I might add that in the depths of the Civil War, having witnessed the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans in the war in the North and South, Abraham Lincoln—to my mind the most insightful reader of Shakespeare in our nation’s history—turned to Macbeth’s great soliloquy, the one that begins: “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow / Creeps in this petty pace from day to day.” “It comes to me,” Lincoln told a friend who heard him recite these words, “like a consolation.”

Do you think the performative nature of Shakespeare’s work makes it more conducive to expressing political difference than a text that cannot be performed?

Performance demands choices. Political differences are markedly different on the page and on the stage. Just consider the versions of Julius Caesar in recent years, in which the assassinated Caesar is seen as an Obama look-alike, and then, in a production a few years later, as a Trump look-alike. And it’s not just political difference. What does it mean when a woman is cast—as leading actors have been in recent years—as King Lear, Richard II, and Hamlet? Is Othello to be performed by a white or a black actor? What does it say about our country that an African American could not play Othello on Broadway until the 1940s? We respond viscerally to what we see onstage—especially to race and gender.

Shakespeare studies is a rich and varied field, and there seems to be a new interpretation or discourse surrounding the Bard every day. What do you see as the future of the field?

There are new interpretations of his works because our understanding of our world keeps changing, and scholarship races to keep up with those transformations. Take something as obvious today as climate change. Shakespeare’s works are rich in allusions to environmental disaster, but its only recently that scholars have turned their attention to these passages. Shakespeare keenly understood that the meanings of stories changed over time. That’s why he constantly took old plays like King Lear, Hamlet, and Henry V, the plots of which he did not invent, and reinterpreted them to speak more directly to his own cultural moment. As for the future of the field: there is no question that far more attention is going to be paid to race, especially in an American context.

What about the future of Shakespeare in the American classroom?

I hated Shakespeare when I studied his plays in high school and swore never to take a Shakespeare course in college (and never did). Happily, Shakespeare is no longer taught in the same rote way—at least I hope not. Thanks to wonderful institutions like the Folger Shakespeare Library, teachers now have access to innovative ways of introducing young people to his work, through performance, video, films, podcasts, and much else, all of which help remove the barriers that stand between us and these four-hundred-year-old plays. The last time anybody counted, roughly 90% of high schools in the U.S. still taught Shakespeare, and he is the only author that the Common Core recommends that all students study. So, I think that his future—at least in American classrooms--is pretty secure. But there is no substitute for seeing his plays onstage. One of the great gifts of the National Endowment of the Arts in recent decades has been “Shakespeare in American Communities,” succeeded of late by “Shakespeare for a New Generation,” exposing tens of thousands of Americans across the land to Shakespeare in performance.

What about this project surprised you? Did the finished product look how you expected it would from the outset?

I keep a book diary from the day I begin a project and am always surprised by how much a book changes over the course of researching and writing it. My book is framed by a controversial production of Julius Caesar staged in Central Park in the summer of 2017—which took place well after I contracted to write the book. My experience witnessing what took place in and around that production profoundly shaped my thinking about everything from the Astor Place Riots of 1849 to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865. Books are bumpy rides—and rarely turn out as first imagined. This one certainly didn’t. I never learned as much researching a book as I did with this one. Like many Americans, I know far too little about my nation’s past.

You’ve spent your career publishing widely on Shakespeare and Elizabethan England. What’s next for you?

That’s a tough question. I spent a quarter-century immersing myself in the day-to-day life of Shakespeare in the years 1599 and 1606, only to turn my back on England and confront something I knew all too little about: Shakespeare’s impact on America. I write my responses to these questions in the midst of terrible crises facing America: a frightening pandemic, massive unemployment, and a cultural movement that is forcing us all to confront unresolved issues of racism and injustice. These interconnected crises are hard to grapple with—which has sent me back to Shakespeare, who lived through and wrote about plague and social unrest. In addition to writing about Shakespeare, I also work with theater companies, advising productions and learning from the actors. I’ve spent the past few weeks advising a radio production of Richard II with an extraordinary group of actors, many of them African American, which has helped me understand the current moment—as well as what’s at stake in that history play—in ways I never grasped before. Perhaps I’ll have a chance to write about these experiences in my next book.

James Shapiro received an NEH Public Scholars award (FZ-255906-17) to support research for Shakespeare in a Divided America (Penguin Press, 2020).

The Public Scholars program supports well-researched books in the humanities written for the general public. For more information on the NEH Public Scholars program, or to apply, see the program’s resource page. Contact @email with questions.