Revolutionary Things: An Interview with NEH Fellow Ashli White

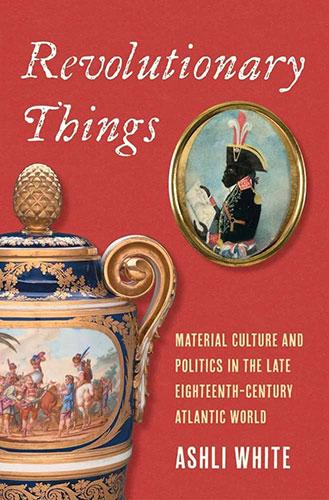

During the Age of Revolutions, ideas of equality and freedom, “occurred at the level of everyday life,” writes NEH Fellow Dr. Ashli White. In her recent publication, Revolutionary Things: Material Culture and Politics in the Late Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World (Yale University Press, 2023), White argues that objects contributed to the ideological changes in the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions. By centering her research on everyday objects, White includes perspectives from “enslaved and free, women and men, poor and elite.” Through her analysis of household objects, military clothing and accessories, and visual sources, White nimbly weaves together a transnational history that enriches our understanding of the Age of Revolutions. I recently spoke with White about her research, methodology, and the importance of material culture.

What are the origins of this project? What inspired your research?

In researching my first book about the impact of the Haitian Revolution on the early United States, I came across references to objects from that revolution in American cities. Some were brought by Saint-Dominguan exiles, but others—like a life-sized wax figure of Toussaint Louverture—were not. These transatlantic things did not fit into the narratives about the role of material culture in emerging national political cultures. And these objects did not inform sweeping narratives about the Age of Atlantic revolutions either. I was curious to see if these border-eliding objects might offer a fresh perspective on this era’s politics. Because I had attended the amazing graduate program in early American culture at Winterthur, I was fortunate to have some material culture methodology already in my toolkit.

Readers often learn about the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions through textual sources that privilege elite, white, and male authors. How does focusing on material culture broaden our contemporary view of the actors involved in these politically charged times?

People in the eighteenth-century lived in material worlds. Whether poor or elite, enslaved or free, female or male, they all had knowledge of and experience with things—a circumstance which is not the case with texts. To be sure, there were inequalities in individuals’ engagements with material culture: class, race, and gender hierarchies shaped people’s material worlds, and the legacies of this disparity persist in collections and archives today. Despite these real limitations, a material culture approach allows us to widen the range of political actors as well as the modes of political expression. In so doing, we reach a better understanding of what changed in this era, what did not, and why.

The book examines several material types of objects: ceramics, metalware, furniture, military clothing, cockades, maps, prints, and even wax figures. Why did you choose to focus on widely available objects rather than rare novelties?

For me, the more quotidian the object, the greater the possibility of accessing the broadest range of actors. This approach was crucial for ensuring that the Haitian Revolution was central to the narrative. In comparison to its U.S. and French counterparts, fewer things survive from the Haitian Revolution, and a significant proportion of what does endure was made by white actors outside of Haiti, with their own agendas. I address this dynamic in the book, but I also wanted to demonstrate, as much as I could, how Haitian revolutionaries turned to material culture to realize their goals of political transformation, and for that ambition, everyday things were essential.

Of these objects, which was the most compelling to research and why?

That’s a difficult question to answer because each genre of objects taught me something new and thought-provoking! In fact, working across genres was one of the most compelling experiences of this project. I was consistently impressed by the excellent and fascinating scholarship in each field. As the project developed, I found that my research into, for instance, military clothing would lead me to ask new questions about maps, or a miniature bone guillotine sparked fresh queries about prints. In other words, there was a good deal of cross-fertilization that I had not expected when I first began the project but was one of the biggest intellectual takeaways for me.

In framing the book, you emphasize the importance of an “Atlantic perspective”, rather than focusing on just the United States, France, or Haiti. How does a transnational framework reveal the complexities of objects in this era?

As several scholars have pointed out, many eighteenth-century things are Atlantic, or even global, products. Objects with a “French,” “North American,” or “British” provenance depended on Atlantic connections for their materials: mahogany, cotton, indigo, silk, bone, various metals. And makers relied on these same far-flung trade networks to sell their wares. Despite this well-documented phenomenon, there is a tendency to highlight national provenance when appraising the political significance of objects. By taking into consideration their Atlantic attributes in the political realm, things become much more dynamic, much more contentious, and in my view, much more interesting.

Many of the objects you discuss in the book do not seem overtly political. How do seemingly apolitical objects become politicized?

I argue that context matters when we think of the politicization of objects in the age of revolutions. By way of illustration, consider plunder. In all three revolutions actors seized vast quantities of items from their foes—everything from military stores and weapons to high-style furniture and porcelain (like the fantastic Sèvres vase on the book cover). While these goods were not decorated with political motifs, they became politicized because of who appropriated them and how. What’s more, these goods were often sold at auction to support revolutionary (and anti-revolutionary) campaigns. The terms of acquisition and sale informed the consumption of these objects, as diverse buyers snatched them up and put them to new political uses in their homes. By tracking the movement of plundered things at each of these points, we can see how they and, as you put it so aptly, other “seemingly apolitical objects” had political meaning in this period.

In the second section, “Political Appearances,” you argue that clothing and personal accessories could change meanings depending on the wearer. I found your analysis of the tricolor cockade particularly insightful. While this accessory is a popular symbol of French Revolutionary ideals, how was this stable interpretation actually challenged by different wearers?

Cockades were accessible to many people because the material most often used to make them—ribbon—was affordable. As a result, women, the enslaved, and white men of various means could appropriate, expand, and then act on the revolutionary ideals associated with cockades. These accessories became flashpoints of controversy that exposed divergent views on revolution. When Democratic Republicans in the United States embraced the tricolor cockade, they imbued it with values that differed significantly, and conflicted with, those of the Black men and women in Saint-Domingue who also wore the tricolor. In this way, cockades stand as an emblem of age of revolutions—not for their tidy encapsulation of principles and political groups, but for the ways cockades manifested the instability, ambiguity, and tension of Atlantic revolutions as they happened. Cockades show us how things afforded the unlettered, the subjugated, and the disenfranchised with ways to take revolutions into their own hands.

In the conclusion, you discuss the idea of “nationalist material culture” and consider how objects with “verified provenance to a revolutionary person, place, or episode” are collected while objects with ambiguous backgrounds are more often ignored. If you could curate a cabinet of forgotten revolutionary relics, what would you display and why?

What a fun question! For my cabinet I might take a cue from Fred Wilson’s landmark exhibition, “Mining the Museum” (1992), and experiment with juxtaposition by placing objects in unexpected contexts. I might include a Parisian military uniform with the Haitian Revolution, associate confiscated Louis XVI furniture with Britain and the United States, or connect a Wedgwood creamware platter to revolutionary France. The goal would be twofold: to recapture the dynamic movement of items across revolutionary spaces and to urge observers to reflect on how context shaped meaning.

What do you hope people take away from your book? How does it reorient our understanding of the Age of Revolutions?

I hope that this book encourages readers not to take things for granted—and I mean “things” literally. Things were (and still are) vital to human existence. But their significance goes beyond basic needs and functions to participate in making meaning. In short, objects are active: people affect things and things affect lives in fundamental and sometimes unforeseen ways. Once we recognize this essential condition, then it becomes clear that we cannot comprehend the achievements and limitations of the Age of Atlantic revolutions without taking the consequences of things seriously.

Was there anything that surprised you as you conducted your research for this project?

I was surprised by so many things in researching this book—references I tripped across, genres of objects that suddenly came into view, themes that emerged. To be honest, the surprises are the best part of the process, and they reflect the privilege of working in many wonderful institutions. I am very grateful to the archivists, librarians, curators, and scholars who facilitated all those revelations by their careful stewardship of collections and by sharing their time and expertise with me.

What’s next for you and your work?

My next project is in a very early stage, but I am interested in applying material culture methods to interpretations of the eighteenth-century environment. I am beginning by exploring how people’s experiences of revolutionary warfare and of reconstructing damaged built environments shaped their understandings of their world.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Ashli White received an NEH Fellowship (FA-57087-13) and an NEH Summer Stipend (FT-59783-12) to support her research for Revolutionary Things: Material Culture and Politics in the Late Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World (Yale University Press, 2023). White is a professor and the chair of the history department at the University of Miami.

The NEH Fellowships program awards grants to individual scholars for projects—such as monographs, peer-reviewed articles, and critical editions—at any stage of development. Projects funded by the Fellowships program embody exceptional research, rigorous analysis, and clear writing, and they are of interest to scholars, general readers, or both. For more information on the Fellowships program, or to apply, see the program’s resource page. Contact @email with questions.