The Representational Database: A Look at Black Newspapers and their Digitization History

Britney Henry is an PhD candidate in English and Museum Studies at the University of Delaware studying Black popular culture and Black material texts. As a summer 2024 intern with the Division of Preservation and Access, she contributed to search tools for Chronicling America and researched the evolution of application requirements for the National Digital Newspaper Program. For this blog post, we asked Ms. Henry to share her findings about the grant program’s history and its impact on the availability of digitized historic newspapers.

Chronicling America is a free newspaper database created in partnership between the National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH) and the Library of Congress (LOC) through the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP). As of August 2024, Chronicling America has more than 4 thousand titles, 3 million issues, and 22 million full text pages to search. And thanks to the efforts of the state partners, LOC, and NEH, it continues to grow, adding more content almost daily.

Because of its large size and vast coverage, it is easy to mistake the database as comprehensive rather than representational of newspapers across the United States. Chronicling America aims, as stated in the current guidelines, or Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO), “to create a national digital resource of historically significant newspapers” (1). Its scope has expanded since the program’s inception in 2005. For example, in 2016, NEH and LOC expanded the date range of NDNP to include newspapers in the public domain published up to 1963. Additionally, NDNP began in 2012 to allow selection of titles in a small number of Western European languages. By 2016, LOC expanded the language capabilities of Chronicling America to allow submissions in more than 500 languages. Currently, Chronicling America includes 22 languages other than English. By expanding the temporal and geographical reach of Chronicling America, the database can encompass a fuller range of subject matter of critical importance to U.S. history. Most recently, Chronicling America has prioritized digitizing newspapers that include “underrepresented perspectives and histories,” as the more recent NOFOs explain.

Chronicling America’s quest to represent all people of every state and jurisdiction continues. As the NEH Pathways Intern working on NDNP this summer, I have brought some of my own dissertation research to bear on questions of representation in Chronicling America. My scholarship is interested in Black popular culture, specifically within the Black press.

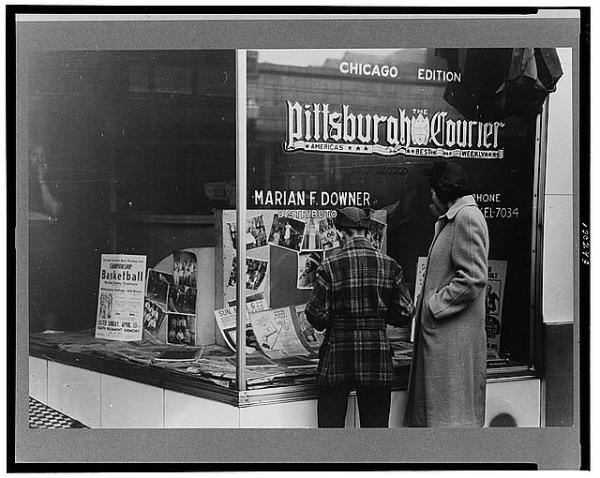

My dissertation research explores Jackie Ormes, a major figure in the cultural history of the Black press. Ormes is considered the first Black woman cartoonist, and her work appeared in the Pittsburgh Courier and the Chicago Defender. She published four comics: Torchy Brown in ‘Dixie to Harlem,’ Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger, Candy, and Torchy in Heartbeats. Searching through Chronicling America, I was surprised not to find any of Ormes’s work, whether it be comics or the articles she wrote for both newspapers. I knew that NDNP has made considerable efforts in recent years to include underrepresented histories, and yet neither the Pittsburgh Courier nor the Chicago Defender are there. If I filter the newspapers in Chronicling America to only African American newspapers, there are 317 titles, 52,041 issues, and 332,551 full-text pages. Additionally, I knew that a number of the contributing partners were deeply researching the Black press in their own states; see, for example, recent blog posts about such efforts from the South Carolina Library, the Tennessee Newspaper Digitization Project at the University of Tennessee – Knoxville, the Library of Virginia, and Arkansas State Archives. Moreover, LOC has made considerable efforts in the digitization of Black newspapers for Chronicling America, as it recently included a rather unique collection. In a recent blog post, LOC’s Nathan Yarasavage explains that “in 1947, the Library of Congress in cooperation with the American Council of Learned Societies microfilmed the original print pages of over 150 African American newspapers published in the U.S. throughout 19th and 20th centuries,” and that this microfilm has recently been digitized and added to Chronicling America. Fast forward to February 2022, “1,224 new pages from 103 African American newspaper titles through 28 states and the District of Columbia” were added.

And so, I was rather surprised then not to see two of the twentieth century’s most circulated and influential Black newspapers—the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier—in Chronicling America. These newspapers are key not only to understanding the Black press, but also Black history. Patrick Washburn describes the Defender’s editor, Robert Abbott, as “the Black press’s most influential publisher” (The African American Newspaper: Voice of Freedom). The Great Migration was Abbott’s campaign for Black southerners to migrate north for better opportunities, and he used the Defender to promote this cause. The Courier had its own successful campaign during World War II: the Double V Campaign, which fought for victory overseas as well as at home for Black people, as former NDNP speaker Matthew Delmont discusses in, Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad.

In my own work, these newspapers hold a hallowed space, for these papers were the first to have a Black woman cartoonist. Why then, I wanted to know, are these papers not in Chronicling America? Shouldn’t they have been some of the first Black newspapers included in the database, if not when Illinois and Pennsylvania joined the program, then surely in the more recent efforts to include newspapers from historically underrepresented communities in the database? The answer, I have come to think, has more to do with the history of newspaper digitization than the history of the newspapers, per se.

Turning to the funding guidelines, I read through the documents of years past as well as the current one to understand why these newspapers were not in Chronicling America. In the early days of Chronicling America, the guidelines clearly stated that “Previously digitized titles should not be candidates for inclusion” (NOFO 2007, 9). This meant that states could not propose to digitize content that a proprietary database already had digitized. With so much newspaper content not yet available, NDNP’s focus on that which had no digital access makes sense. Soon, however, that thinking seems to have shifted. In the 2009 NOFO, we begin to see a change in this policy: “While a previously digitized newspaper normally would not be a good candidate for inclusion, applicants may justify selecting such a paper in special circumstances” (5). The language in the 2025 NOFO relaxes this restriction even more, explaining that when selecting titles for digitization, states should consider “previously digitized newspapers” though they must still include a “strong justification for inclusion” (2). It remains true that some of the content behind paywalls cannot be included in Chronicling America because of contracts between holding libraries and subscription companies. And, of course, change is slow, and I suspect that the initial prohibition on paywalled content sent states looking for non-paywalled content, and they have not fully redirected their searches, despite the change in NDNP policies.

Currently the Defender and Courier can only be found fully digitized through Proquest’s Historical Newspapers (Black Newspapers) if you have institutional access. But I know now that Courier and the Defender, and numerous other important papers, are eligible to be included in Chronicling America, providing free access. Chronicling America is an incredible resource for those interested in historical newspapers and while it has come a long way in including newspapers from historically unrepresented groups, its work continues, and I look forward to seeing what significant titles are included as the database continues to grow.