Plymouth Colony and the Beginnings of Liberty in America: A Q&A with NEH Public Scholar John Turner

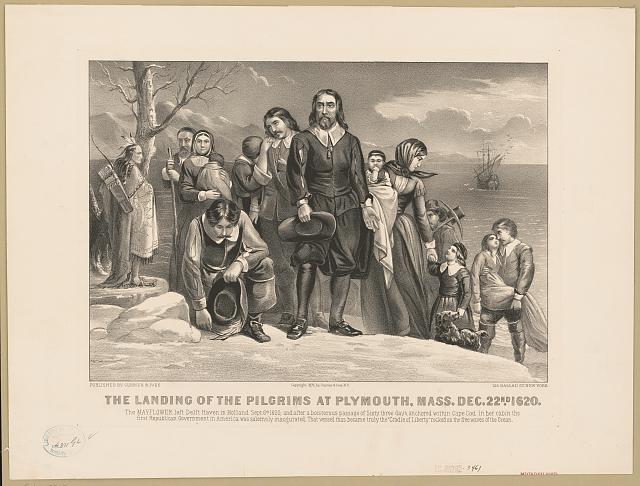

A romanticized representation of the Signing the Mayflower Compact, 1620. 1932 postcard after a painting by Jean L.G. Ferris

A romanticized representation of the Signing the Mayflower Compact, 1620. 1932 postcard after a painting by Jean L.G. Ferris

NEH Public Scholar John Turner wants to change what you were taught in elementary school about the Mayflower Compact being a precedent for democracy and how the Pilgrims brought religious freedom to the New World.

The Mayflower Compact, a short legal statement that provided a framework of government, was often touted by the nation’s early historians as one of the first steps in the evolution of self-government in the United States—a view that survived centuries. Meanwhile, the Pilgrims are seen as the importers of religious freedom to the United States and stalwarts of the idea that each person should be able to worship as they choose, a narrative that is repeated annually during Thanksgiving celebrations.

John Turner seeks to change these popular perceptions by showing that history is far more complicated. As he explains, after struggling to escape the Church of England, “The Pilgrims were determined to keep New Plymouth’s church and government in their own hands. They preserved their own liberty by denying it to others.” In his book, They Knew They Were Pilgrims: Plymouth Colony and the Contest for American Liberty, Turner sets out to reevaluate the history of the Plymouth Colony just in time for the 400th Anniversary of the Pilgrims' landing on Cape Cod.

It was a pleasure to discuss the book with him.

As a historian of Religion in the United States, what brought you to this particular topic?

I enjoy focusing new lenses on well-worn subjects, and the Mayflower crossing remains among the most iconic episodes within American collective memory. All Americans learn something about the Pilgrims and the Wampanoags in elementary school, and the so-called First Thanksgiving briefly intrudes onto our consciousness every November. Especially in light of the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower, it seemed an especially appropriate time for a reexamination.

I also found myself fascinated by what happened in Plymouth Colony after its first decade. In most tellings of colonial American history, the scene shifts to Boston after John Winthrop and his Puritan flotilla reach Massachusetts Bay in 1630. Plymouth Colony existed for another sixty years, and those years are filled with their own dramas: steadily worsening relations between English settlers and Wampanoag leaders; fierce and never settled debates over religious liberty prompted by the arrival of Quaker missionaries; and political revolts against both crown-appointed governors and elected colonial magistrates.

Why do you think so few people know about the first part of the Pilgrims’ journey through the Netherlands? It seems an important part of the story that isn’t often told.

Yes, the Pilgrims were exiles from England, but by way of the Dutch Republic. The majority of Mayflower passengers were separatists, men and women who had entirely rejected the Church of England and had formed their own churches. That was illegal according to English law, and in 1607-1608, there was a new wave of persecution against separatists. Therefore, many of them fled to the Dutch Republic, long a refuge for English religious dissidents. From Amsterdam, many followed separatist pastor John Robinson to the city of Leiden. In Leiden, the English separatists had a large measure of religious liberty. As long as they kept their heads somewhat down, they could worship as they saw fit. But that liberty was fragile, and as far as many of the future colonists were concerned, there was rather too much religious toleration in the Dutch Republic. They preferred to establish their own godly society on the other side of the Atlantic and hoped that their success would attract more English Puritans to embrace separatism.

Your description of the voyage across the Atlantic suggests that there was quite a cast of characters on board the Mayflower. Was there any one individual who captured your attention? Or perhaps your admiration?

Do I have to pick one? There are so many: Bastard children; a man (Stephen Hopkins) who had already crossed the Atlantic once and had barely escaped execution on Bermuda; and servants like John Howland, who survived falling into the sea during the crossing. The initial Jamestown venture included no women, but there were families on the Mayflower, including three pregnant wives. Stephen Hopkins’s wife, Elizabeth, gave birth to a son named Oceanus.

Your project, being published in the 400th anniversary year of the Mayflower landing, seeks to frame the journey of the Puritans of Plymouth Colony as pilgrims in more or different ways than previously explored. What made you think that there needed to be a change in the way that the story of the Pilgrims is retold?

There are several myths that need to be set aside or at least reexamined. Among them: That the Pilgrims favored religious toleration; that the Wampanoags welcomed the Pilgrims; and that the Pilgrims played a significant role in the broader trajectory of American political history. There are others as well, such as those surrounding Plymouth Rock and Thanksgiving. Take even the name “Pilgrims.” My book’s title comes from William Bradford’s history, in which he explained that he and his fellow colonists-to-be took comfort in the fact that they “knew they were pilgrims.” The reference was to the Epistle to the Hebrew from the New Testament, which teaches that all Christians are “strangers and pilgrims on the earth.” The Mayflower passengers and other early Plymouth colonies became known as the Pilgrims only around the turn of the nineteenth century

Because it is such an interesting distinction, will you describe the ways you contrast ideas on the “Christian Liberty” of New Plymouth and the later “Soul Liberty” of Rhode Island?

Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island, spent time in both Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth before being banished by the Bay Colony magistrates. After his banishment, Plymouth also wouldn’t let him settle on land it considered within its jurisdiction. Williams believed in a strict separation between church and civil government. No church taxes, no prohibited beliefs or practices. Other Protestants, Williams pointed out, wanted “their own souls only to be free.” And that was true in Plymouth Colony, which like the Bay Colony established a single religious option in each town. Plymouth’s leaders did permit a significant measure of “liberty of conscience.” No one had to join the established church or have their children baptized by its ministers. At first, there weren’t any church taxes, and, much of the time, attempts to enforce attendance at worship didn’t amount to much. But for the duration of the colony’s history, Plymouth’s magistrates never embraced “soul liberty.”

In the latter half of the book, you make out “freedom” as being very circumstantial, would you say that servitude, of one form or another, was more common in New England than many would believe?

Many men and women came to the colony as indentured servants. Some of those servants went on to receive political privileges and land, while others remained very much on the margins of communities. But the subject of servitude is a much bigger and more complex topic. In the wake of the 1675-1677 war (most commonly known as King Philip’s War), thousands of Wampanoags were taken captive. Some were exported as slaves. Others remained as slaves and servants within the colony. A few scholars, including Margaret Newell, have written important accounts of Native slavery in colonial New England. Still, I was surprised to learn just how ubiquitous Native servants and slaves were during the final decades of the seventeenth century. There were also African slaves in Plymouth Colony, especially in the western townships across from Rhode Island.

How would you like the public to react to this book?

By purchasing and praising it. More seriously, I learned a great deal about a range of peoples (Wampanoags, Quakers, Dutch Remonstrants) while writing this book, and I’m confident readers will find many things in They Knew They Were Pilgrims that will startle and surprise them. It’s important, for instance, to learn about the dispossession of Native peoples. Epidemics and wars were important, but so too were the many smaller acts that coerced Native leaders to sell land. Likewise, Americans who admire the Pilgrims for their faith might also examine the 17th-century Wampanoags who embraced Christianity.

In other contexts, you have addressed the challenges that many religious scholars seem to face when their scholarship and personal beliefs pull in different directions. Did that tension between your own views and your scholarship shape this particular project at all?

For many scholars of religion, this is a fraught matter, whether or not they admit to it. It’s easy to claim to be objective and above the fray, but that isn’t always possible. For instance, my own spiritual journey has been deeply shaped by the evangelical wing of American Protestantism. I continue to straddle the worlds of evangelical and mainline Protestantism (Presbyterianism). When other scholars treat evangelicals as caricatures or only as political pawns, it gets my hackles up a bit. I wrote my first book about a major evangelical movement. I hope I was fair to its members but not indulgent of them. At the very least, it was relatively easy for me to understand them, because I spoke their religious language.

But in terms of my research about Plymouth Colony, I really didn’t feel any of this sort of tension. Many American evangelicals have a warm appreciation for the Pilgrims and see them as kindred spirits. I think this is because they don’t know that much about them. The views of the Pilgrims are very foreign to nearly all streams of American religious and political thought today. As a historian who had written about 19th- and 20th-century subjects previously, the first thing I had to do was to orient myself in what is really a very different religious and political world.

What’s next for you?

I’m writing a biography of the prophet Joseph Smith.

John G. Turner received an NEH Public Scholars award (FZ-261386-18) to support research for They Knew They Were Pilgrims: Plymouth Colony and the Contest for American Liberty (Yale University Press, 2020).

The Public Scholars program supports well-researched books in the humanities written for the general public. For more information on the NEH Public Scholars program, or to apply, see the program’s resource page. Contact @email with questions.