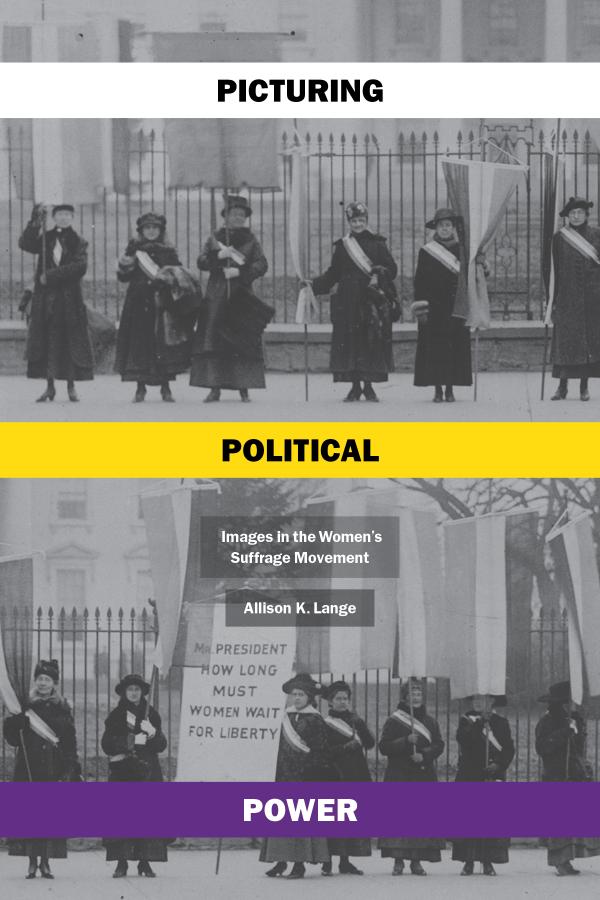

Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Q&A with NEH Summer Stipend Recipient Allison Lange

How have women cultivated their own political careers using visual media? How did sexism infiltrate popular culture through photographs and political cartoons? And how did women maintain agency and power during their fight to secure the vote? NEH Summer Stipend recipient Allison Lange explores these questions in Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement. From America’s founding to the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, Lange “tracks the way that women gradually transformed public images of gender and political power.” From Phillis Wheatley to Susan B. Anthony, Lange decodes the unique visual language women used to gain their political power. Lange’s research is historical, but it also relevant to the modern day: “A familiar vision of political womanhood remains powerful because criticism of women as political leaders has changed little,” Lange writes. I spoke with Lange about the historical barriers to political power and women’s strategic use of visual media to influence their political careers.

Throughout U.S. history, how did suffragists and feminist activists use visual rhetoric to their advantage?

During the late nineteenth century, women’s rights activists launched a visual campaign to convince the public that women could be powerful political leaders. Most popular periodicals and prints featured cartoons that mocked women interested in politics. Images depicted them as masculine monsters who wanted to take over men’s roles and abandon their homes and children. By the 1910s, women’s voting rights activists created a national campaign to emphasize that voting women would be better mothers and citizens.

Why are these women’s stories still important to study today?

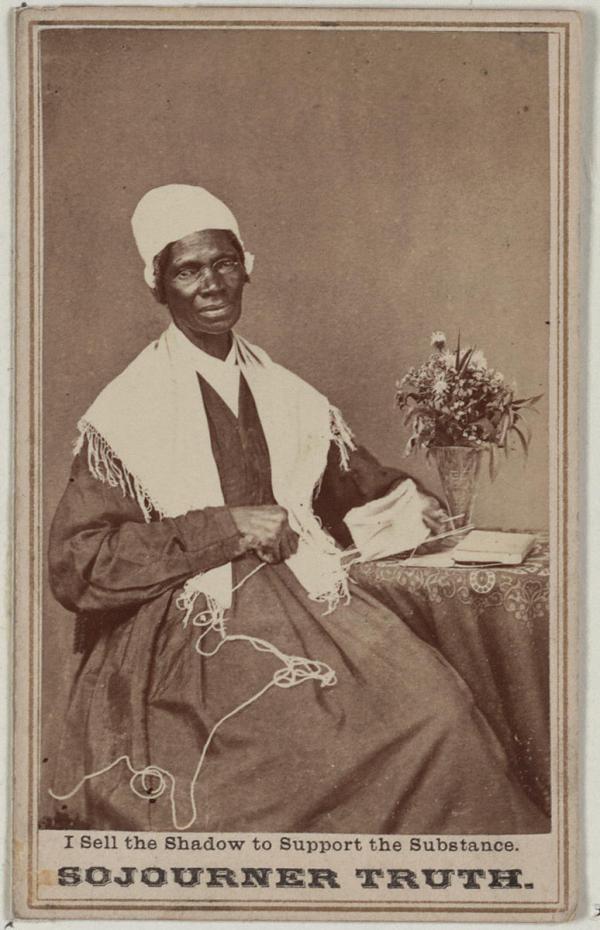

Women’s voting rights activists designed one of the first national visual campaigns in U.S. history. They developed innovative strategies based on new image technologies over the course of several decades to reach a wide audience. Portraits of leaders like Sojourner Truth and Susan B. Anthony are well-known today because of their work to create a visual campaign over a century ago.

Which image from your book would you consider the most important to America today?

A portrait of Sojourner Truth, a formerly enslaved person who became a famous advocate of women’s and civil rights, helped spark the visual campaign for women’s voting rights. She wanted her portrait to challenge racist and sexist stereotypes and secure support for her causes. Truth copyrighted her portraits herself—which was very unusual at the time—and strategically chose how she wanted to appear in her photographs.

What strategies did you use while digging through archives to find the images featured throughout your book?

I wanted to understand what kinds of images Americans in the past regularly encountered in their daily lives. So, I examined popular illustrated publications like Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper as well as prints by famous companies like Currier and Ives. The papers of suffrage organizations and artists also featured fascinating pictures. Most importantly, expert archivists and fellow scholars gave me incredible suggestions.

Your book includes dozens of images, spanning from portraits of Martha Washington to photographs of suffragettes in the 1910s. How did you go about choosing which images to include (or exclude)?

Selecting the images for the book was tough! I chose pictures that many Americans saw to demonstrate how common these ideas about gender and politics were. The Library of Congress is an incredible resource because many of their images are digitized and freely available for scholarly publications.

What was the most surprising thing you found during your research?

I am still surprised by how little modern images of men and women in politics have changed over time. On social media and news sites, we are still most likely to encounter pictures of older white men in powerful positions. And, just like so many of the nineteenth-century cartoons that I found, memes continue to mock women in politics as too masculine or—on the other hand—too interested in frivolous, feminine fashions. Similar to the suffragists, many continue to challenge dominant images of political power.

Throughout the book, you discuss how Americans used an ever-evolving visual language in their political cartoons, portraits, and other visual media. What was the most challenging aspect of analyzing and “de-coding” these images? How did you overcome this challenge?

The most difficult part of interpreting historical images is understanding their original context. I regularly tell my students to put their nineteenth-century glasses on! Often, when I show my students a cartoon that mocked suffragists by portraying them as political leaders, they think they are looking at a feminist image. However, once they learn more about the past, they recognize the clues that tell us that the artist wanted their original audience to laugh at these women.

What similarities and differences do you see between the feminist visual rhetoric of nineteenth- and twentieth-century America and present-day America?

By the end of the suffrage movement, activists had a national visual campaign designed by professionals and carried out by their organizations. Today we tend to value more personal representations of feminist ideas. For example, posters from the recent Women’s Marches illustrated a range of images, issues, and witty slogans. Despite these differences, today’s feminists remain focused on issues like equal pay and access to the vote, just like activists did over a century ago.

Now that Picturing Political Power is finished, what’s next for you?

I learned from my first book just how much historical images laid the foundations for the modern ones that we constantly encounter on social media, news sites, and numerous other platforms. My next book reveals how historical pictures shaped recent viral images that reinforce (and challenge) our current ideas about gender and politics.

Allison Lange received an NEH Summer Stipend Award (FT-254705-17) to support research for Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement (University of Chicago Press, 2020). Lange is a professor of history at Wentworth Institute of Technology in Boston, Massachusetts.

The Summer Stipends program supports continuous full-time work on a humanities project for a period of two consecutive months, stimulating new research in the humanities and its publication. For more information on the NEH Summer Stipends program, or to apply, see the program’s resource page. Contact stipends@neh.gov with questions.