Phantom Records: A Two-Part Series on Searchability and Records in Chronicling America, Part 1

The National Digital Newspaper Program’s (NDNP) website, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers boasts over 18 million pages of America’s newspapers published between 1777 and 1963. Such a wealth of information begs to be explored for various projects, such as conducting genealogical research, diving into the history of the neighborhood one calls home, exploring images from newspapers past, and of course, performing educational and academic research. But how does one search through this number of pages to pinpoint specific information of use to one project? My interest in Chronicling America began during my dissertation research, and I have had the opportunity to explore Chronicling America in depth as part of my work as a summer intern for the NEH’s Division of Preservation and Access. In two blog posts, I will explore some of the questions of searchability that inform my day-to-day work for the internship.

My work this summer on Chronicling America is, at its core, about enhancing the records for editors mentioned in title essays published on the site, specifically for titles in the ethnic press. Before we dive into how the Chronicling America editorial records are enhanced (the subject of the second installment in this series), let’s first consider: how can we use Chronicling America to learn more about a person’s role in history. To explore this question, we’ll use the case study of Madame Restell. Restell, a figure from the nineteenth century, ran what we would call today an abortion clinic in New York City. She was nicknamed the “wickedest woman in New York” by the press and referred to pejoratively as an “abortionist” for her complicated role connecting patients with abortions at a time when abortion was newly criminalized.

Searching a database with more than 18 million pages may seem like quite the task at the outset. Chronicling America features two search functions, a basic search and an advanced search. The basic search runs the search terms through the texts of newspaper pages, which software derives from the scanned images, and that are identified within a geographic or temporal range. Under advanced search, users run their search terms and phrases through not just the state and date range, but they can limit their search to the pages of a particular newspaper title. In advanced search, users also have the option to search by one of the 19 languages in Chronicling America.

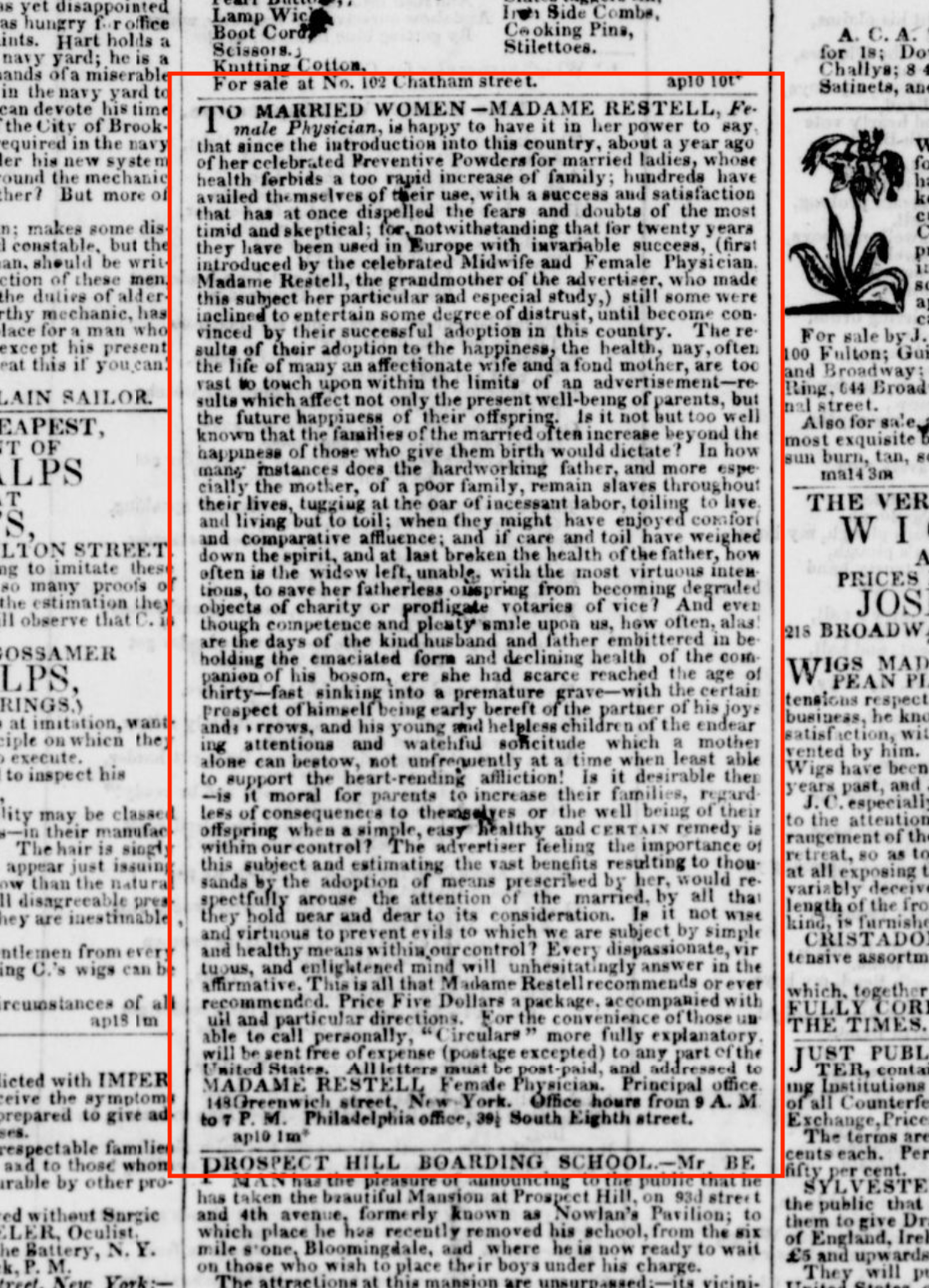

Like most text derived from scanned images, Chronicling America uses optical character recognition (OCR) software to create searchable data. When a search term is entered, Chronicling America checks the term against the OCR text of each page’s image. OCR is not fully reliable – the phenomenon of “dirty OCR” or the computer transforming the text on a digital image into unrecognizable words results in some less than accurate search results. Using the case study of Madame Restell, we can explore what happens when we use variable search terms and when the material being searched might not fully reveal all instances of the search term in the material.

Say we wanted to learn more about the context in which Madame Restell’s name appears in print during her lifetime. Before we run a search term through Chronicling America, we would first need to ask ourselves, How would the press have referred to this woman? Is “Madame Restell” the most recognized name to use as a search term? To see what other name variants might have existed, we check the Library of Congress’s Name Authority Files (LCNAF). Name Authority Files are part of a controlled vocabulary that offers users an authoritative name by which to refer to people, places, organizations, etc. When we search the LCNAF record, we see “Madame Restell,” an alias, is indeed the authoritative name recorded in the LCNAF record. The LCNAF also records her variant names, the other names by which she was referenced, including her birth name Ann Trow, her married name Ann Lohman, as well as her daughter’s name, Caroline, which she was mistakenly called by the press. Due to the nature of Madame Restell’s work, she relied heavily on her alias to avoid prosecution, and this reliance on an alias makes her personal life more of a mystery. If we want to gain insights into Restell's work and Lohman's life, we need to search with all of these variations of her name.

Having taken note of the name by which Madame Restell is listed in the LCNAF, as well as the variants of her name, we can return to our search in Chronicling America. If we run an advanced search for “Madame Restell” in New York newspapers from the year Restell posted her first business advertisement (1839) to two years after her death (1880) what might we find?

The answer is quite a lot:

The search using “Madame Restell” returned 853 results, mostly from sensational penny press newspapers such as the New York Sun, Herald, and Tribune, all of which featured Restell’s advertisements as well as coverage of her court battles and death. These search results include any mention of Restell’s name in newspaper pages as recognized by OCR.

What happens, though, when we use the same search parameters but switch out her alias name to one of her variant names, her married name Ann Lohman?

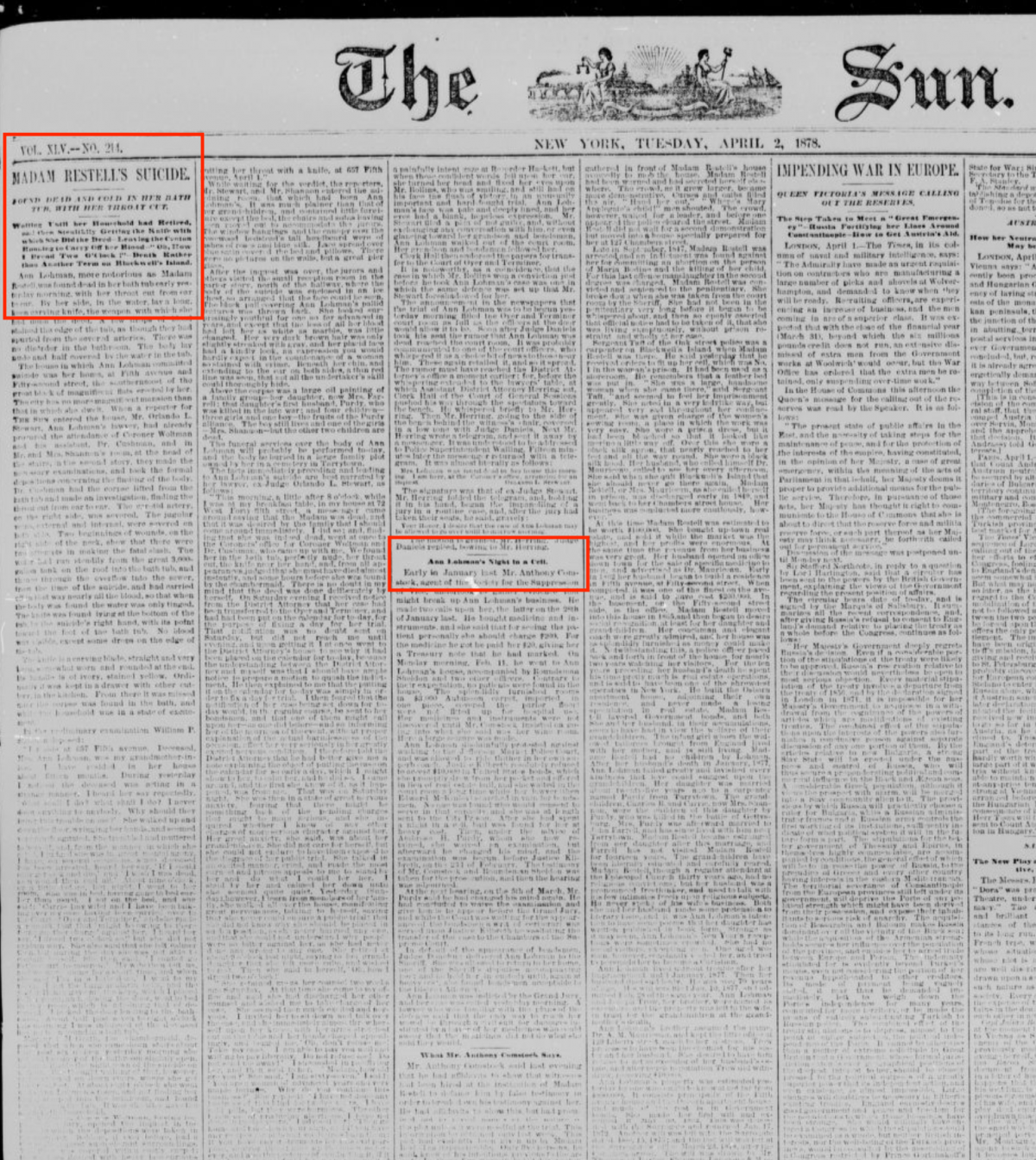

Perhaps as expected, the OCR search with the variant “Ann Lohman” yields just seven results, much fewer than the 853 for “Madame Restell.” However, while the search with “Ann Lohman” does not yield as many results, the first item in the list takes us to coverage of Restell’s death – a sensationalized obituary, to be sure, but one that covers four columns in the paper and is essential to exploring how Restell/Lohman was understood in the nineteenth century. The search with a variant, Restell’s married name, targets the results and excludes Restell’s published advertisements and other sensational coverage. The different search terms focus on different aspects of life for Restell/Lohman and offer a more complete picture of her role in history almost two centuries ago. The LCNAF record represents a controlled vocabulary, and through its inclusion of alternatives to her “authorized” name, it provides the key for unlocking the historical record about a woman who spent much of her life evading authorities. In other words, we can use the LCNAF record to discover the nonauthorized versions of Restell's name as well. We are then, in effect, using the official record to read against that very record, to uncover the names obscured in history.

Jeannette Schollaert is a summer intern in the NEH Division of Preservation and Access and a PhD student in the English Department at the University of Maryland, College Park where she is completing a dissertation entitled, “Censors and Shouts: Technologies of Abortion in American Fiction.”