Lincoln: Shakespeare’s Greatest Character

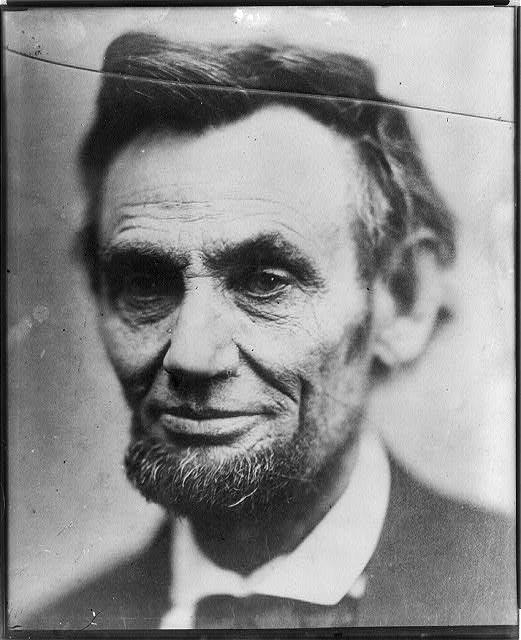

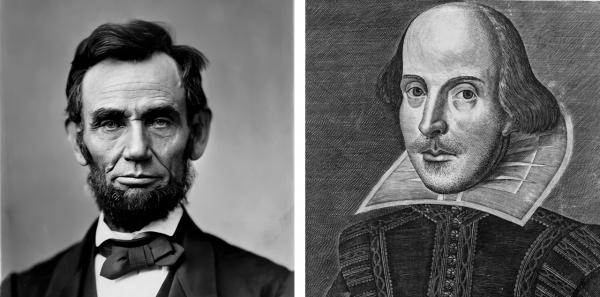

Head-and-Shoulders Portrait of Abraham Lincoln. Thought to be among the last photos of him alive. February 5th, 1865. Photographed by Alexander Gardner.

Portrait of William Shakespeare. Probably painted around 1610 by John Taylor. Oil on canvas. Located in the National Portrait Gallery.

Lincoln photo: Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Shakespeare photo: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Head-and-Shoulders Portrait of Abraham Lincoln. Thought to be among the last photos of him alive. February 5th, 1865. Photographed by Alexander Gardner.

Portrait of William Shakespeare. Probably painted around 1610 by John Taylor. Oil on canvas. Located in the National Portrait Gallery.

Lincoln photo: Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Shakespeare photo: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

By Ethan Anderson, University of Missouri

Division of Research intern, summer/fall 2020

Abraham Lincoln, 16th President of the United States, sat across the table from Union Officer Le Grand B. Cannon in Fort Monroe, Virginia, in May of 1862. They were the only two around, the senior officers having left for their field assignments, not due to return until later in the day. A book of Shakespeare’s work—which Lincoln had borrowed from a general at the Fort —lay open on the table between them. Cannon had been hard at work, but Lincoln, incapable of action until his absent officers returned, had spent the preceding hours at an empty desk, his nose buried in the small volume of the Bard’s plays. This was not out of character for Lincoln; he had an intense love of Shakespeare and filled many of the elusive free moments he had as Commander-in-Chief with those famous verses. So great was this love that those who knew him well (and even those who didn’t) had grown accustomed to the melancholy, contemplative president breaking into long Shakespearean recitations anytime he got the chance. It was with this intent that Lincoln had approached Cannon on that day in May, offering the officer a break from work in exchange for an audience. Cannon, of course, accepted the invitation.

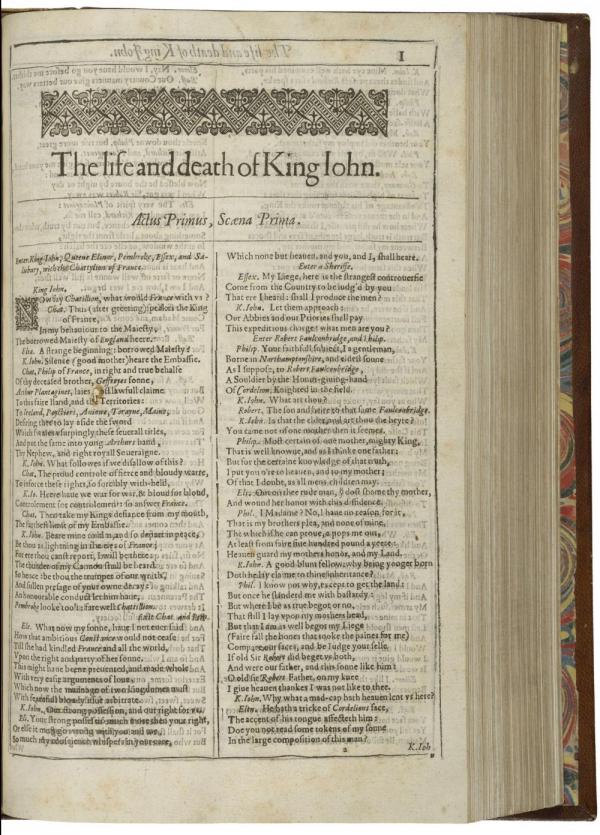

Cannon recalled Lincoln reciting from a number of the tragedies, saying that he “was surprised to find how well [Lincoln] rendered it all.” But the president seemed particularly taken with the lesser-known Life and Death of King John on that spring morn. It was a relevant choice. The play, written by Shakespeare in the mid-1590s, recounts the disastrous end of King John’s reign. Thematically, it reckons with the question of authority, asking if its legal precedent or military might that makes a ruler legitimate. Beyond this philosophical dilemma, the play presents a harrowing picture of powerful individuals in extreme crisis and details a king’s fall from grace as his kingdom crumbles around him into revolt and violence. No doubt this resonated with Lincoln in 1862. The bloody Civil War raged on, and Union victory was nowhere in sight. Throughout the nation, Lincoln was widely considered an incapable president, and even his supporters decried him as nothing more than a well-meaning fool. All of this combined must have made him feel like a character in King John, which late Shakespearean scholar David Bevington describes as “a study of impasse, of tortured political dilemmas to where there can be no clear answer.” Could anything apply to Lincoln’s position more perfectly?

But beyond its insight into the struggles of a leader under immense pressure, Lincoln seems to have gotten something far more personal from this play as well. In the late winter of 1862, just three months before his visit to Fort Monroe, Lincoln’s son William had passed away. One of the characters in the play — Lady Constance — who also loses a child in tragic circumstances, laments her feelings in a heart-wrenching soliloquy. It was this passage that Lincoln read aloud to Officer Cannon: “Grief fills the room up of my absent child,/Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me” (3.4.1479-1480). Cannon tells us that Lincoln stopped reading after this and asked him, “Did you ever have a dream of a lost friend and feel that you were having a sweet communion with that friend, and yet a consciousness that it was not a reality?” Cannon responded that he had indeed had such an experience. Lincoln simply said, “That is the way I dream of my lost boy Willie.” Then he began to sob.

The story of Honest Abe growing up in a tiny, rural cabin and climbing his way to the highest office in the land is perhaps the most potent and widely known self-creation myth in the American cultural ethos. Well documented alongside his domestic circumstances is Lincoln’s hunger for knowledge and his autodidactic genius. One of the greatest speech writers in American history taught himself to read and write without ever going to school for more than a year. Evidence suggests that Shakespeare was present in Lincoln’s quest for self-knowledge from the beginning. Growing up on the sparsely populated frontier, Lincoln’s cultural access was about as large as comprehensive as his educational one; he probably didn’t attend a theater until well into his adulthood, and the books available to him during childhood were limited. Most rural households at this time only possessed a Bible and a volume or two of classic English literature. However, it is likely that Lincoln’s mother or stepmother owned a copy of William Scott’s Lessons in Elocution, a rather popular educational textbook in the early 19th century which utilized (among other literature) Shakespearean verse and soliloquies to help teach effective speaking, reading, and writing. This likely formed the core of Lincoln’s introduction to Shakespeare during childhood and could well have been his primary source of educational instruction for much of his adolescence. If this is true, it suggests that Lincoln’s verbal and academic development was in many ways ushered in through Shakespeare’s words.

Regardless of how he first came to Shakespeare, the playwright’s words reappear throughout Lincoln’s life. In 1836, he was finally admitted to the Illinois Bar, giving him the resources to purchase his own Shakespeare anthology at some point in the years following. It seems he used this copy regularly, as stories abound of the tall, lanky lawyer traveling the court circuit with a book of Shakespeare in his satchel, reading it when he was able.

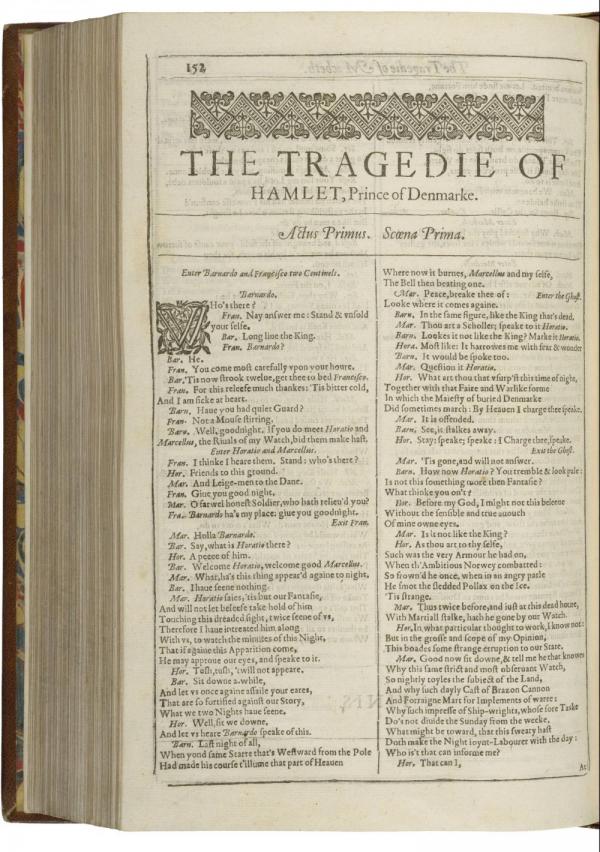

But it’s when Lincoln finally gets into the White House that we see his engagement with Shakespeare soar to new emotional heights. In his last two years as president, he had a small amount of free time from his duties, and went to the theater quite often, finally getting to see the plays he so dearly loved acted on stage. As a result, he started a brief correspondence with one of the leading actors of the day, James Hackett. Writing to him on August 17th, 1863, Lincoln says, “Unlike you gentlemen of the profession [professional actors], I think the soliloquy in Hamlet commencing ‘O, my offense is rank’ surpasses that commencing ‘To be or not to be.’” The soliloquy he refers to comes in Act 3, Scene 3 of Hamlet, when King Claudius admits to the audience that he did indeed kill Hamlet’s father. It reads:

O, my offence is rank, it smells to heaven; [...]

Though inclination be as sharp as will;

My stronger guilt defeats my strong intent;

[...]What if this cursed hand

Were thicker than itself with brother's blood,

Is there not rain enough in the sweet heavens

To wash it white as snow? [...] (3.3.2318-2328)

One wonders why Lincoln loved this soliloquy more than its famous “To be or not to be” counterpart. The latter is a widely quotable meditation on the most essential questions of existence, depositing that a human’s greatest choice in life is to continue living or otherwise end the life they are given. Its implications touch on many aspects of existing alongside trauma, and could well have been useful — comforting, even — to Lincoln as he struggled deeply with personal and national tragedy. Comparatively, King Claudius’s “O, my offense is rank” speech — the speech Lincoln preferred — is hyper-focused on the question of guilt and fratricide. But Lincoln never killed his brother, or anyone else for that matter. Why did such a murderous meditation strike him so deeply?

It could be that Lincoln was reading Shakespeare in those executive years with a monopolizing eye toward how they spoke to his own experience as president, using the plays, in part, to give voice to the natural guilt he felt as leader of the bloodiest war effort the nation had ever endured. A somber remark Lincoln made to a Congressmen during a particularly horrible period of the war provides a potential corroboration: “Doesn’t it seem strange to you that I should be here? Doesn’t it strike you as queer that I, who couldn’t cut the head off of a chicken, and who was sick at the sight of blood, should be cast into the middle of a great war, with blood flowing all about me?” Though Lincoln never felt any regret for pursuing the war, it would be hard to imagine that the weight of the bloodshed didn’t affect him in some way. No matter how righteous and necessary the cause, any empathetic human who leads other humans through a war would certainly, like King Claudius, feel the weight of their “brother’s blood” — and Lincoln was nothing if not deeply empathetic.

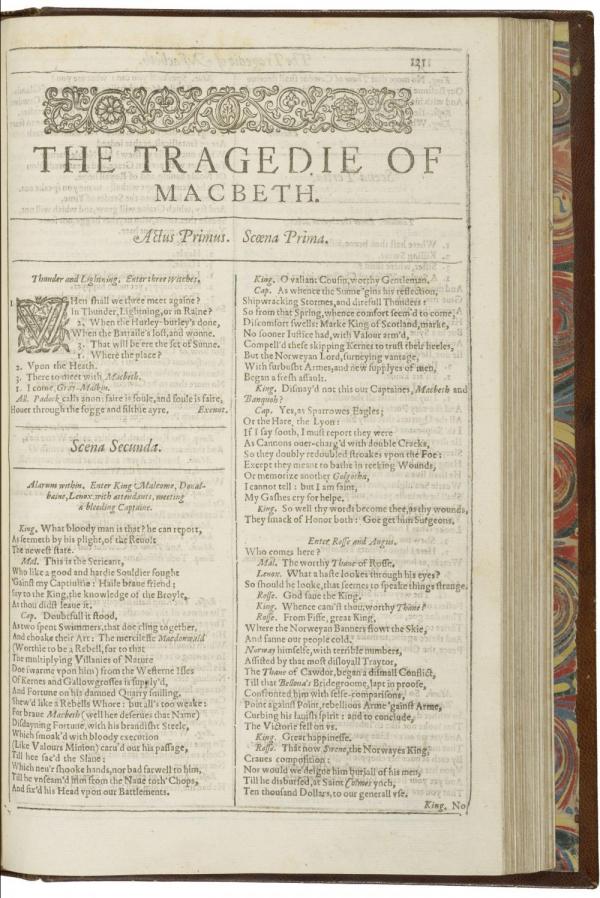

But of all the Shakespeare plays he read in office, Lincoln loved Macbeth the most, writing, “I think nothing equals Macbeth. It is wonderful.” Senate Secretary John Weiss Forney provides us with valuable insight into what Lincoln got from the ominously named “Scottish Play.” One evening, Forney discovered Lincoln sitting alone, his face “ghastly pale, the dark rings were round his caverned eyes, his hair was brushed back from his temples [...]” A book was open on the President’s lap. True to character, he asked Forney if he might recite a passage from Macbeth that he said “comes to me tonight like a consolation.” He commenced reciting the title character’s most famous soliloquy:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing. (5.5.2376-2385)

Shakespeare’s language here is incredible. It is spoken after Macbeth has achieved absolute control of the Scottish crown. However, through the power he has accomplished nothing, and the very kingdom he sought to control has turned against him. Vicious enemies are closing in on the castle, soon to enter the throne room and kill him. More than the looming physical threat however, it is the immense sorrow and desperation of powerlessness that Macbeth here laments. Even after achieving supreme power in a political sense, he realizes he cannot change the course of destiny.

But Lincoln wasn’t a tyrant. While Macbeth suffered beneath the weight of crushing guilt and excesses, Lincoln bore no such sins. Instead, he got something far more abstract from Macbeth’s famous soliloquy. Throughout his life, Lincoln was deeply attracted to the idea of unchanging destiny, and used this ‘predestination’ mindset to help him survive even the most traumatic of events. In many ways, he saw his presidential legacy not as the result of well-ordered strategy and political planning, but as the sheer result of some higher order of which he was merely an often unwitting tool. “I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me,” he said in an 1864 letter. There was no modesty in this; he meant every word, and it’s not hard to understand why. Here was a man who, upon entering the presidency in 1860, had held no higher a political office than one term in the House of Representatives, and who only a few years earlier had failed to be elected senator of Illinois. And when he finally did get elected as president, half the nation seceded. As if leading the nation through a great civil war wasn’t enough, he lost children and loved ones at the same time, and the country he was devoted to thought extremely poorly of him. It is Macbeth’s sense of hopelessness against the power of destiny that made Lincoln feel a connection to the speech. He was deeply comforted by Shakespeare’s supreme intuition into the feeling of almost existential powerlessness that often plagues people in positions of incredible responsibility. No matter how brilliantly successful Lincoln’s presidency would prove to be in retrospect, while living, he probably often felt like “an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

As we unfortunately know, the final act of Lincoln’s story was no less Shakespearean than the preceding ones. He was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth on April 15, 1865, in a balcony of Ford’s Theatre, less than two months into his second term. After shooting Lincoln in the head, Booth screamed to the crowd, “sic semper tyrannis” (“such is with tyrants”), words attributed to Brutus after assassinating Julius Caesar, which Shakespeare’s play of the same name masterfully depicts, a play Booth had acted in frequently. Tales even suggest that in the week preceding the assassination, Lincoln had disturbing dreams of visiting his own funeral. As a result of this nightmare, the story goes, a sense of dread seemed to overtake his final days. When he shared this with a trusted friend, he alluded to Macbeth, saying the feeling of doom “has got possession of me, and, like Banquo’s ghost, it will not down.”

Did Lincoln really have some dream-like intuition of his forthcoming death? Perhaps, but perhaps not. What’s more significant is that this myth, framed as it is in Shakespearean allusions, still persists in our cultural memory of Lincoln. In fact, the seemingly organic interconnection between Shakespeare and Lincoln is one that has been noted time and again by scholars and writers alike. Numerous articles, podcasts, and scholarly lectures document Lincoln’s rich engagement with the Bard. There’s even a book-length treatment the subject. Even when a scholar seeks to talk about Lincoln alone, Shakespeare still seems to make his way in. On only the third page of two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David Herbert Donald’s NEH-funded Lincoln biography, a reference to a Hamlet quote that Honest Abe’ loved appears: “There’s a divinity that shapes our ends, / Rough-hew them how we will.” Perhaps it is logical that Shakespeare might come up in such a comprehensive study of Lincoln, given his intense love the author’s work. However, even when literary critics simply discuss Shakespeare’s influence in America, Lincoln almost always appears there too. When the Library of America published an anthology of writing about Shakespeare throughout US history entitled Shakespeare in America, a letter that Lincoln wrote to a famous Shakespearean actor appears. When NEH Public Scholar James Shapiro wrote Shakespeare in a Divided America about Shakespeare’s role in American history, he devoted an entire chapter to President Lincoln and the Shakespearean connections surrounding his assassination.

Why do we care so much about Lincoln’s love of Shakespeare? Shakespeare’s work depicts, on almost superhuman level, what powerful leaders endure — and more importantly the personal and political failures they often succumb to. As James Shapiro writes, “Shakespeare’s histories and tragedies put leaders under extraordinary pressure—and then turn up that pressure even further, until those leaders fail.” Shakespeare, of all the writers Lincoln had access to, spoke to his incredibly unique position best, a position that, as Lincoln thought, was even more dire than George Washington’s amid the Revolutionary War. And Lincoln, of all of Shakespeare’s readers, was in a position so intense and isolating that he was likely able to understand exactly what Shakespeare was trying to get at, perhaps better than anyone before or since in American history. Lincoln is our national martyr, a seemingly idealistic leader who lived and died heroically by the principles that our republic holds sacred, and his engagement with Shakespeare’s work gives us unique insight into the nearly incomprehensible nature of what he endured. He is America’s ultimate real-life Shakespearean figure, one whose story is so powerful and tragic that it seems equally at home on the stage as in the history book.

Further Reading

Anderegg, Michael A. Lincoln and Shakespeare. University Press of Kansas, 2015.

Boller, Paul F. “The American Presidents and Shakespeare.” The White House Historical Association, 2011, www.whitehousehistory.org/the-american-presidents-and-shakespeare.

Cannon, Le Grand B. (Le Grand Bouton), 1815-1906. Personal Reminiscences of the Rebellion, 1861-1866. New York: Burr Printing House, 1895.

Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln. Touchstone, 1996. Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. https://securegrants.neh.gov/publicquery/main.aspx?f=1&gn=RO-21828-89

Forney, John W. (John Wien), 1817-1881. Anecdotes of Public Men. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1873, 1881.

McClay, Wilfred W. “Lincoln the Great.” HUMANITIES: The Magazine for the National Endowment for the Humanities, vol. 30, no. 1, 2009, https://www.neh.gov/article/lincoln-great. McClay is a former member of the National Council on the Humanities.

Open Source Shakespeare. George Mason University, 2003. https://www.opensourceshakespeare.org/

Paul, Richard L., producer, and Paster, Gale Kern, host. “Men of Letters: Shakespeare's Influence on Abraham Lincoln.” Shakespeare Unlimited, Folger Shakespeare Library, 2009, https://www.folger.edu/men-letters-shakespeares-influence-abraham-lincoln.

Shapiro, James, and Bill Clinton, editors. Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to Now. The Library of America, 2014. The Library of America received $1.2 million in seed money from NEH in 1979.

Shapiro, James. Shakespeare in a Divided America: What His Plays Tell Us about Our Past and Future. Penguin Press, 2020. Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Shapiro is an NEH Public Scholar. https://securegrants.neh.gov/publicquery/main.aspx?f=1&gn=FZ-255906-17

Wilson, Douglas L. “His Hour Upon the Stage.” American Scholar, Phi Beta Kappa, 30 Nov. 2011, https://theamericanscholar.org/his-hour-upon-the-stage/#.XzU30RNKhQI