The Hidden World of Holy Spies: A Q&A with NEH Public Scholar Matthew Avery Sutton

Courtesy Matthew A. Sutton, photographer: Julia Lampe

Courtesy Matthew A. Sutton, photographer: Julia Lampe

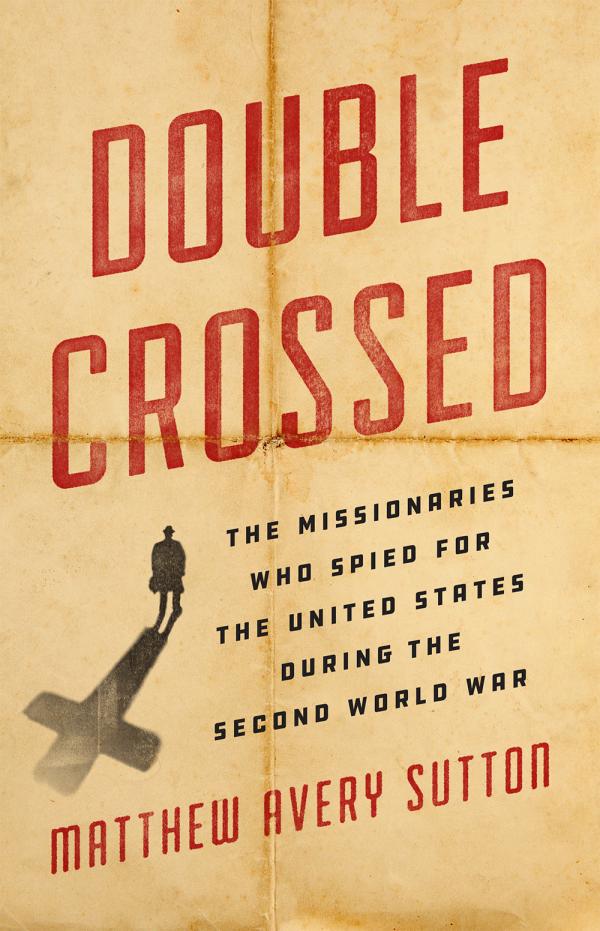

In civics classes across the country, students are taught that a metaphoric wall separates church and state. However, the church-state connection is far more complicated, according to NEH Public Scholar Matthew Avery Sutton. “During the 1940s,” he writes, “American leaders came to understand in deeper and more explicit ways how central religion was to crafting successful foreign policy.” They hatched numerous plans to use spirituality as a political tool, but one in particular stuck: hiring missionaries to “serve God and country” as spies. Sutton’s book, Double Crossed: the Missionaries who Spied for the United States during the Second World War, examines this “holy” espionage throughout WWII, presenting a fledgling U.S. intelligence agency, its religious assets, and their unusually close alliance.

I was able to talk with Matthew Sutton about his project.

1. Double Crossed begins with the creation of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). What was the OSS, and who was William “Wild Bill” Donovan?

Before World War II, the United States had no central foreign intelligence agency, and many American leaders felt ambivalent about spycraft. Herbert Hoover’s secretary of state summed up the traditional American attitude when he allegedly quipped in the late 1920s that “Gentlemen do not read each other’s mail.” By the late 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt knew this was a problem. In the summer of 1941, he established the office of the Coordinator of Information, which he soon renamed the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). He charged the OSS with keeping the White House abreast of the latest developments as war raged in Europe and Asia.

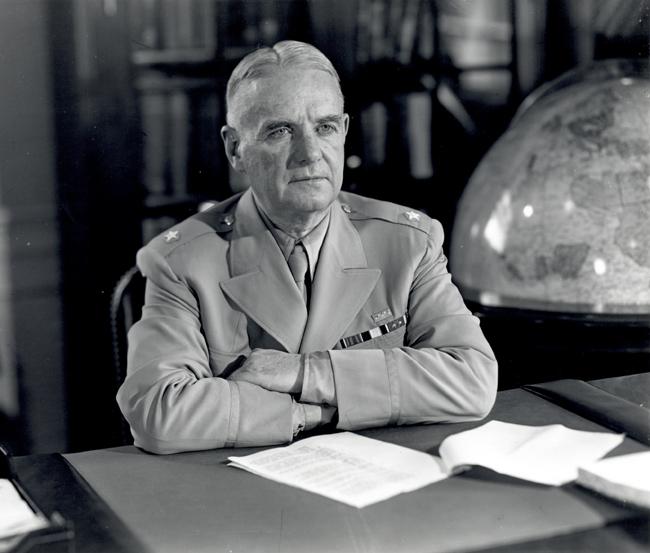

To run the new agency, Roosevelt appointed World War I veteran and corporate attorney William “Wild Bill” Donovan as director. He authorized Wild Bill to collect data for the commander-in-chief and to carry out “such supplementary activities as may facilitate the securing of information important for national security.” What those supplementary activities were the president never explained. The open-ended mandate gave Donovan carte blanche to build a covert intelligence network that operated around much of the world. After the war, the OSS morphed into the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

2. How did Donovan and the OSS come to recruit missionaries? Why did they believe missionaries would make such capable spies?

Donovan and his aides, including future CIA director Allen Dulles, had to scramble to recruit people for the organization. They hired lawyers, labor leaders, businessmen, and flight attendants. They also hired missionaries, priests, and at least one rabbi. Religious activists’ efforts started small, but expanded as they demonstrated their value. OSS officers realized that missionaries made some of the best clandestine operatives. Missionaries have excellent language skills, they understood cultural sensibilities, they knew how to disappear into foreign cultures, and they were masters at effecting change abroad. By the end of the war, American missionaries were gathering intelligence, keeping tabs on Axis agents, drafting plans to infiltrate enemy territory, partnering with insurgent groups, recruiting foreign hitmen, and hatching assassination plots. They also established new partnerships for the United States in the centers of global religious power, including Mecca, the Vatican, and Palestine that helped shape the Cold War fight against “godless” communism.

3. While your book mentions numerous missionaries in espionage, it centers on four in particular: Stewart Herman, William Eddy, John Birch, and Stephen Penrose. Why did you choose these four, and what were their religious backgrounds?

I settled on these four for a variety of reasons. First, I needed people who had left behind a substantial enough documentary record for me to really understand and narrate their stories. Second, I wanted the book to tell the story of the entire war, covering all of its theaters, so that also influenced my choice of characters. Eddy was based primarily in North Africa, Penrose was in the Middle East and Balkans, Birch was in China, and Herman had been in Germany and spent most of the war in London. These four missionary spies allowed me to cover most of the globe.

Their religious backgrounds varied. John Birch was a fundamentalist who believed that World War II was setting the stage for Armageddon. Eddy was a mainline liberal Protestant, Herman was a Lutheran, and Penrose was a Congregationalist. I also tell the stories of various Jews, Catholics, and Muslims who interacted with the OSS and its missionaries.

4. What was work in the field like for Herman, Eddy, Birch, and Penrose? Of these four, did you find one to be more interesting – or daring – than the others?

This really varies from person to person. Herman was working with the German underground to try to penetrate the Third Reich, which was extraordinarily difficult. Eddy was running spies around North Africa and had a lot of early success. He got his hands very dirty early in the war sabotaging Axis agents and plotting assassinations. He was instrumental in Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa. Birch was accustomed to working with the Chinese in the countryside. In the war he served as a liaison between Chinese forces and the American Air Force. He helped pilots select targets and attack Japanese forces. Penrose was mostly involved in recruiting agents in the Middle East and in the Balkans.

Eddy was probably my favorite character because he was about my age, he was very funny, and his love and concern for his family was evident in his work. He was easy to relate to and to root for. He was also the most self-consciously aware of the moral/ethical questions raised by his actions and the most forthright about the contradictions between his faith and his work as a spy.

5. More generally, World War II established the complicated legacy of missionaries who worked for the U.S. government. What do you perceive as their successes and failures?

This is certainly a complicated issue. The missionaries who served during World War II made really important contributions and they had skills that at the time few other Americans could match. But now that we have a professional, sophisticated, well-developed intelligence agency, I don’t think there’s any reason for missionaries to be involved at all in foreign intelligence operations. If one missionary is suspected of working for the CIA in some foreign territory, that makes all missionaries suspect. In my last chapter, I analyze the ongoing debate about the CIA’s policies regarding hiring missionaries and other religious activists.

6. You note how missionary spies often mixed the personal with the professional, and the sacred with the profane. How did you select sources to demonstrate this double life?

For me, this is one of the most important parts of the book. One thing I wanted to do was balance my analysis of these men’s lives as spies with their personal, private, and religious lives. So, in some ways, part of why I chose these four was because they each allowed me to do this. Each person has extensive operational records located in the National Archives from which I drew. And each also has an extensive collection of private papers, including diaries and letters, which were equally revealing. To make sense of what was happening, I had to do a lot of triangulation. I might, for example, know that a particular operation was underway involving one of my agents based on the materials in the National Archives. That agent never discussed such things in letters or diaries, but the letters and diaries are dated, so I would read the different sets of records together to see what my subject was thinking and feeling at the same time he was engaged in a particular operation.

7. While researching these sources, were you surprised by anything you discovered?

In many ways all the research was surprising, which is what made it so fun. Many of the stories I uncovered could have come straight out of James Bond books. There is lots of action and drama and mystery and suspense. The challenge was actually finding those stories buried in the millions of pages of OSS documents in the National Archives. The OSS and then CIA worked hard to cover up this history—beginning with Donovan and Allen Dulles. So it took a good deal of time and patience to locate the relevant records.

8. Why is it important that this narrative – of “holy spies” – be made accessible to the public?

It’s important in a lot of ways. The story demonstrates the role that American religion played in American foreign policy, which is something we do not always recognize or appreciate enough. I think it also helps us understand some of the unheralded heroes of World War II and the kinds of sacrifices they made to help the Allies win the war. But this is also a cautionary tale. For the missionaries themselves, the war was a horrific experience and many regretted the compromises they had to make to ensure victory. The book also offers numerous examples of how religion can be manipulated by the state in wartime, in the U.S. and abroad.

Matthew Avery Sutton is currently writing a book on the history of American Christianity, from colonial times to the present. In it, he hopes to explain how Christianity has developed in and shaped the United States.

Funding and program information

Matthew Sutton received a Public Scholars award (FZ-250439-17) to support research for Double Crossed: the Missionaries who Spied for the United States during the Second World War (Basic Books, 2019).

The Public Scholars program supports well-researched books in the humanities written for the general public. For more information on the NEH Public Scholars program, or to apply, see the program’s resource page. Contact @email with questions.