The Cultural Eco-District: A Collaborative Approach to Climate-Smart Planning

The Bartlett Courtyard, pictured here, is part of the 14-acre urban arboretum, located on the Linda Hall Library’s campus. The arboretum is home to a wide variety of plants, flowers, and trees native to the Kansas City region.

The Bartlett Courtyard, pictured here, is part of the 14-acre urban arboretum, located on the Linda Hall Library’s campus. The arboretum is home to a wide variety of plants, flowers, and trees native to the Kansas City region.

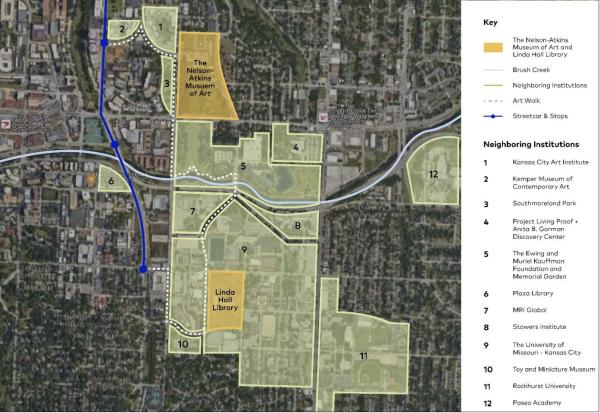

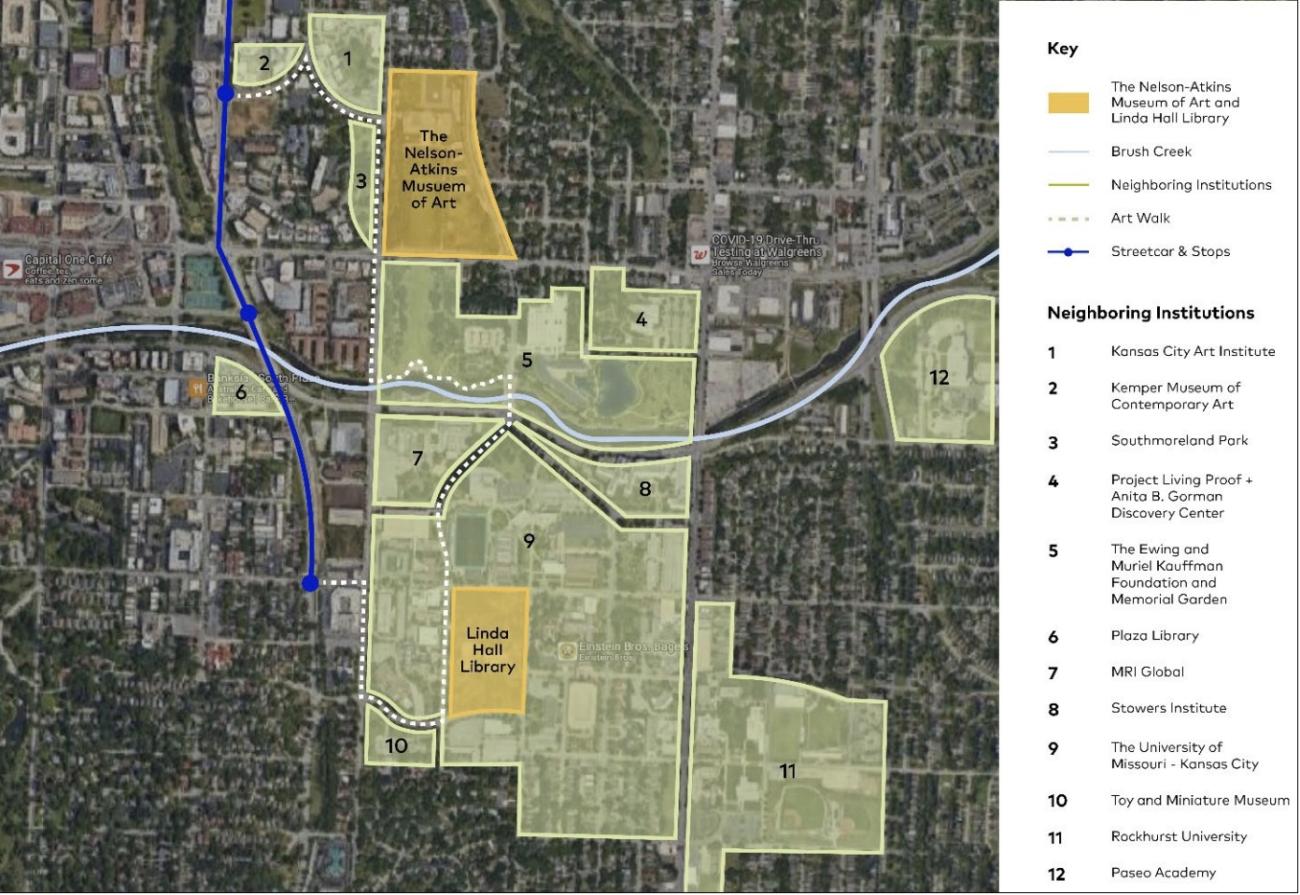

As climate disruption becomes an increasingly prevalent threat, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and Linda Hall Library in Kansas City, Missouri, are championing sustainability efforts through a unique collaboration. Their Climate Smart project includes the formation of what they’ve termed a “Cultural Eco-District,” a geographic area in the center of Kansas City that invites other humanities-driven organizations to work together on climate mitigation and adaptation strategies. By involving other organizations, the Nelson-Atkins and Linda Hall Library are leading their community to develop a broad network that has the power to preserve and sustain both the cultural and environmental heritage of the city.

Historic Collaboration; Future-Oriented Thinking

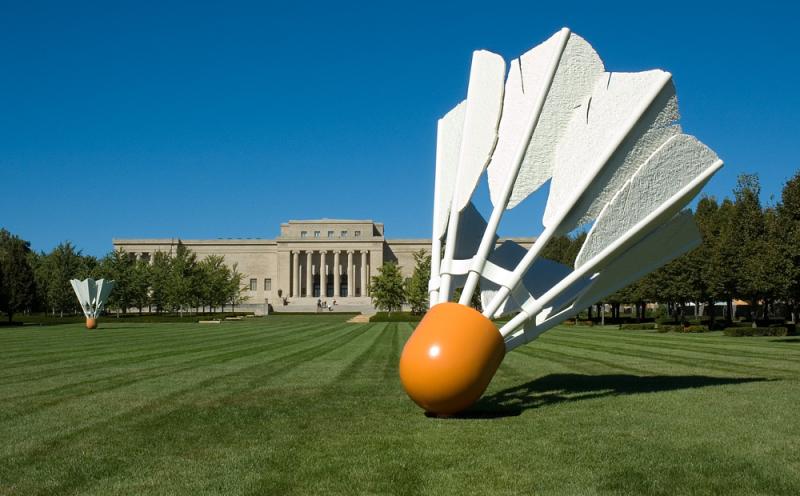

Located just a mile apart from one another, the Nelson-Atkins and the Linda Hall Library are two of the largest and most highly regarded cultural institutions in the Midwest region. The Nelson-Atkins is recognized as one of the finest art museums in the country for its collections, extensive educational programming, and cultural festivals. The Linda Hall Library is an independent science research library that attracts scholars from around the world for its expansive archival collection and is a core fixture in Kansas City, offering free science, tech, and engineering-oriented programming to the community.

In the past, the Nelson-Atkins and the Linda Hall Library have shared ideas as they worked independently on climate initiatives, but this partnership would mark the first time that they work jointly in a climate action project. The partnership promises to bring both organizations even closer to their environmental goals, and staff at both the Nelson-Atkins and the Linda Hall Library have expressed their excitement about the collaboration. Michele Knight, Vice President of Engagement at the Linda Hall Library emphasized that “by working together, we can leverage our resources and expertise to make a bigger impact than we could individually.” Steve Waterman, Deputy Director of Design and Experience at the Nelson-Atkins agreed, noting that both institutions benefit from one another as they explore avenues for environmentally sustainable options.

Waterman and Knight both emphasize the long-term vision of their NEH Climate Smart grant as well. Rather than viewing the grant as a finite project, they see it as a stepping stone toward future climate initiatives. “By thinking beyond the immediate scope, we aim to create lasting change and inspire other institutions to join our mission,” Waterman explained. They intend to share their findings with all partners in the Eco-District to inspire a model for effective climate action throughout the region. “[The Eco-District] facilitates joint programming and enhanced problem-solving capabilities, ultimately fostering a more sustainable future for both institutions and the wider community,” said Waterman. Knight hopes that the collaboration will be “a beacon for other Midwest institutions to acknowledge and address climate change proactively.”

The Environmental Humanities: How Museums and Libraries Engage in Climate Action

The threat of climate change can seem far removed from the historical, introspective worlds of museums and libraries, but engaged, dynamic institutions like the Nelson-Atkins and the Linda Hall Library are proving that humanities organizations can actually be a perfect place to start climate action conversations. Museums, libraries, and similar institutions can serve as an essential bridge in their ability to synthesize complex information and present it to the public. Museums and libraries that function as trusted community partners may be the key to providing accurate, yet digestible information about sustainability and climate to their visitors without imparting a sense of climate doom.

Although climate discussions are not always easy, such shared concerns can also bring people together. The Nelson-Atkins and the Linda Hall Library have both found that their board members, visitors, and partner organizations have rallied behind their climate-based initiatives. They’ve found that local businesses, foundations, and nonprofits are eager to get involved in climate and environment-related events, programming, or exhibitions. “From a fundraising standpoint, [climate action] has become a very compelling narrative,” Knight observed.

Projects that decrease energy consumption are often also more cost-effective, which can be another persuasive way to generate excitement among leadership and board members about environmental initiatives. Waterman commented, “civic leaders are always looking for efficiency and impact, and [the Eco-District] plan will do both.” Regardless of whether stakeholders get involved with eco-friendly projects from an environmental perspective or a financial one, Waterman believes that getting humanities organizations involved with climate action planning is critical: “It will essentially preserve our ability to speak about the humanities into the future.”

Bridging Climate and Culture at your Institution:

The Kansas City Cultural Eco-District exemplifies how the humanities and collaborative thinking are essential elements in environmental advocacy. The links below offer some guidance about how to approach your stakeholders and potential funders, and how to articulate the relationship between the humanities and sustainability:

2. This FEMA document explains how the Arts and Humanities are connected to environmental mitigation.

In 2023, the Nelson-Atkins and the Linda Hall Library received an award through NEH’s Climate Smart Humanities Organizations program to help them adapt and mitigate climatic impacts on their institutions. Together, they are developing a Cultural Eco-District in Kansas City that can be adopted by other humanities organizations throughout the region.