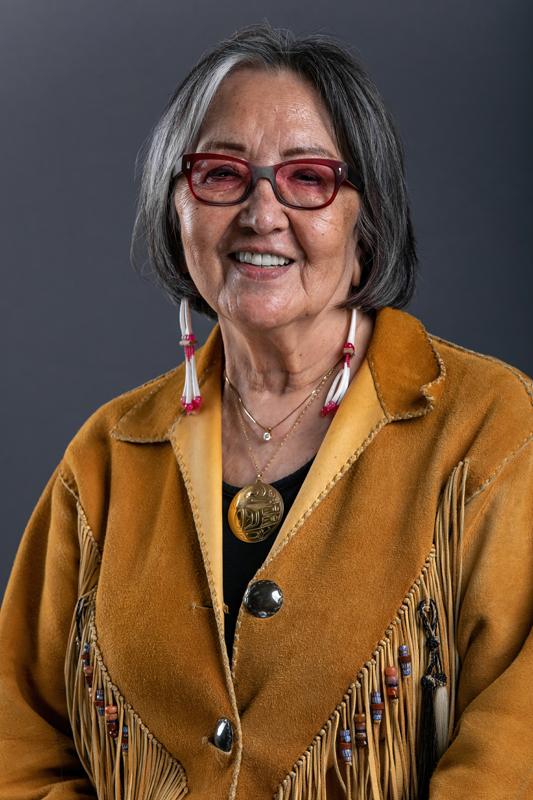

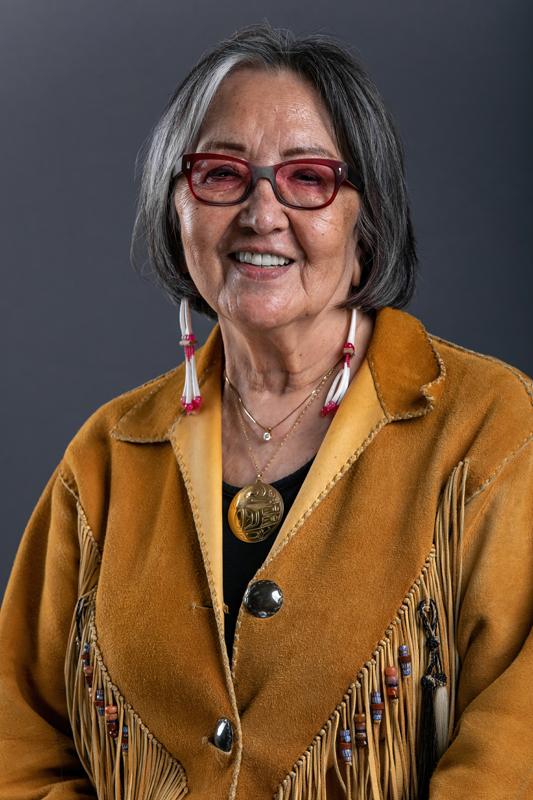

Rosita Worl

National Humanities Medal

2023

—Courtesy Sealaska Heritage Institute

—Courtesy Sealaska Heritage Institute

Rosita Ḵaaháni Worl’s life was profoundly changed when school officials kidnapped her at age six and placed her in a boarding school. Their goal was to “civilize” and assimilate Alaska Native children into white Christian society.

“Not knowing why I was there, and crying at nighttime and wondering where my family was, and then seeing how people hated us—hated the way we looked, hated the way we talked—and being punished, always being punished. . . . The punishment they gave us would be called child abuse today,” she says. Kids were taught to laugh at other kids for speaking Tlingit.

Little did those officials know, their approach honed what became a lifelong determination to preserve her Tlingit culture and language.

Worl grew up and took a job as president of the Sealaska Heritage Institute, which under her leadership has established itself as a model for Native Americans across the country and even around the world in language and cultural preservation.

With its board of trustees, Worl visited a Hawaiian language program. “Our trustees cried when they saw the little ones speaking Hawaiian. So we made it our top priority.”

Worl achieved a doctorate in anthropology from Harvard and has been recognized with many awards but said her proudest moment came as she watched a group of Tlingit children. “Here are all these little munchkins coming in, singing our songs, just so proud. And when I see that, I always say, ‘We will hear the voices of our ancestors,’ and we are now hearing it through our children.”

“I just believe we have such a great culture,” she said. “I mean, we’ve survived for at least 11,200 years ago, from our latest archeological finding. I know we had a great culture that survived climate change, rising [and] lowering of the seas, glacial advances, glacial retreats, and then the suppression of our culture. We survived all of that. So I said, ‘There's something good about our culture . . . and we have to start teaching people about our culture.’ So we do that.”

Sealaska had a staff of six when Worl became president in 1997. Now it has 85 full-time employees. Its budget for language programs has grown as well. Worl says that between developing curricula and training and paying teachers, “just in Juneau alone, probably on an annual basis we're putting around two million (dollars) into the Juneau school district and then into the university system, probably another million.” The institute partners with 45 or so entities throughout the region, Worl says, to achieve its mission.

Every two years Sealaska hosts a Celebration of Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian cultures. Thousands of people attend and dozens of dance groups perform. People take part in workshops and celebrate their cultures with events ranging from a toddler fashion show of traditional clothing to lessons on how to harvest food. The celebration has led to a resurgence of regalia making and singing and dancing in traditional languages.

Sealaska has built a multimillion-dollar arts campus in the heart of downtown Juneau. Its striking architecture makes the center a prominent monument to Native form-line artistry. The institute has also begun developing a trail featuring 30 totem poles that will honor five Native groups of Alaska, the Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Dena'ina, and Alutiiq.

Worl says they are aiming to push “the integration of Indigenous knowledge into not only the education of our younger children, but into decisions that are made by the federal government that affect us.”

Her bio on the website of the First Alaskans Institute, for which she is a trustee, summarizes Worl’s other accomplishments. Worl “has been a professor of anthropology at University of Alaska and authored papers on subsistence ways of life, Native women’s issues, Indian law and policy, and Southeast Alaska Native culture and history. She also served on the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) National Review Committee from 2000-2013, including as its chairperson. She has served on numerous boards and committees, including the Alaska Federation of Natives, the Indigenous Languages Institute, the National Science Foundation Polar Programs Committee, the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission Scientific Committee, and the National Museum of the American Indian.” Worl served on the board of directors for the for-profit regional corporation for southeast Alaksa, Sealaska, for more than three decades.

Eighty-seven years old, Worl continues to work and lead. She perseveres, she says, because her mother taught her to. “I had a responsibility and duty to work for our people, so it was ingrained in me.”

When her mother passed, Worl says that she thought of “all the contributions she left us, and I thought to myself, What am I going to give to my children and my grandchildren?”

—Joaqlin Estus