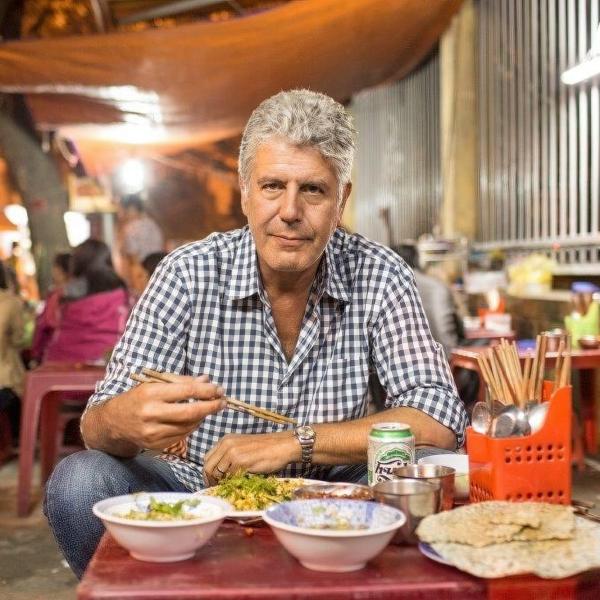

Anthony Bourdain

National Humanities Medal

2023

—CNN

—CNN

Anthony Bourdain grew up in New Jersey in a middle-class home full of books and vinyl records. His father was in the music business. His mother stayed at home to raise her sons, then later took a job as a copyeditor for the New York Times.

The future television star was a reader and a rebellious youth. As a kid, he was bitter, he once told the Guardian, that he had been too young to be a hippie.

In the summer between fourth and fifth grade, the Bourdain family spent the summer in France, where Anthony frequently acted up. His favorite form of misbehavior involved food: To shock his parents, he would eat absolutely anything, including something that turned out to be delectable, a raw oyster just pulled from the sandy bottom of a creek in southwestern France.

“It tasted of seawater . . . of brine and flesh . . . and, somehow . . . the future," he later wrote. "Everything was different now, everything. I’d not only survived—I’d enjoyed.”

After a couple years at Vassar, Bourdain withdrew from college and enrolled in the Culinary Institute of America, graduating in 1978. He worked as a journeyman chef in New York and Europe, training at various high-end restaurants, but he was no culinary star. He described himself as the chef who is brought in after the chef you have hired has turned out to be “a psychopath, or a mean, megalomaniacal drunk.”

It was writing, not cooking, that brought about a major shift in his life and career. An aspiring fiction writer, he once took a class with the legendary editor Gordon Lish and worked his way up to publishing a couple of crime fiction novels whose stories centered on food.

But while the crime novels got remaindered, Bourdain worked on a piece of nonfiction, an essay, talking out of school about his experiences as a chef. The piece showed the restaurant business to be something of a corner-cutting grind just as food culture, with the rise of celebrity chefs and soaring popularity of the Food Network, had come to seem more glamorous and high-minded than ever.

Bourdain’s piece had been accepted at the New York Press, Manhattan’s scrappy downtown alternative to the Village Voice, before being summarily rejected there. His mother gave it to her Times colleague Esther Fein, asking her to show it to her husband, David Remnick, editor of the New Yorker. Remnick warmed to it immediately.

The writing was gritty and direct, profane even. More George Orwell than Joy of Cooking, it focused on the work and economic conditions of restaurant kitchens while explaining why it was a bad idea to order fish on a Monday. The piece was published as “Don’t Eat Before Reading This,” and then widely enjoyed. It’s only so often that a magazine essay seems to have been read by everyone with even a passing interest in the subject, but this was one of those times.

A year later, Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly was published to broad acclaim. A book that lived up to the hype, it introduced a major new voice, by turns thoughtful, comic, lewd, and confessional, but very serious about food.

Even as it played up the misfits who work in the food business, Kitchen Confidential struck a blue-collar note, celebrating the line cook, not the celebrity chef, and featuring busboys, dishwashers, and others working hard and fast. A million copies have been sold.

Bourdain’s first television series was A Cook’s Tour on the Food Network. It contained all the key ingredients of his later, more celebrated television work: a strongly written opening monologue; heavy narration throughout; and exotic locations, whose people and history were thoughtfully referenced and discussed.

“I'm looking for extremes of emotion and experience,” he said in the narration that ran over the beginning montage. As in his writing about restaurants, his television work routinely upended expectations, showing that television didn’t need to avoid context to be compelling.

After two seasons of A Cook’s Tour, the same approach was given an upgrade in Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations on the Travel Channel. The budget had grown, but the idea stayed the same. “I am Anthony Bourdain. I write. I travel. I eat. And I'm hungry for more.”

In early 2018, Bourdain took his own life, to the shock of various people who knew him. It was a blow to his many admirers as well, who had taken heart from his example and his work, which had arrived like a message from another world, praising the act of creating culture and reveling in the pleasures of being alive.

—David Skinner