Women’s trousers have long been a symbol of freedom in the Western world. But the idea commonly associated with women’s trousers—that they were inspired by men’s trousers—is not historically accurate. When women’s rights advocates in Europe and the United States first promoted trousers for women, many of them were pointedly not imitating men. They were imitating other women, Muslim women.

This may sound odd to anyone who believes that the Muslim world, historically, has been uniformly opposed to women’s rights. The true story is more complex.

Dress—what we wear and how we wear it—is often thought of in terms of taste and waste, vanity and frivolity. But dress and textiles are closely involved with economic, cultural, historic, and political patterns. The fashion industry is in constant search of inspiration for new designs, and, as a result, fashionable dress visibly reflects cultural and social events, and shifting values. Though some of the original sources and conversations behind a particular garment may have faded from common memory, the echoes are still there, if you know where to look.

Eastern influences were visible in the dress of European elites going back to at least the twelfth century. The Middle East and then the Ottoman Empire were centers of textile production and held almost total control of the trade between Europe and Asia for centuries. Europeans imported or wove imitations of the luxurious silks, camlets, and brocades of the East. The traditional Turkish aesthetic of layered front-opening coats and jackets with buttons had migrated into European dress through trade and diplomacy and, later, illustrated travel books, starting late in the fourteenth century. But until the late eighteenth century not even European men wore what we would consider trousers. Their lower garments consisted mostly of leg-displaying hose and short breeches in various combinations.

Central Asian men and women, including the original Turks, have, however, worn trousers for three thousand years.

In 1716, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu traveled to Constantinople with her husband, the British ambassador. Until then, only European men traveled to the wealthy and powerful Ottoman Empire, and they were almost never allowed to meet respectable women in private homes. Predictably, they developed lascivious fantasies about harem life that had little basis in domestic reality, and wrote about their fantasies as fact. Their titillating visions have persisted in Orientalist art and literature to this day.

Lady Mary was one of those brilliant wealthy aristocratic women with the will and the means to defy the social expectations of her time. The daughter of an earl, she had mostly educated herself in her father’s library.

She taught herself Latin, wrote poetry and fiction, and used correspondence to broaden her intellectual and social world. A strong-minded and personable beauty, she chose to elope rather than accept the man her parents had chosen for her. When she set off with her husband for Constantinople, she had no particular religious agenda.

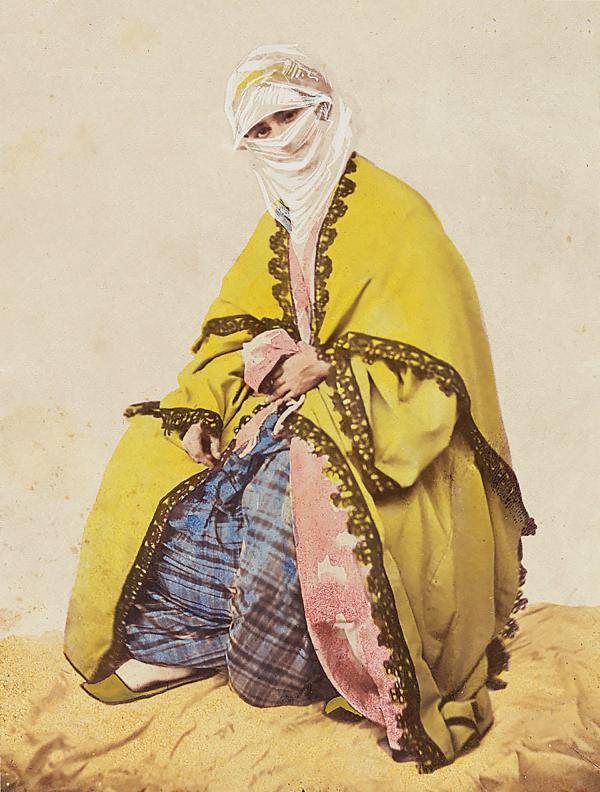

All the same, she became the first European to write an eyewitness account of the daily life, dress, and manners of Turkish Ottoman women. As they traveled to the Ottoman court, Lady Mary and her husband were the guests of an educated Muslim gentleman in Belgrade, with whom she discussed poetry, literature, religion, and the place of women, through her interpreter. Among those who invited her into their Constantinople homes were the wife of a grand vizier and the widow of a sultan. She studied Turkish, and, if one can believe her, became fluent enough to hold direct conversations with Turkish friends. She explored the city, sometimes in the spectacular company of a friend’s French retinue, and sometimes unobtrusively dressed and veiled in Turkish clothing, appropriate to her status as directed by her hosts, wandering as she liked, with one female companion and a Turkish guard. Ottoman manners and life appealed to both Lady Mary’s romantic aesthetics and her practical side. At this time, European court dress resembled armor, corseted and heavy. In contrast, the luxurious and modest but relatively unstructured forms of traditional Turkish dress felt astonishingly free and comfortable.

She wrote to her sister:

I am now in my Turkish habit. . . . I believe you would be of my opinion, that ’tis admirably becoming. . . . THE first part of my dress is a pair of drawers, very full that reach to my shoes, and conceal the legs more modestly than your petticoats. They are of a thin rose-coloured damask, brocaded with silver flowers. . . . Over this hangs my smock, of a fine white silk gauze, edged with embroidery. This smock has wide sleeves hanging half way down the arm, and is closed at the neck with a diamond button; but the shape and colour of the bosom is very well to be distinguished through it.—The antery is a waistcoat, made close to the shape, of white and gold damask, with very long sleeves falling back, and fringed with deep gold fringe, and should have diamond or pearl buttons. My caftan, of the same stuff with my drawers, is a robe exactly fitted to my shape, and reaching to my feet, with very long strait falling sleeves.

She went on to discuss the Turkish women themselves, writing:

As to their Morality or good Conduct . . . ’tis just as ’tis with you, and the Turkish Ladys don’t commit one Sin the less for not being Christians. Now that I am a little acquainted with their ways, I cannot forbear admiring either the exemplary discretion or extreme Stupidity of all the writers that have given accounts of ’em. ’Tis very easy to see they have in reality more Liberty than we have, no Woman, of what rank so ever, is permitted to go in the streets without two muslins, one that covers her face all but her Eyes and another that hides the whole dress of her head and hangs halfe way down her back; and their Shapes are also wholly conceal’d by a thing they call a Ferigée, which no Woman of any sort appears without. This has strait sleeves that reaches to their fingers ends and it laps all round ’em not unlike a rideing hood. In Winter tis of Cloth, and in summer plain stuff or silk. You may guess then, how effectually this disguises them, that there is no distinguishing the great Lady from her Slave, and ’tis impossible for the most jealous Husband to know his Wife, when he meets her; and no Man dare either touch or follow a Woman in the street.

This perpetual Masquerade gives them entire Liberty of following their Inclinations without danger of Discovery. . . . Neither have they much to apprehend from the resentment of their Husbands, those Ladys that are rich having all their money in their own hands, which they take with ’em upon a divorce with an addition which he is oblig’d to give ’em. Upon the Whole, I look upon the Turkish Women as the only free people in the Empire.

British married women would not have comparable rights over their property for over 150 years, until the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882. White women in the United States would slowly win comparable legal rights, state by state, through the course of the nineteenth century.

Lady Mary’s friends passed her letters around, and they became a popular sensation. When she returned to England, her essays on marriage and women’s education circulated among her friends, and a few were published anonymously. At times she still wore her Turkish clothes, and posed for public portraits in them. After her death in 1762, her letters were formally published, and her descriptions helped inspire a craze for Turkish-inspired fashions.

A Muslim visitor to England between 1800 and 1803 corroborated Lady Mary’s cultural comparisons. He disapproved of many aspects of English women’s behavior, but noted that they were more restricted in their movements, could not go out after dark, had no property rights, and were at a disadvantage compared with women in his own country.

Other British women published similar memoirs in the nineteenth century. Some of them glossed over or romanticized the genuine educational and religious disadvantages faced by Ottoman Turkish women, but the legal, marital, and social freedoms they noted were real.

In 1838, the British traveler Julia Pardoe wrote:

It is the fashion in Europe to pity the women of the East; but it is ignorance of their real position alone which can engender so misplaced an exhibition of sentiment. . . . They are permitted to expostulate, to urge, even to insist on any point wherein they may feel an interest; nor does an Osmanli husband ever resent the expressions of his wife.

In 1878, Fanny Janet Blunt, who grew up in the Ottoman Empire, wrote:

I have seldom met with [a Turkish woman] who did not make use of her liberty; in one sense she may not have so much freedom as Englishwomen have, but in many others she possesses more. In her home she is perfect mistress of her time and of her property, which she can dispose of as she thinks proper. Should she have cause of complaint against any one, she is allowed to be very open spoken, holds her ground, and fights her own battles with astonishing coolness and decision. . . . [S]hould a lady possess any property the husband cannot assume any right over it, nor over any of the rest of her belongings.

For most fashionable Western women of the 1840s, skirts were full and floor length, sleeves long, necklines high, and corseting severe. Voluminous shawls, and face-obscuring bonnets, made them almost as modest in their public dress as Turkish women, though more likely to trip. But more of them were becoming educated, and questioning their restrictions. The women’s rights movement included calls for dress reform, for the sake of both freedom and health.

One of the names most associated with those calls, was that of Amelia Bloomer. She lived in Seneca Falls, wife of the postmaster and also his deputy. She organized a women’s discussion group that met in the post office, and became founder and editor of The Lily, the first newspaper for women in the United States. A well-known writer and public speaker, she headed many committees, attended many conferences and conventions, and introduced her friend, neighbor, and regular contributor Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Susan B. Anthony. But she has mostly been remembered for the shaming she received in the international press for her promotion of a style of rational dress that was invented by someone else.

In 1849, an anonymous rural reader wrote a letter to a progressive health magazine, the Water-cure Journal, in which she described the eccentric walking outfit she had put together:

Stout calf-skin gaiters; white trowsers made after the Eastern style, loose, and confined at the ankle with a cord; a green kilt, reaching nearly to the knees, gathered at the neck, and turned back with a collar, confined at the waist with a scarlet sash tied upon one side . . . a green turban made in the Turkish mode. With such a dress I can ride on horseback, row a boat, spring a five-rail fence, climb a tree, or find my way through a greenbrier swamp.

Two years later, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s cousin Elizabeth Smith Miller visited Seneca Falls in a similar ensemble. To early women’s rights activists, Turkish trousers seemed like a promising alternative for respectable ladies. Turkish women were portrayed in popular Western culture as more docile, modest, and cloistered than white Christian women, and their trousers had a soft curving shape that distinguished them from the straight-legged trousers of men. Stanton adopted these garments, and so did many of her friends, including Amelia Bloomer. Bloomer published photographs of herself in this outfit, wrote about it, and provided instructions for making it.

A woman author in the Water-cure Journal wrote:

The costume popularly called the “Bloomer dress,” which is a modification of the Turkish style, has been received with general favor in various parts of the country. . . . The characteristic points of the Bloomer dress are the Turkish pantaloons and short skirt. . . . the pantaloons must be full and tied at the ankle; high boots cannot be worn. . . . Pantaloons adapted to boots must necessarily be cut in the masculine style; and it is easy to imagine how stiff and ridiculous they would look, peering out like a pair of stove-pipes, from beneath a voluminous skirt.

The national and then international press took notice. Suddenly, the “pantaloons” were “bloomers,” and Bloomer was swamped with vitriolic opinion pieces and cartoons. Most of them mentioned “Turkish” dress, and the heathenish aspect seems to have inflamed critics. The contradictory symbolism inherent in wearing Turkish trousers was familiar to both sides of the debate over women’s rights. While to the suffragist it stood for liberation and social equity, to a conservative Christian opponent of reform, the wearing of Muslim dress was in itself something close to blasphemy and a symbol of depravity.

In addition, a similar form of dress had been adopted by women’s auxiliaries to military units, first in Europe and then during the American Civil War. These women, referred to as vivandières or cantinières, acted as field nurses, provided laundry and mending services, and sold food and liquor to the soldiers. However useful they were in the field, this was not a respectable occupation, and their dress was not something that a conventional lady could adopt, no matter how comfortable or practical it was, or how strongly they might support the women’s rights movement. Skirts were the only decent lower garments for Christian women. Two-legged garments, no matter how leg-concealing, were the province of Christian men. Bloomers marked any woman who wore them as an ugly, masculine, blasphemous, cigar-smoking, unpatriotic, free-loving feminist.

After a few years of printed insults and street harassment, Bloomer and her friends decided that the comfort was not worth the trouble. Also, hoopskirts came into fashion, and were much lighter, and easier to manage hands-free, than the earlier, heavy entangling styles.

Women would also wear “men’s” trousers in various contexts, for practicality and to express gender equality and alternative gender identifications. But the mainstream fashion world ignored them almost completely throughout the nineteenth century. Toward the end of the century, as the next generation of suffragists were gaining ground, bloomers reappeared as athletic and beach wear.

Before and during World War I, a well-known surge in exoticism in fashion was widely attributed to a new influx of Eastern design influences. The Ballets Russes toured to the fashion capitals of Paris and New York, and triggered another wave of Orientalism with their opulently costumed ballets created around themes drawn from Asian and Middle Eastern origins. Paul Poiret, in particular, was inspired by the gorgeous spectacles of the Ballets Russes to create revolutionary new forms of women’s dress. He began to examine modes of untailored traditional dress from Turkey, Russia, China, and Japan, and to make use of their fundamental forms. This design vision differed from the more limited, superficial arrangements, ornamentation, or materials that marked most exotic borrowings in the past. One of his inventions was the “jupe-culotte,” or “jupe-pantalon” or “Zouave pantalon” or “trousers-skirt” or “harem skirt,” all of which were names used in a 1911 Vogue article, “The Distracting Jupe-Culotte: Actresses, Lawyers, Social Leaders and Couturiers Express Themselves on the Subject.” It refers to “the present crisis in women’s dress. The fact that the threatened mode savors strongly of the already warmly contested suffrage movement, does not lessen the interest which the subject has aroused among fashionables, and even unfashionables.”

One couturier offered a version described as “baggy trousers joined by a panel of cloth” (which sounds very much like Turkish şalvar), while another garment comes with a “draped overskirt which conceals the objectionable culotte almost entirely from view.” The author comments that “the harem fashion which is stirring continents has spared us for the present the spectacle of Turkish colors upon our Western streets.” She describes an exhibition of Parisian women skaters “dressed à la Turque,” one model in a “distressing . . . harem costume, which escaped the ankles by six or seven inches . . . accompanied by a blue silk turban.” But, alas, “unanimous derision greeted these unaccustomed costumes as they appeared,” a response that would be all too familiar to the women who wore Bloomer costumes sixty years earlier.

But Poiret’s reconsideration of fashion’s basic design and construction vocabulary would continue in the work of many designers, particularly throughout the first half of the twentieth century. The growing rejection of the corseted silhouette challenged designers to find creative ideas based on the new unfitted styles that appealed to increasingly independent and athletic Western women. Women’s suffrage was achieved between 1917 and 1920 in most of Europe and North America. As women achieved more political power, they eagerly abandoned the tightly corseted, long-skirted traditional forms of dress. Then, in 1922, the sensational discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun sparked a mania for anything relating to Egypt. The Egypt portrayed in popular illustrations and films was a fictionalized mélange of ancient Egyptian imagery blended with large doses of standard Orientalist fantasy about the more recent Middle East.

In the twentieth century, this broadening array of borrowings and innovations combined with greater economic, reproductive, and social freedoms for women, meant that all forms of trousers, often indistinguishable from those of men, gradually became part of mainstream women’s dress. There are still some communities where women’s trousers are rejected, sometimes on the authority of the same Bible verses that were thrown at Amelia Bloomer and for the same reason: Women’s trousers retain an aura of feminist liberation that Lady Mary first felt, changing clothes in Constantinople.