“I would see bands, six-piece bands, playing on trucks during my era there, and never see their faces again.” —Danny Barker on growing up in New Orleans

A little over a century ago, Joseph “King” Oliver, mentor to a wide-eyed teenager named Louis “Dipper” Armstrong, stood peering up the main track of New Orleans’ Union Station on South Rampart Street. The Chicago-bound Illinois Central trains hissed, waiting to move. Oliver, a big, well-fed man, couldn’t wait to move either, so tired was he of having to apologize. He led one of New Orleans’ hottest bands, and he had been busted, again.

The arrest happened on June 19, 1918, when Oliver was gigging with his trombonist friend Kid Ory at the Winter Garden, a newish venue at South Rampart and Gravier streets. South Rampart, the bustling main stem of black New Orleans, had been bustling more than usual in the last year, ever since the U.S. Navy shut down the Storyville District, that notorious den of prostitution, drugs, and hot music. This left more than a few District musicians on the street—with one more reason to abandon the South.

Since World War I, a great stream of black Americans had already begun leaving beaten-down lives in “this cursed south land [where] a negro man is not good as a white man’s dog,” as a black man from Mississippi put it. By 1930, in what became known as the Great Black Migration, hundreds of thousands of African Americans had moved north and begun enjoying a new sense of freedom.

“At one point,” notes the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Isabel Wilkerson, “ten thousand were arriving every month in Chicago alone.” Chicago’s South Side, with its increasingly self-reliant African-American culture, became a shining port of call. New Orleans musicians, Joe Oliver included, were taking note.

Oliver’s arrest said a lot about evolving black status in New Orleans, as tensions rose and fell from one neighborhood to the next. Up a block from the Winter Garden, at Saratoga and Gravier, stood the Pythian Temple office building, called at the time the “Eighth Wonder of the world . . . dedicated to the living and built by Negro brains and Negro capital.”

According to the National Park Service, Pythian Temple clients represented “a cross-section of New Orleans black middle and upper classes.” The seven-story building—brainchild of a former slave—brought in black entertainment to perform on its well-known roof garden. Patrons included mixed-blood Creole “Downtowners” raised with some privilege, not used to associating with what one Creole called “cut up in the face” Uptown blacks or their bootstrap music. Yet it was ultimately that musical mélange of Downtown versus Uptown—pedigreed versus self-taught—that cooked up the Crescent City jazz gumbo.

In any case, half a century after Emancipation, black folks wanted position, especially following the Jack Johnson heavyweight victory five years earlier and the racism shown in the recently released Birth of a Nation. They may even have begun to reject the new, blues-inflected “ratty” music, which recalled too much of the “old country,” the plantation. They wanted to join a new century.

But that bluesy, bootstrap music had brought freedom and community. As the old-timers had it, almost anybody could “jump” on a tune. Out there on the street, anyone could make a noise and get people dancing. “No music, you understand, we didn’t know what a sheet of music was,” recalled the bassist Nat Towles. “Just . . . half a dozen men pounding it out all together, each in his own way and yet somehow fitting in all right with the others. It had to be right, and it was, because it came from the right place.”

As Oliver’s friend Pops Foster recalled, “The bands that couldn't read made the most money and were the biggest talk of the town. They were the gutbucket bands like Ory’s band and for a while Dusen’s Eagle Band. They played hot all the time.”

On this June night, the Ory-Oliver band, which Louis Armstrong called “one of the hottest jazz bands that ever hit New Orleans,” apparently made a noise—and customers began abandoning the Temple roof for the Winter Garden. This is when, Ory recalled, Pythian Temple management “called the cops.”

Oliver himself had come up in traditional brass bands but then leaned toward the new “hot” music, beginning with his matriculation into the gutbucket Eagle Band, probably around 1908. Later, after playing the district with his Magnolia Band, he joined the top-line Onward Brass Band under the Creole Manuel Perez. (One observer wrote that when the Onward “played a march, dirge, or hymn it was played to perfection—no blunders.”) Yet even in that rarefied company, Oliver began playing “monkeyshines,” improvised figures around the score. He straddled the Uptown/Downtown fence.

There were likely a couple reasons. First, like any Crescent City musician, he needed to cover all styles and repertoires, especially to follow new trends and suit an international audience. Second, more than anything, he wanted to be a “band man.” He needed camaraderie.

They all did. As Armstrong recalled years later, the musicians he knew from New Orleans were “plagued by feelings of inferiority so crippling that they could not succeed professionally.” For Oliver, the police raid amounted to one more loss in a world loaded with them. One more reason to go down in the mouth, to give up hope. Or to move north, like so many others.

But the Ory-Oliver band had been making gigs all around town, playing the new celebratory music with a solid kick and a “low down, slow” blues, recalled their clarinet man, Johnny Dodds. “They would really moan it out,” Dodds remembered. Adding to this orchestral blues was Joe Oliver’s “talking horn” delivery. With his shapes and slurs, Oliver could converse without words. It would become his signature Chicago sound.

So why the raid? For one thing, Progressive Era reform was taking hold. New anti-vice and prohibition laws were appearing, and the Pythian Temple management may have co-opted them to undercut the upstart Winter Garden.

Yet a larger motive may have ruled. Around this time—more than two generations after Emancipation—Uptown and Downtown musicians were dropping the old divisions. Younger Creoles were jettisoning the “stiff-backed” brass band ways and taking up a new, shuffling dance music, which brought many colors together and threatened established protocol.

As John McCusker has written, “Ory’s group regularly featured both Creole-trained, reading musicians, like Emile Bigard, Manuel Manetta and Johnny St. Cyr, and gutbucket players like Johnny Dodds, Mutt Carey, and Louis Armstrong. In this context, the old labels lost their significance.”

Underneath it all could be heard the beating against Jim Crow and the shout for freedom. As Gary Krist has described in his Empire of Sin, “Jazz was, in a very real sense, an expression of defiance, a projection of black male power that rebelled against the increasing efforts to marginalize and suppress the race. As such, it was viewed as a threat not just to respectability but to the entire social order that was being reasserted in the post-Reconstruction South.”

To Oliver, who played his cards close to the chest, the new black male “power” emerged in his joy at playing. Dr. Edmond Souchon heard him live in a District dive: “At Big 25,” Souchon remembered, Oliver’s band “was hard-hitting, rough and ready, full of fire and drive. . . . It was rough, rugged and contained many bad chords. There were many fluffed notes, too. But the drive, the rhythm, the wonderfully joyous New Orleans sound was there in all its beauty.”

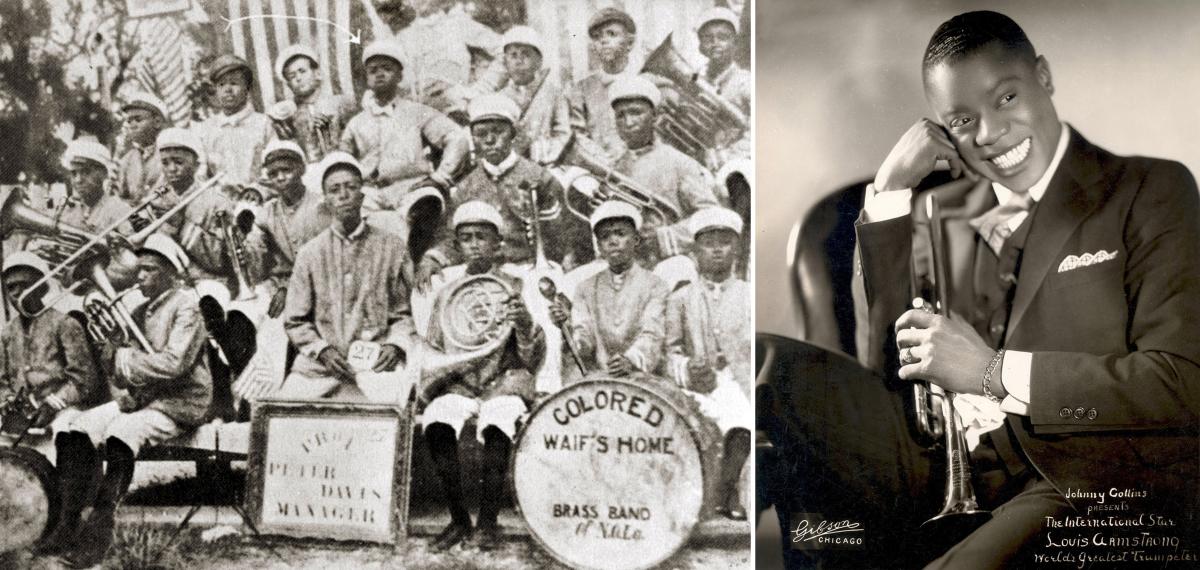

Yet, as Wilkerson has noted, “Across the South, someone was hanged or burned alive every four days from 1889 to 1929.” Oliver, with a second arrest one year earlier, now had a rap sheet. His New Orleans future stood on shaky ground. Nor was he alone. Beginning in the early teens, his protégé-to-be “Dipper” Armstrong had been picked up for pilfering newspapers, stealing from scrap piles, and shooting off a gun. One of Dipper’s running buddies, Henry Rene, was also arrested and placed with Dipper in the New Orleans Colored Waifs’ Home for Boys. (They would later vie in cornet competitions.)

In the clubs, harassment and racism awaited even successful musicians, as Johnny Dodds learned. As Gene Anderson wrote in American Music, “The regular bandsmen took turns collecting the tips, something Dodds . . . disliked because he did not have the ‘gift of gab’ to counter the insults and gibes made by the white customers.”

It was no wonder that black folks were flocking north. Between 1910 and 1920, they would more than double Chicago’s African-American population. World War I and the Chicago Defender would bring thousands of black immigrants who saw a chance to get out from under the white man’s boot and find a better life, with steady, decently paying jobs in the railroad, meat packing, and steel industries. The South Side began booming with new music and dance venues; it offered black folk a chance for release and to live in community among themselves.

And it wouldn’t be long before the immigrant New Orleanians began upstaging the Chicago players. When Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, with Armstrong on second cornet, started at the Lincoln Gardens Café on Cottage Grove Avenue, up-and-coming white players—Benny Goodman, Paul Whiteman, Bud Freeman, Jimmy McPartland, and others—sat way down front near the band, their mouths hanging open, baby alligators waiting to feed on Oliver’s wrapped-up, exploding sound. Recalled the Chicago string man Eddie Condon, “It was hypnosis at first hearing.”

After the Winter Garden bust, Joe Oliver knew it was time to leave New Orleans. Seeing better job prospects, Crescent City musicians had actually begun heading to Chicago six years earlier, when Pretty Baby composer Tony Jackson moved north. Jelly Roll Morton made the trip two years later, in 1914. Then, in the fall of 1918, Joe Oliver received offers from two bands of New Orleans hometown boys who had hit the Windy City—Bill Johnson’s New Orleans Creole Band and Lawrence Duhé’s New Orleans Creole Jazz Band—playing venues that each accommodated around 800 dancers.

Oliver didn’t miss a beat and signed on with both bands, becoming, as the producer Walter Melrose recalled, “the most important musician in Chicago between 1921 and 1930.”

“He never came back,” his wife, Stella, later mourned.

There was irony to Joe’s train departure. He had grown up near Donaldsonville, Louisiana, on the River Road Salsburg sugar plantation, where he lived amidst a 240-car rail system used to transport crops. That system connected to the larger Texas & Pacific Railway and to a world beyond the South.

He would have heard clanking train cars and men pounding tracks, singing in rhythm. Later, in New Orleans, he heard the hammering work song of Mississippi River dockworkers and railroad men, expressions of “intense feelings as they were experienced by the whole group moving together in common purpose,” as Frederick Douglass once described it. Joe Oliver had heard song transform hard labor into freedom—the juice of jazz. Now here he was again, on that train.

A generation after the Winter Garden bust, after practicing for years to perfect his tone, playing endless one-night stands, bringing speech to the jazz sound, losing his teeth to pyorrhea, getting stranded between venues, getting cheated by bookers, and losing his wife to the road, Joe Oliver played on, grinding it out in dance halls all over the South and Midwest.

In 1938, he died, broke, sick and alone, in a Savannah back room, just after his protégé Louis Armstrong had played the 2,145-seat Savannah Auditorium—using his mentor’s old sidemen. But as Oliver had written to his favorite sister, “Look like every time one door close on me another door open.” To this day one can hear Joe Oliver’s talking horn inflections in the work of any authentic jazz musician.

Oliver’s road band colleague Joe Turner recalled, “I clearly remember that on some nights Joe Oliver played so great that outside of Louis Armstrong, I have never heard a trumpet player blow such powerful and beautiful stuff. I realized right then why they called him King Oliver.”