In 1970, 20 percent of all girls participating in high school sports across the country were in Iowa—quite remarkable, considering Iowa was only 1 percent of the entire U.S. population. By 1976, a few years after the passage of Title IX, that eye-popping 20 percent fell to 5.8 percent.

It wasn’t that Iowa girls were playing less, but everyone else was playing more, their access to sports forever changed by federal law. Title IX, which was passed by Congress in 1972, would also change the rules, dynamics, and celebrity culture that had set Iowa girls’ basketball apart for most of the twentieth century.

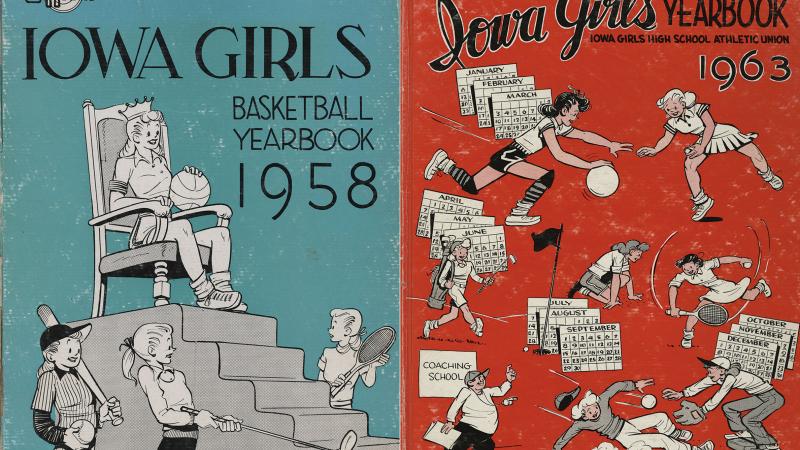

Since the early 1900s, girls’ basketball has been played in Iowa. The first official state tournament was held in 1920, made up of teams of rural players whose families and small towns supported their athletic achievements with enthusiasm and pride. The idea that girls—who worked hard daily on their family farms—were too delicate to play sports wasn’t considered. “I thoroughly believed whatever sport it was, if you surrounded the Iowa girl with respect and prestige, she will in turn give to the viewing audience the very best and finest performance her ability will allow,” said E. Wayne Cooley, the head of the Iowa Girls High School Athletic Union from 1954 to 2002, in an interview for More Than a Game: 6 on 6 Basketball in Iowa, which aired on Iowa Public Television in 2008.

Girls’ basketball was different from boys’: The girls played a type of half-court game with three forwards and three guards on each side who could not cross the center line, could have only two dribbles, and had three seconds to pass or shoot the ball. While boys and girls played 5-on-5, full-court basketball around the country, the 6-on-6 girls’ game dominated high school sports in Iowa. “They had the market cornered,” says Jennifer Sterling, a lecturer in the department of American Studies at the University of Iowa and a speaker on girls’ 6-on-6 basketball for Humanities Iowa. Sterling has been doing research and collecting oral histories on the game, working with the Iowa Women’s Archives at the University of Iowa.

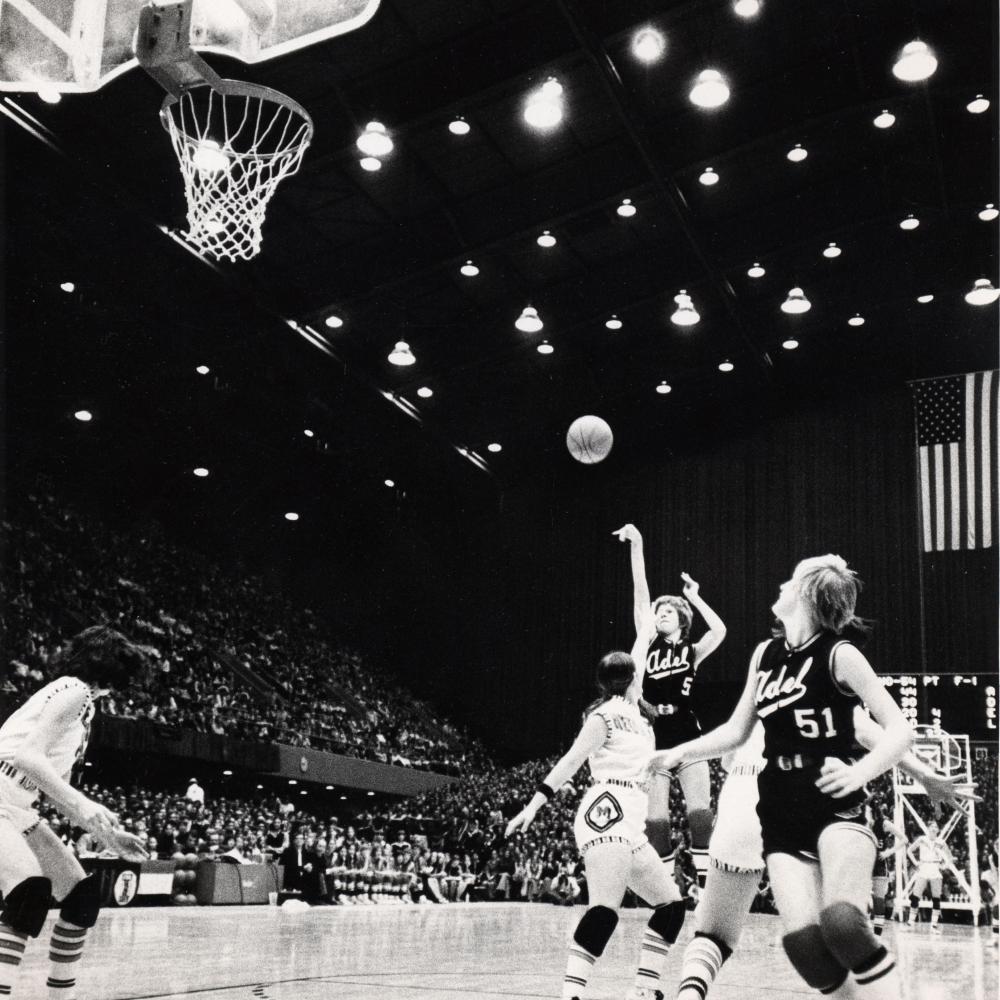

Certainly there were other girls’ high school sports being played in Iowa—track, volleyball, softball. But basketball was the queen, literally. At the annual weeklong state tournament in Des Moines, called the Sweet Sixteen because only the 16 top teams regardless of school size would compete, one exceptional player was crowned queen. By 1955, an elaborate parade of champions introduced all the players of the tournament to sold-out crowds in Veterans Memorial Auditorium—which held almost 16,000 people—with a background of pop music, light shows, dancers, and bands. Men in tuxedos elegantly swept the court at halftime. “It was something Meredith Wilson could have done a great musical about—girls’ basketball,” said Jim Zabel, who began covering Iowa girls’ basketball for WHO radio in the 1940s, in More Than a Game.

“The thing that made the girls’ tournament so unusual was what I always called the marginal audience,” said Cooley. “They’re the people that bought their tickets far in advance so they could have a seat. They didn’t know who they were for, and they didn’t even care. They just wanted to be there.” The final game and hoopla were televised across nine Midwestern states for all the fans who couldn’t score a ticket. CBS sportswriter Heywood Hale Broun called the tournament “sport at its best; full of joy and zest and excitement and a kind of nobility.”

Some girls emerged as legends from their performances at the tournament. People still remember names of standouts like Deb Coates of the 1973 Mediapolis Bullettes, whose profile in Sports Illustrated and Teen Magazine spurred boxes and boxes of fan letters. Or Kim Peters, a one-handed guard from Andrews’s 1976 team, who recalled, “Years later, I mean 20 years later, people would come up and say, ‘I remember when you were captain of the all-tournament team.’” Lynne Lorenzen of Ventura’s 1987 championship team had strangers say to her, “You’re that girl that plays in the barn,” as her story had been told. Lorenzen still holds the title of all-time leading scorer for girls’ high school basketball nationwide, with 6,736 career points to her name. She took that title from Whitten-Union’s Denise Long, who finished her high school career in 1969 with 6,250 points and made history as the thirteenth draft pick for the NBA’s San Francisco Warriors, the first woman ever drafted to play on a pro men’s team.

The Mount Vernon Community Center was the first venue to host “6-on-6 Basketball and the Legacy of Girls’ and Women’s Sports in Iowa,” a traveling exhibit developed by Sterling with Kären Mason, curator of the Iowa Women’s Archives. Six-foot forward Kim Benesh was a junior on the 1984 Mount Vernon squad that went to the Sweet Sixteen, the first team from that town to make it to the tournament. Nearly the whole town followed them to Des Moines, and school was closed for days. “I like that the boys couldn’t play our game,” Benesh says. “I never felt like we were playing a lesser sport, just a different sport. We were more successful and just as competitive.” But Benesh admits it was time to transition; she played on the last 6-on-6 team for the school in 1985.

For most of the twentieth century, rural communities and small schools had dominated girls’ sports in Iowa. Girls in Iowa’s urban areas were not offered the same athletic opportunities until Title IX’s mandate worked its way to girls’ sports around 1976. In 1983, three girls (ages twelve, thirteen, and fourteen) filed suit against the state, claiming that the 6-on-6 game was not equal to the boys’ game. To avoid a legal fight, the league compromised, letting each school choose which game to play and offering two separate tournaments. “It was a school-by-school choice, at first,” says Sterling, “and the first year only 24 teams switched. But they lost support for the modified game.” More and more schools chose 5-on-5, believing it offered the players more college and scholarship options. The last 6-on-6 tournament was held in 1993. “The pressure that we could not handle came from the girls themselves,” said Cooley.

When asked how she felt after learning about the end of 6-on-6, Coates confessed, “It really broke my heart because . . . it was our own brand, our own style of basketball and there was a lot of strategy with it. . . . That’s what happened and so it’s done, but, yeah, it did break my heart.”