The Mississippi river town of Kaskaskia was a frontier boomtown, playing an important role in the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. When Illinois was admitted to the Union in 1818, it became the first state capital. Then, the Mighty Mississippi, Kaskaskia’s source of prosperity, turned on the town, swallowing most of it up. The force of the river cut the remaining land into an island located now on the western side of the Mississippi, the only part of Illinois with this geographical distinction. This once prosperous seat of government and commerce now has fewer than 25 residents and is accessible only through Missouri.

“Kaskaskia has this long-term, multifaceted, multiethnic impact on the entire region and the entire state. It’s significant in various ways today, and yet, it’s not there,” says Matt Meacham, program manager for statewide engagement with Illinois Humanities, who wrote and narrates the video Kaskaskia and the Pursuit of a More Perfect Union Part 1, which can be found on YouTube.

In 1703, members of the Kaskaskia tribe and French Jesuits settled the land near the confluence of the Kaskaskia and Mississippi rivers in Upper Louisiana, also called the Illinois Country. The relationship between the two groups had begun about 30 years earlier when French fur traders visited the territory to exchange goods and married Kaskaskia women, notably the chief’s daughter, Marie Rouensa, who married a prominent trader and became a devout Catholic. The Jesuits established the Mission of the Immaculate Conception in Kaskaskia, and, in 1741, King Louis XV gave a large cast bell to the mission. The inscription read, Pour l’église des Illinois par les soins du roid’outrel’eau (For the Church of the Illinois, by gift of the King across the water). The 650-pound bell was shipped from France to New Orleans and then pulled up the Mississippi River.

Unlike many towns in French North America, Kaskaskia was mostly self-governed by Jesuits and Kaskaskia chiefs. “No official had instructed or even authorized the priests and roving traders to commingle with the Illinois Confederacy, migrate southwest, and start a village. They just did,” says Meacham. Even after the settlement was eventually separated into two villages, Indian Kaskaskia and French Kaskaskia, the two groups freely interacted with each other socially and commercially.

Kaskaskia quickly became a nexus of trade. Wheat grew abundantly in the alluvial soil. Kaskaskia’s mills, two owned by the Kaskaskia tribe and one owned by the French, shipped tons of flour down the Mississippi to New Orleans, earning the reputation as the breadbasket of French America. Vegetables, meat, salt, furniture, and furs were also traded for manufactured and imported goods.

“There was a lot of economic activity in Kaskaskia during that period. By the standards of frontier North America, it was a prosperous community,” says Meacham. “[Although] some of that prosperity was a result of involuntary labor.” In fact, he says, Kaskaskia’s farmers grew so reliant on involuntary labor that by 1750, enslaved Africans accounted for a third or more of the village’s population. The role of African Americans in the region is featured in Part 2 of the video series, which was released on November 17, 2022.

In the 1760s, the economic tide began to turn. The Jesuits were expelled from the region and, at the end of the French and Indian War, France ceded its territory east of the Mississippi to Britain.

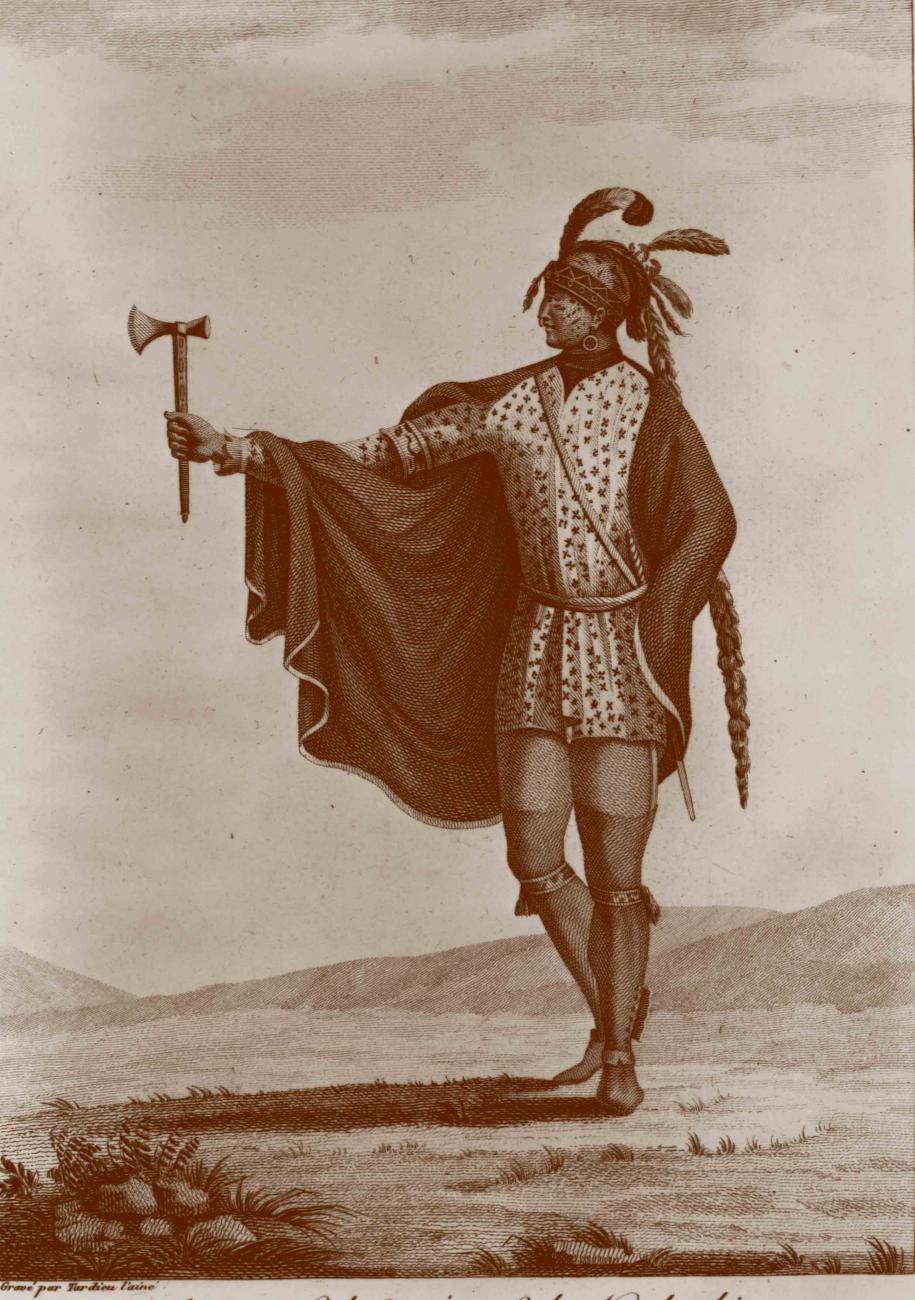

“There’s a very different relationship that the French had with Native groups versus the British or the Americans, because the French looked at a lot of these relationships as, to a sense, transactional in nature,” says Logan Pappenfort, curator of anthropology of Dickson Mounds State Museum, and a descendent of the Piankeshaw tribe. “It’s a commerce exchange, essentially, but once the French are leaving and the Americans are coming in, then it’s a competition for land, and that is when the conflict really starts to escalate.”

Under British rule, Kaskaskia’s population decreased substantially. Many moved across the Mississippi to present-day Missouri. Then on July 4, 1778, George Rogers Clark and his Kentucky Long Knives militia seized Kaskaskia from the British, and Illinois became a county of Virginia in the new nation. The bell at Immaculate Conception, deemed the Liberty Bell of the West, rang in celebration.

“[This] was kind of a turbulent period because Virginia and the nascent United States were really not much better equipped to govern than the British had been,” says Meacham. “But then the Northwest Territory [was created] and because Kaskaskia was the largest and most economically significant community in the new territory, it became an important location. . . . That’s when Anglo Americans migrated there.”

Kaskaskia became the seat of St. Clair County in 1790, then the Randolph County seat five years later. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, brother of George Rogers Clark, visited Kaskaskia in 1803 to recruit participants for the Corps of Discovery. The Marquis de Lafayette made a stop in Kaskaskia during his farewell tour of America in 1825. With the influx of Anglo Americans, commerce boomed. The population was, at its peak, estimated between 3,000 and 8,000.

It was the natural choice to become the capital when Illinois was granted statehood in 1818.

Yet this period was not good for the Kaskaskia tribe. Through a series of treaties with the new nation, the tribe ceded all their land in Illinois except for 350 acres in Indian Kaskaskia and moved across the Mississippi.

Just two years after becoming the capital, Kaskaskia was passed over for Vandalia. In 1837, it was decided the capital would move yet again, this time to Springfield.

Kaskaskia remained an important commercial hub because of the steamboat trade. That all changed in 1844, when a terrible flood destroyed many buildings.

In 1868, the Illinois State Journal published an anonymous letter announcing the availability of land within the Kaskaskia commons for lease. The preface describes Kaskaskia as “the ancient seat of empire of all this western country, . . . a place around which cluster so many interesting historic events; the place that is particularly and peculiarly interesting to the memory of every old living inhabitant throughout the whole length and breadth of the Mississippi Valley.”

Kaskaskia did not recover. After more floods, the townspeople painstakingly dismantled Immaculate Conception church and rebuilt it in their new location, now Kaskaskia Island, along with the old courthouse. The bell is also housed there.

As residents continued to move away, ferry service stopped. The last school closed in 1987.

The Journal’s anonymous letter concluded, “From a population of more than eight thousand inhabitants, among whom, at one time, ranked the wealth and intelligence of the whole Northwest Territory, the old place has dwindled away to a mere shadow of its former self. . . . Whatever may be the fate which destiny has fixed for old Kaskaskia—whether it shall rise again to eclipse its former greatness, or whether it shall pass into ruins like Troy and Babylon—it will ever claim an important place in the annals of this country. The past, at least, is secure.”