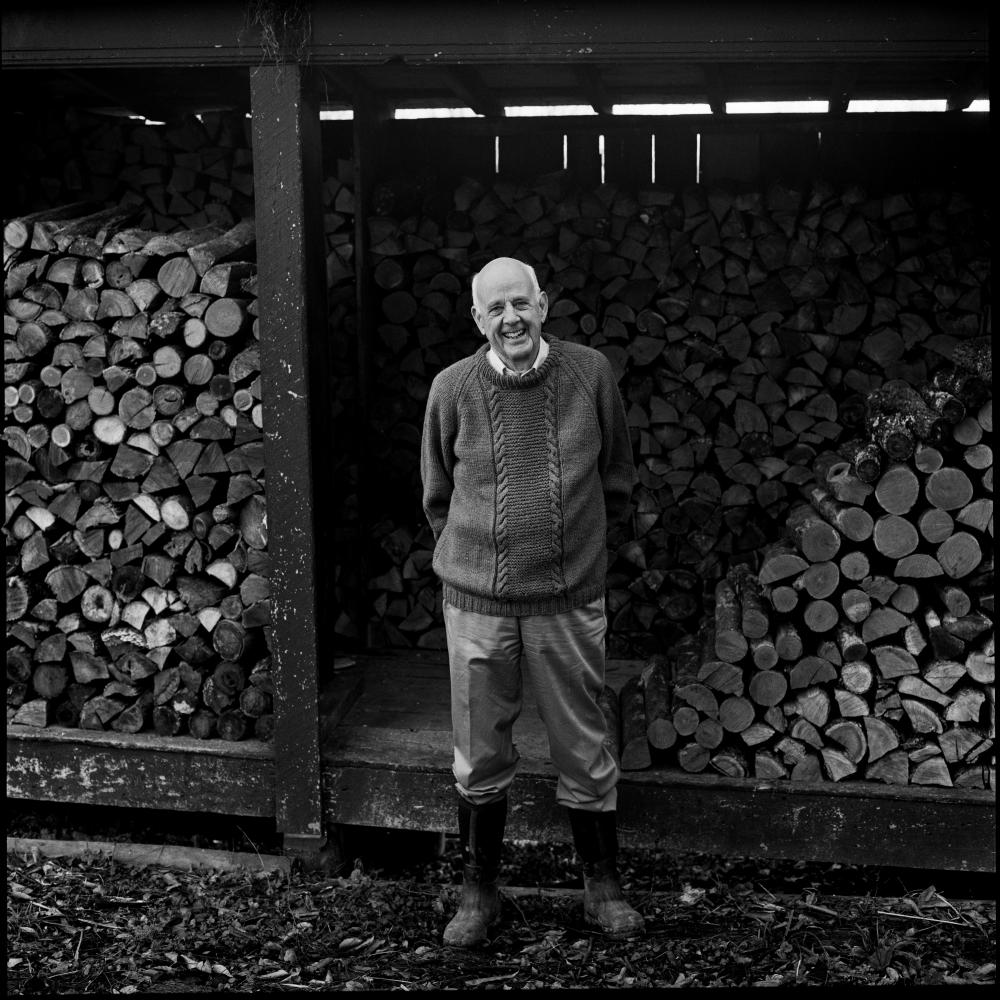

In 1964, a young writer named Wendell Berry left the cultural capital of New York, where he had been poised to climb the literary ladder, and returned to the rural Kentucky of his birth.

He taught college, continued writing, and began restoring the old farm he and his family still call home. At first glance, the arc of Berry’s life seems a clear case of trading the complexities of a career in Gotham for the simple serenity of life in the country.

But a prevailing theme of Berry’s work, expressed in dozens of stories, essays and poems, is that farming is an intensely demanding form of complexity in itself. He argues that in regarding—or disregarding—agriculture as a casually simple act, a chore so easy that any bumpkin or big machine can do it, we’ve ruined land, hollowed out communities, and debased our minds and spirits.

The remedy, he suggests, is a connection with land that is more than merely exploitive. His philosophy is best expressed in his most-quoted agrarian assertion, “What I stand for is what I stand on.”

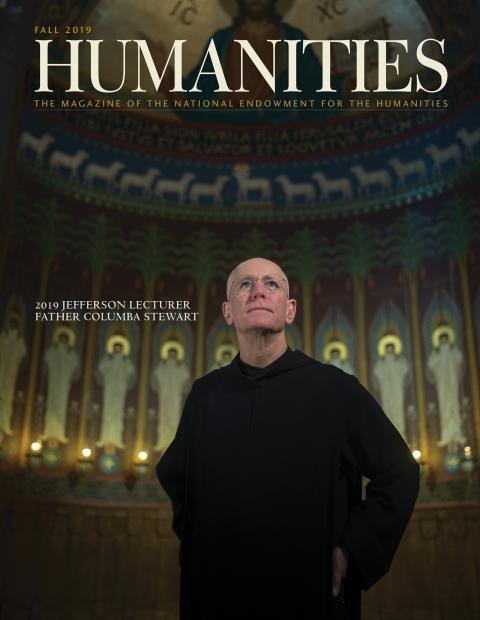

It’s the inspiration for the title of What I Stand On, a beautiful, two-volume collection of Berry’s essays published by the nonprofit Library of America. LOA, which focuses on definitive editions of classic American literature, published its first volumes in 1982 after getting off the ground with NEH support.

Berry has other connections to NEH. He received a National Humanities Medal in 2010, and in 2012 he delivered the Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, “It All Turns on Affection.”

“I will say, from my own belief and experience, that imagination thrives on contact, on tangible connection. For humans to have a responsible relationship to the world, they must imagine their places in it,” he told listeners back then. “To have a place, to live and belong in a place, to live from a place without destroying it, we must imagine it. By imagination we see it illuminated by its own unique character and by our love for it. By imagination we recognize with sympathy the fellow members, human and nonhuman, with whom we share our place. By that local experience we see the need to grant a sort of preemptive sympathy to all the fellow members, the neighbors, with whom we share the world. As imagination enables sympathy, sympathy enables affection. And it is in affection that we find the possibility of a neighborly, kind, and conserving economy.”

Berry’s lecture, included in What I Stand On, suggests the voice he uses throughout his essays, one deeply informed by growing things. “I am not suggesting, of course, that everybody ought to be a farmer or a forester,” he writes in his essay “In Distrust of Movements.” “Heaven forbid! I am suggesting that most people now are living on the far side of a broken connection, and that this is potentially catastrophic. Most people are now fed, clothed, and sheltered from sources, in nature and in the work of other people, toward which they feel no gratitude and exercise no responsibility.”

Every now and then in Berry’s essays, one discerns an echo of Ralph Waldo Emerson, his sentences summoning the reader to reflect with renewed clarity on how nature animates our ideals. “Love is never abstract,” Berry declares in his essay, “Word and Flesh.” “It does not adhere to the universe or the planet or the nation or the institution or the profession, but to the singular sparrows of the street, the lilies of the field, ‘the least of these my brethren.’ Love is not, by its own desire, heroic. It is heroic only when compelled to be. It exists by its willingness to be anonymous, humble, and unrewarded.”

Many have noted that Berry defies easy classification, but maybe one way of grasping his achievement is to view it within the tradition of George Orwell. Like Orwell, he’s concerned with the subtle corruptions of language, which bring about political and spiritual corruption, too. Berry critiques food labeling that distorts words into an alternate reality, from “In Distrust of Movements”: “When ‘homemade’ ceases to mean neither more nor less than ‘made at home,’” he laments, “then it means anything, which is to say that it means nothing.”

He also echoes Orwell in reserving a special ire for academic jargon, most notably in his essay, “The Loss of the University.” “That the common tongue should become the exclusive specialty of a department in a university is therefore a tragedy,” he tells readers, “and not just for the university and its worldly place; it is a tragedy for the common tongue.”

Berry’s essays, like Orwell’s, are the declarations of a moralist—quietly insistent and spare, their economy of expression an exercise in urgency.

That urgency, his readers come to learn, involves the fragility of the earth—and the reforms required to save it. “We seem to have forgotten that there might be, or that there ever were, mutually sustaining relationships between resident humans and their home places in the world of Nature,” Berry writes near the close of this collection. “We seem to have no idea that the absence of such relationships, almost everywhere in our country and the world, might be the cause of our trouble.”

What I Stand On is Berry’s alarm bell—clear, compelling, sounding with a clarity impossible to ignore.