How does a veteran make sense of the time they spent in uniform? How do they come to terms with all that they sacrificed and the experiences they carry with them into civilian life? These are old questions, but timely, too, urgent even, in places like Watertown, New York, due to the proximity of Fort Drum, home of the 10th Mountain Division, a light infantry unit that has served in Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, and Bosnia.

At Jefferson Community College in Watertown, veterans, active duty personnel, and their family members account for more than 40 percent of the enrollment, says Ronald Palmer, history professor and director of an NEH-supported project to help veterans gain a deeper understanding of their combat experience through the study of the humanities.

“This program was a natural fit for the college because of Fort Drum,” Palmer says. “We believed we could offer something special that would have the potential to make a difference in the lives of these veterans.”

Named “Dialogues of Honor and Sacrifice: Soldiers’ Experiences in the Civil War and the Vietnam War,” the program was designed for 15 students, veterans only. The majority of them had been deployed in combat zones. For many of them, this program was the first time they engaged seriously with the humanities.

Under a team of professors representing history, literature, film, art, and music, students explored the themes of honor and sacrifice. And they reflected on their own service in conflicts such as Afghanistan and Iraq as well as the challenges they faced when returning home from war.

“Although each person’s military experience is unique, there are commonalities in the experience of war,” Palmer says. “The idea is to have students remove themselves from their immediate conflict, and put their experiences in the context of other wars.”

Writing is an important element in the course. In journals, students reflect on what they get out of each class and discuss their personal experiences. All students have the option to make a note of anything they believe is too personal, and the professors won’t read those entries.

In the early fall of 2018, students were reading and discussing a variety of historical accounts and personal memoirs as well as letters and poems written by soldiers who fought in the Civil War and the Vietnam War.

Forty-three-year-old Eric Chargois served in the U.S. Army for 20 years before retiring as a sergeant in 2015 in El Paso, Texas. At first he was skeptical about the assigned class material and that any of it would relate to his own experience.

In the service, Chargois worked as a chemical operations specialist and was deployed four times, including three times to Iraq, where he recalls a particularly grim scene: multiple dead bodies situated so close to the road that they were lying in the path of the American Humvee Chargois was traveling in.

“Everyone is affected differently by that type of experience,” Chargois said. He had grown up in a tough neighborhood in Houston, Texas, and had seen people “who had died on the streets.” They were victims of an escalating crack epidemic, both users and dealers, and while he did not know any of them personally, the victims were sometimes family members or friends of his classmates. But in Iraq he experienced what he described as a complete disconnect.

Along with the other student veterans, Chargois was reading The Civil War and Reconstruction: A Documentary Collection, edited by William E. Gienapp. Some of the writings give detailed descriptions of the brutal conditions soldiers on both sides of the conflict faced on the battlefields.

One story, “An Iowa Soldier ‘Sees the Elephant’ at Shiloh,” is a harsh account by Cyrus F. Boyd, a 24-year-old Iowa farmhand who enlisted in the 15th Iowa Volunteer Infantry and, ten days after being issued a rifle, found himself at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee. His regiment was thrown into one of the bloodiest engagements of the war.

“Farther on the dead and wounded became more numerous,” Boyd recalled about the second day of fighting. “I saw five dead Confederates all killed by one six pound solid shot—no doubt from one of our cannon. They had been behind a log and all in a row. The ball had raked them as they crouched behind the log. . . . One of them had his head taken off. One had been struck at the right shoulder and his chest lay open. One had been cut in two at the bowels, and nothing held the carcass together but the spine.”

That story and others “brought me back to Iraq,” said Chargois, “to all those dead bodies already on the ground after a bombing.”

The reading helped him realize that soldiers throughout history have experienced the same detachment he experienced. Studying the Civil War also helped him appreciate those who were fighting to abolish slavery, said Chargois, who is African American. He had been unaware of letters written by members of the 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, who, like the more famous 54th Regiment, had endured discrimination while serving in the Union Army. Both regiments were made up of African Americans, who were paid less than white soldiers.

Their protests often came in the form of letters, sometimes written by family members. One of those letters read by the students was written to Massachusetts Governor John Andrew by Rachel Ann Wicker, whose husband and son were both serving in the 55th Regiment. In the letter, which is included in the collection edited by Gienapp, Wicker described financial hardships being suffered by the African-American soldiers’ families.

The African-American soldiers serving in both regiments eventually received the same wages as the white soldiers. “That was both surprising and inspirational,” Chargois said.

Although Chargois is retired from the military, his wife is still serving and stationed at Fort Drum. When she retires, they plan to return to Texas, where he hopes to start his own food truck business (he has already earned a hospitality and tourism degree from Jefferson, along with an individual studies degree).

The Dialogues course, Chargois said, has been one of the most meaningful courses that he has taken at the college. “Many of us in the class have found something that reminded us of our time served. Everything we tap into hits home.”

Another assigned reading, The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien, described soldiers’ experiences in the Vietnam War through items they carried, from flak jackets to Bibles and personal diaries. The book reminded Chargois of his first deployment, when he decided to wear a cross necklace that his mother had given him.

“I’m not a very religious person, but I decided to wear that cross during my first deployment to Kuwait,” he said. “I came home safe, so I decided after that day, I would wear the cross during every deployment afterwards.”

For Stephanie Eriacho, who is forty-two years old and originally from New Mexico, sharing stories with other veterans has been an invaluable part of the course. It’s helped her feel less alone. She retired in 2012 from the Naval Air Station in Whidbey Island, Washington, as a petty officer first class.

In the U.S. Navy, wherever she went, respect and discipline were the rule. But, she said, “when you get out of the military, it’s quite a culture shock. You’re suddenly in the civilian world, and you have to adapt quickly. At first, I thought I was the only one who felt like this.”

Through journaling exercises and classroom discussions, however, she has learned that others sometimes felt lost, too. And she has learned to move forward, she said, thanks to the support of her husband and her own desire to be the best mother she can to her children. At Jefferson, Eriacho is pursuing a dual major in physical education and homeland security.

The assigned readings, too, have made a big impression. “Those letters by the Civil War soldiers writing back home to their families, those were hard for me to swallow at first, because they hit so close to home,” she said.

Eriacho joined the Navy at her father’s insistence when she was twenty years old. Her father believed the military would give her the opportunity to see the world outside of the federally recognized Zuni tribe reservation, in western New Mexico, where she was raised.

Many other Native Americans from her reservation also joined the military, seeking both job and travel opportunities. She was hesitant at first, but joining the military turned out to be, said Eriacho, “the best decision I ever made.”

Eriacho has been deployed to Iraq, where she worked as an aircraft mechanic on equipment used for reconnaissance operations. She can still recall hearing the mortar attacks at night. And she traveled while serving missions in Afghanistan, El Salvador, Japan, Bulgaria, and Germany.

“When we read parts of the journals written by the Civil War soldiers,” Eriacho said, “I realized the majority of them felt like us when we had been serving in Afghanistan.”

Reading about the Vietnam War for her Dialogues class, Eriacho thought about her uncle, who had served in Vietnam. “When he came back from Vietnam,” she said, “he was so proud of wearing his Army uniform, but after walking into the airport, so many people spit on him and called him a baby killer, that he ran into the bathroom and changed into civilian clothes.”

“It’s different now,” she observed. “Military personnel walk through the airport, and people clap for them.”

Eriacho has recently reached out to her uncle and started to interview him about his experience in Vietnam. She hopes one day the interview will become part of the historical record.

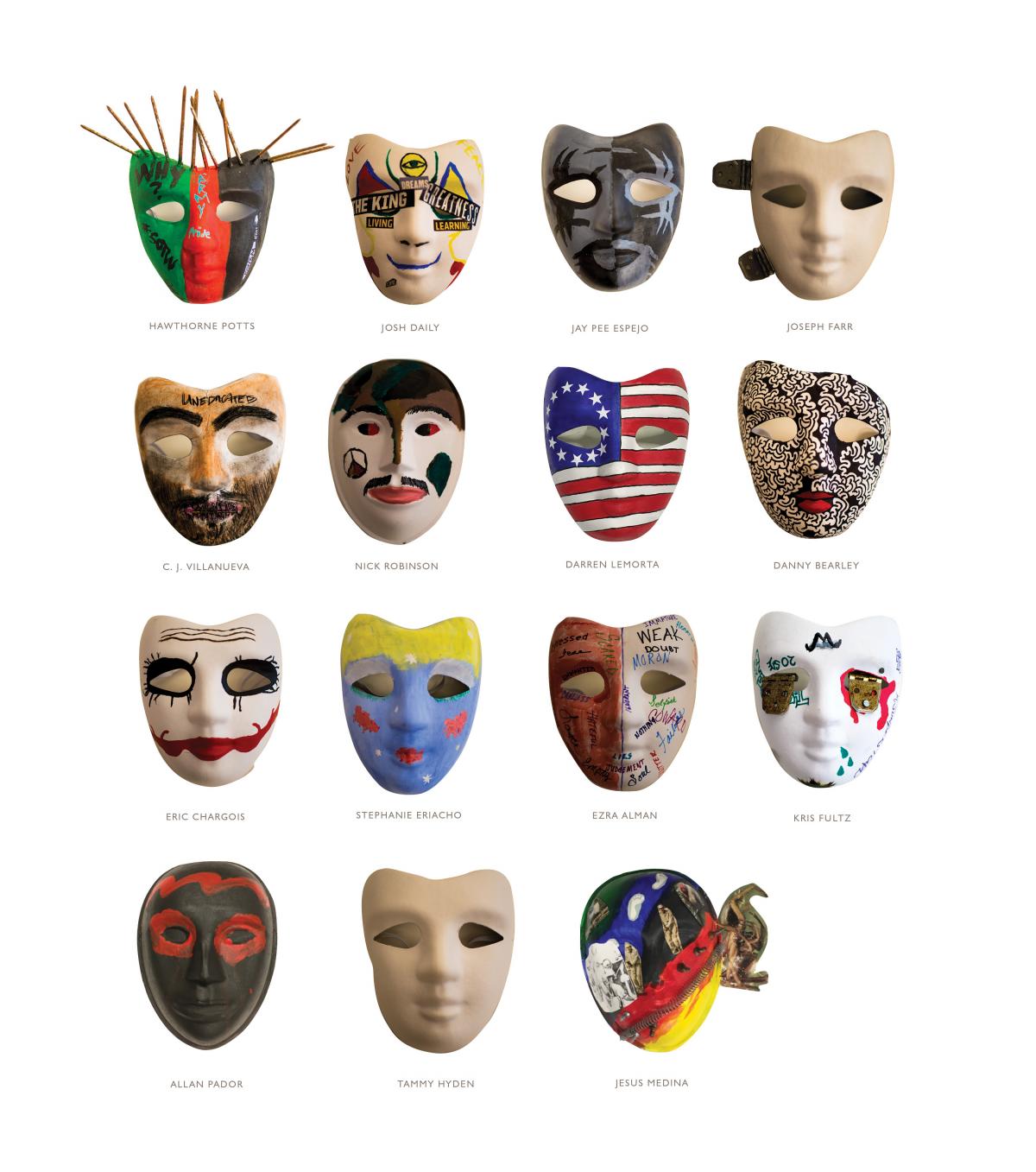

Inside a large studio, art professor Lucinda Barbour introduced the student veterans to art therapist Kim Kernehan, who was there to help them create inside-outside masks.

“The outside of the mask represents what we pretend to be, what we appear to be, or how we feel others are perceiving us,” Kernehan said. “The inside represents who we really are, what we are truly feeling, and how we perceive ourselves.”

The teachers distributed a variety of art supplies to use to decorate the plain white face masks. There were also small boxes with an assortment of nuts, bolts, and screws that had been donated by a local hardware store.

As the paint dried on his mask, veteran Darren LeMorta paused to consider his next steps. The outside was meticulously painted to resemble an American flag, reflecting, he said, the face of a patriotic soldier. The inside was going to be painted black, and, when that dried, LeMorta was planning to paint the names of his friends who lost their lives fighting with him in Iraq.

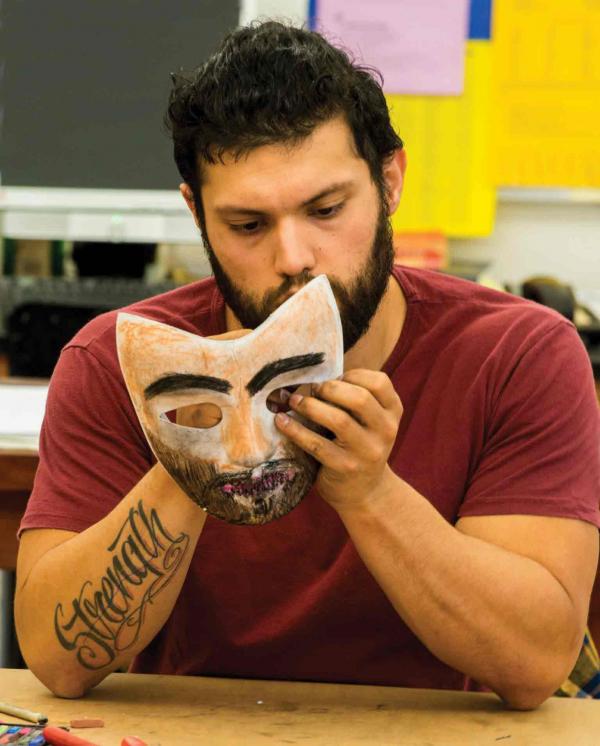

LeMorta, who served four deployments in Iraq, has spent a lot of time talking about his combat experience in therapy sessions. But, inside this college classroom, he appreciated the opportunity to convey his feelings using color and imagery. “I find this approach helpful,” said the veteran, who attends every class with his service dog, Gemma, who lies quietly by his feet. “It gives me a way to express myself without having to talk.”

Christopher James “C. J.” Villanueva, sitting at another table across the room, painted a harsh-looking face on the outside of his mask, using nails for teeth and writing the word “uneducated” across the forehead. “That’s how people perceived me, but that doesn’t represent who I am,” he said. Villanueva, who is Hispanic and a native of Texas, worked as a farm laborer before entering the military.

“There’s a certain level of racism that’s accepted in this country, but it’s hidden,” he said. His ethnic background, combined with his work history, he said, led others to believe he was not smart. But after serving in the military for several years, and starting college at Jefferson, Villanueva has found a way to formally educate himself about topics that have always interested him, such as history and politics.

On the inside of his mask, he paints the words “economics of war, health care, and campaign finance reform.” He said, “Those represent the real me: I’m concerned about all those issues. And I continue to educate myself about them.”

Tammy Hyden, a native of Idaho, started painting the inside of her mask with a myriad of black lines, then filling the spaces between with splotches of color, small dots, and curvy lines. “It represents the turmoil that I feel,” she said. She was not quite sure how she was going to paint the outside of her mask.

Hyden worked as an emergency medical technician and a 911 dispatcher before joining the military at age thirty-nine. Working as an army medic in Afghanistan, she said, she “saw more than anyone should have to see in their lifetime.”

She left the military after ten years of service due to an injury, and decided to enroll in college. She took this course to fulfill an elective for her nursing degree. “I’m not a history person,” she said. “I was hesitant about taking this class. But it’s changed my mind completely about how we can relate our own experiences to past history.”

Hyden admits prior to starting the course, “I had no desire to learn more about the Vietnam War or the Civil War, but the way the material has been presented has really broadened my mind to learning more about history.”

“So much of what we read and discuss about these wars sounds familiar to what we have experienced in places like Afghanistan,” she said. “It’s like, ‘Oh, those soldiers felt that way, too.’”

In a recent literature class, students listened as the veteran and poet Paul David Adkins read a poem of his entitled “Fruit Stand.” In it, a Humvee carrying American soldiers hits a small IED while driving through a village.

“It must have seemed funny to the Iraqis. / A convoy hit an IED, a small one— / no one hurt, no damage,” Adkins read. “The commander, who literally pissed himself, / hopped out and tottered / to the stand with his terp to ask / who knew anything about it. / Out of breath, stuttering, a frightened Elmer Fudd.”

Adkins continued, “It must have seemed funny / because the fruit stand owner laughed / at him as he spoke. The customers / laughed. Women and children / laughed.” Upset and outraged, the commander walked back to his Humvee, grabbed a baseball bat, and returned to the fruit stand. In seconds, his bat comes crashing down on the tables, destroying melons, oranges, and soda cans.

“Now laughter perked up from the Humvees, the guards, the commander screaming, / Who’s laughing now, as his pulp-dripping bat rose and fell.”

The poem appears in Adkins’s most recent book, Dispatches From the FOB: A Poetry Anthology, a collection of new poems and previous works. Adkins served in the U.S. Army for more than 21 years, retiring as a sergeant first class. He toured Afghanistan once and Iraq three times with the 10th Mountain Division.

“Fruit Stand” was based on a story Adkins heard while serving in Iraq, although the details were not reported through “official channels,” he said.

“What made it authentic to me was how it seemed to capture the frustration of fighting guerrillas (Iraqi fighters hiding among civilians) as a traditional force (a group of American soldiers),” Adkins explained.

After Adkins finished reading his poem, several students expressed frustration at how the American commander was portrayed.

“A strong leader would not piss himself,” said one student bluntly. Furthermore, said the student, a good commander would have never gone after the group of Iraqi civilians, because it could have endangered the soldiers under his command. “When you’re in uniform, you’re supposed to be a professional.”

Another student across the room said, “When we drove a convoy of trucks in Afghanistan and kids threw rocks at us, we didn’t go after them. We knew there were mixed emotions and feelings toward Americans in that country—some wanted us there, and others wanted us to get out.”

But a student sitting at a different table said he viewed the commander portrayed in the poem as having an understandable reaction. “Things happen over there, and people can overreact,” he said. “Everyone is under a lot of stress.”

One student did not find the laughter of the Iraqi citizens to be very surprising. “The people at the fruit stand may have been laughing because . . . they live in a country affected by violence on a regular basis,” he said. “So, they probably viewed the commander as being ridiculous.”

Still another student questioned the use of the word laughter in a poem that did not appear to be at all funny. Actually, the laughter in the poem was not meant to imply anything humorous, Adkins explained: “It represented an interplay of power between two disparate groups.”

Poetry, he continued, should “allow the reader to exist within the framework of the poem” and leave room for the reader to forge their own interpretation.

A poem might be inspired by a real event, Adkins said, but that was no reason for it to be restricted by a real event. As poets, the students should feel free to “operate in a framework of general experience, not specific” because, he said, “poetry creates its own truth.”

After the guest speaker left, a list of writing prompts was passed out to help students start on their poems. These included, “First year of training . . . ,” “When I try to sleep at night . . . ,” and “My pack, my gear, my weapons . . . .”

The exercise was a start, a way to brainstorm a few sentences to see if the direction of words made sense. Some chose words to speak of pride in their service, others chose words that resonated anger or frustration.

Near the end of the class, a student shared a poem he had written from the perspective of a civilian, returning to his home after a bombing, and finding his house in a pile of rubble and his two-year-old son dead. The student choked up as he searched for the right words to describe the father’s pain.

“It’s okay, man, take a drink of water, just take a drink of water,” said a fellow student, seated at the next table. That was all that needed to be said. The room fell silent, and class ended a few minutes later.

The course’s themes of honor and sacrifice were explored yet again as students watched clips from the 1989 film Glory, which tells the story of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, the first African-American unit to organize to fight in the Civil War.

The regiment was led by a white commander, Colonel Robert Shaw, whose many letters home detailed the challenges faced by his men. In addition to reading Shaw’s letters, students prepared for class by reading Writing About Movies, in which they learned about such cinematic concepts as mise-en-scène, a French term for the staging and “the complete look and feel of a movie.”

The final battle scene was played in class. It showed soldiers of the 54th Regiment charging up the hill and trying to overtake the Confederate soldiers holding down Fort Wagner in South Carolina. The 54th Regiment soldiers were depicted as courageous and full of tenacity, even after their commander, Colonel Shaw, was shot and killed near the start of the battle.

Christine Grimes Topping, associate professor of English, pointed out the location of the actors in the scene just prior to the battle: The Confederate soldiers were stationed inside Fort Wagner on the top of a hill, and the union soldiers were hiding together in trenches at the bottom.

“The shot seems to convey power, that the people down below have less, and the people above have more,” she said.

Margot Jacoby, adjunct instructor for English and Speech/Theater Arts, encouraged the students to pay attention to how music was used in the film, asking, “Does it complement the images being presented?” Several students agreed the music definitely set the tone of the scenes, particularly the final one, with strong, intense, and fast-paced music playing as the soldiers charged up the hill. “That indicated it was going to be a tough battle, and people were running to their deaths,” said one student.

The music becomes slow and somber in the next scene, the following morning, as ocean waves wash ashore next to the dead bodies of Shaw and many members of the 54th Regiment, who were later buried together in a mass grave near the beach.

“Many people have called the film a tragedy,” said Topping.

But, in another way, it was actually a triumph, said one student. “Those members of the 54th Regiment wanted an opportunity to fight. They didn’t care if they died,” he said. “They were trying to prove they were ready and willing to die for their country. Those soldiers were fighting for an end to slavery.”

The students also discussed the camera angles and the focus on particular actors, such as when Shaw, played by Matthew Broderick, makes the decision to charge Fort Wagner with the regiment, and the reaction of Sgt. Maj. John Rawlins, played by Morgan Freeman, when he realizes their white commander is willing to die with them.

“It was a powerful moment,” said another student. “Those close-up shots reflected the mutual respect they had for each other,” a critical requirement for soldiers in combat, he said.

Nobody disagreed on that point.