In the captivating survey, “Comparative Hell: Arts of Asian Underworlds,” the damned are boiled alive. Writhing in pain, they are skewered, mauled by dogs, and devoured by ink-black birds. But the show is dotted throughout by charming reprieves: a lush jade-green garden, creamy-white blossoms, and whirling clouds. This is a hell that delights as much as it punishes.

Curated by Adriana Proser of the Walters Art Museum, “Comparative Hell,” which travels this summer from the Asia Society Museum in New York City to the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, spans 12 centuries and four religious traditions—Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Islam—each conjuring up a hell alternately harrowing and beautiful.

“Hell continues to be a subject that horrifies yet fascinates,” writes Proser in the exhibition catalog. “We cannot turn away from these telling images.”

It’s nearly impossible to turn away from The Kingdom of Yama, a grand Nepalese work on cloth, from 1900. Yama, the king of hell in the Hindu tradition, sits in a domed pavilion. A naked man, eyes downcast, stands before him, awaiting the king’s judgment. The work, presented under glass at the Asia Society Museum, is maze-like, the eye traveling from Yama’s court to the fire-red demons at the gate to the cauldron across the way, where skeletal bodies bob in twilight-blue water. Situated under an eerily crimson sky dipping under jagged, pitch-black mountains, here is the worst kind of hell. Or is it? In the foreground, eggshell-white flowers bloom, ducks sit in a still pond, and a deer rests in a verdant forest. There is a kind of levity, for a moment. The effect is confounding: Nothing here is as it should be.

The same holds true in Day of Judgment, a 1555 folio from Tabriz, Iran. Lining the work’s upper edge is a garden of periwinkle, orange-red, and white florets; in the middle ground, a veiled Prophet Muhammad and Imam Ali, adorned in lapis-blues and coral-reds, intercede on behalf of their followers. The foreground, though, is lifeless: There the condemned, some a ghostly gray, others with swine-like heads, plead for mercy. They are devoid of color, their very souls seeping out of them. Here the radiant and repulsive are side by side and worlds apart.

“You are seeing something beautiful in the background as a kind of promise, if you behave yourself,” Proser explains. As torturous as the punishment might be, salvation exists, too, just out of reach.

The promise is elusive in Hell Courtesan, an Edo-period ink on silk. Set against a moss-green ground, the fifteenth-century courtesan stuns in a rich, billowing robe. As the legend goes, the pale-faced, raven-haired woman was kidnapped and sold to a brothel, where she became the disciple of a Buddhist monk.

“She’s an almost feminist icon,” says Laura Weinstein, a curator at the Asia Society Museum. “Even as a courtesan she could achieve enlightenment. And she did."

In “Comparative Hell,” the courtesan’s voluminous robe has the air of a storybook, with chilling scenes rippling across its cascading folds. One depicts a sinner held by the hair and forced to watch his misdeeds in a mirror. On the courtesan’s back, a disembodied eye and nose float above the turmoil, ever watchful. And yet, woven throughout her garment are glimmers of light: a powder-blue trim, a gold-inflected flourish, a fire-red and canary-yellow cloud that coalesce into a tonal symphony.

The hell courtesan is magnetic, luring visitors like moths to light. To follow the lines of her kaleidoscopic robe is to question the very nature of hell and, its close companion here, beauty. The work brings to mind a hell on earth: the bombing of Hiroshima, in 1945. Yoshitaka Kawamoto, a survivor of the blast, was thirteen when the atomic bomb detonated less than a mile away from his school. Frozen with fear at the sight of bodies floating in the muddy water, Kawamoto looked up: “I saw the cloud, the mushroom cloud growing in the sky. . . . It caught the light and it showed every color of the rainbow. . . . It was beautiful.”

What’s most unsettling about “Comparative Hell” is not its ghosts and fiery tombs but its dappled light. Like the glow of a cloud in the aftermath of a bomb, it lulls as it transfixes, leaving us under its spell.

Equally spellbound are the eyes in the exhibition. Whether of demons or sinners, snakes or dogs, the eyes in “Comparative Hell” betray a central conceit: Something here is not right.

Flanking Hell Courtesan in the show is a small work, bursting with blood reds and forest greens. In Newly Published Comic Picture of Cats, a late nineteenth-century Buddhist print from Japan, cats torture mice in a smoldering hell. The work, intended to teach children how to behave, disturbs, not least because of the cats’ menacing smiles and yellow, maniacal, eyes. If this is a child’s world, it has gone awry, coursing with rivulets of fire.

Frightening gazes disturb, too, in Bima Swarga, a 1970 work on cloth from Indonesia. Teeming with chartreuse and cadmium-green trees, the Hindu-inspired picture seethes with energy as demons, with eyes wide and ringed with red pigment—blood, perhaps—terrorize many of the damned, while others are clobbered by straw-yellow birds or devoured by caterpillars. The demons here sprout up like spores on rotten fruit: What life remains is wasting away.

A similar air runs through an Edo-period triptych in the next room. One work in the series, Datsueba, the Old Woman Who Snatches Away Clothes, is especially foreboding. Known in the Buddhist tradition as the Hag of Hell, who strips sinners of their clothing, and sometimes skin, Datsueba sits crouched here, smiling menacingly at the sinners below. Her face and body are lined, like the garment falling off her shoulder. Her eye is a single black dot in a dirt-brown socket. Her stare, like a crocodile’s as he awaits his prey, is still, poised to strike. Perhaps hell is, as Jean-Paul Sartre wrote in No Exit, the judgement of other people. Or maybe it’s just their gaze.

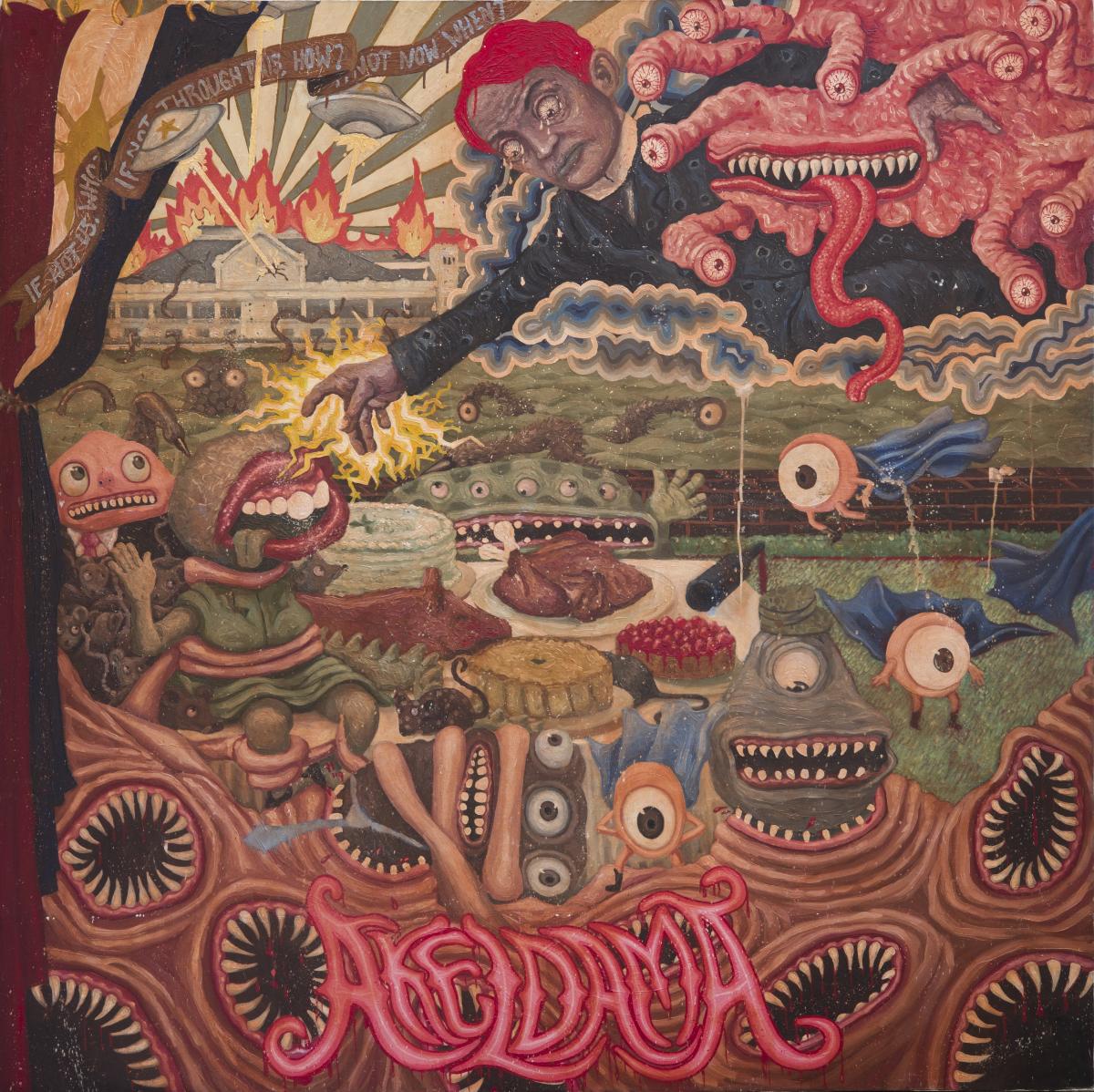

The show closes with Luis Lorenzana’s Akeldama, a 2006 painting from the Philippines. The title, Aramaic for “field of blood,” is a reference to the passage in the Acts of the Apostles when Judas, having betrayed Jesus, buys a field with his reward, only to fall to his death, his intestines bursting. In the painting, forms ooze every which way. Eyes without faces and organs without bodies saturate the salmon-pink picture, pooling in the foreground. A candy-red-haired man, identified in the catalog as Filipino national hero José Rizal, juts across the frame, his accusatory hand shooting lightning bolts into the ground below. Rizal here appears tormented, eyes bloodshot and gaze weary. A commentary on the mistreatment of the Filipino people at the hands of the state’s elite, Lorenzana’s work is piercing and, like a sleepless eye, wide awake.

The twelfth-century Japanese poet Saigyo encountered similarly evocative paintings of hell on one of his pilgrimages. While the pictures were destroyed and his exact travels unknown, his poems are a testament to the power of images like these—works intoxicating and haunting—to awaken in the viewer a kind of sympathy.

“Just looking fills me with woe,” Saigyo writes. “What am I to do / with this heart of mine? / For I too have sins / that merit this kind of recompense.” Saigyo sees himself in hell’s tortured and forgotten victims: For a moment, they are one. The feeling carries over to the show, where swarms of visitors are clustered around this occasionally blissful but more often shudder-inducing work. How did the condemned get here, the mind begins to wonder when faced with one of these pictures. And how, if ever, will they escape?

“Images of hell are most powerful,” Proser writes in the catalog, “when they are informed by the greatest human fears.”

Those fears—of being tortured, of something happening to a loved one—are universal, Proser insists. They “lurk within us all.”

In one of the final rooms in the show hangs Jizo, the Bodhisattva of the Earth Matrix. Jizo, known in Japan as the protector of children and travelers, can intercede for the condemned. In “Comparative Hell,” Jizo is lithe, suspended in a diaphanous cloud, an azure-blue shawl and rose-red banner punctuating the otherwise diffuse, dream-like picture.

Saigyo closes his poem with a nod to Jizo and the promise to come. “In the morning sun, / their suffering, like frozen ice, / will melt away— / The sound of his six ringed staff / echoing through the dawning sky.”

The famous warning to "abandon all hope, you who enter," which hangs over the Gate of Hell in Dante's Divine Comedy, seems premature in a show like this one. Perhaps the better approach is to enter boldly, or, at the very least, to have a look around.