Places, real and imaginary, were important to Ursula Le Guin.

Her first Earthsea fantasy novel began with a map of islands that she drew for herself in a paper-and-ink archipelago, which offered her the freedom to imagine who might live there. Real places inspired not only her realistic but also her speculative fiction, where the situations were imaginary but the emotionally charged landscapes were often based on ones she knew and loved. In the new documentary Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin, she tells director Arwen Curry, “I don’t feel so much as if I were ‘making it up’; I know I am, but that’s not what it feels like. It feels like being there and looking around, and listening.”

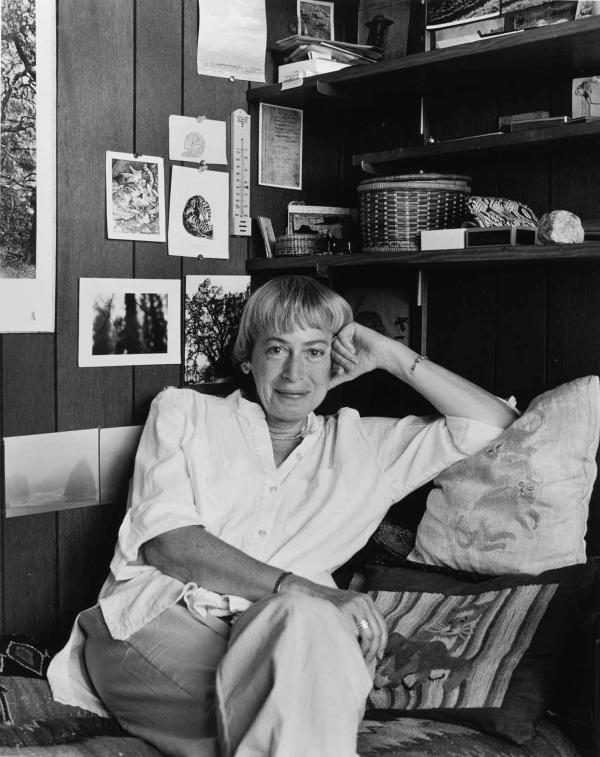

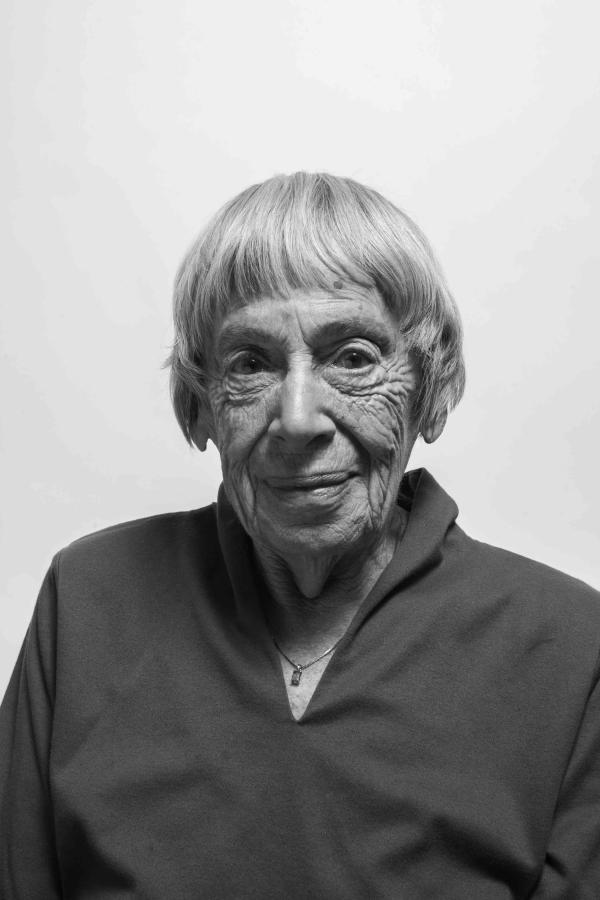

The American West forms a stunning backdrop to Curry’s look at Le Guin’s life and work. Curry filmed interviews over a period of several years with the essayist, poet, and novelist, who died at age 88 in January last year. We see Le Guin at her home in Portland, Oregon (and during a reading at Powell’s, her hometown bookstore); in the otherworldly high desert of eastern Oregon; and at the rocky Oregon coast, all settings that inspired Le Guin’s writing. At the same time, Curry tracks the progress of Le Guin’s career from the margins of literature to the center.

Born in Berkeley, California, in 1929, Le Guin began publishing science fiction in the early 1960s and within ten years was acknowledged as one of the most important writers in the genre, particularly with the publication of A Wizard of Earthsea (1968), The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), and The Dispossessed (1974). Curry makes it look like Le Guin rescued science fiction and fantasy more or less single-handedly from a state of literary neglect, which isn’t exactly true. (There were other writers who saw the genre’s potential for yielding enduring literature.) But Le Guin chose this “despised, marginal” genre, she once said, for a reason she couldn’t acknowledge to herself at the time: Because it was “excluded from critical, academic, canonical supervision, leaving the artist free.”

Le Guin remained loyal to her chosen field but sought artistic freedom by working in many different genres, including poetry, historical fiction, picture books, essays, translation, and, toward the end of her nearly sixty-year career, writing a funny and opinionated blog. In fact, she began her career with little interest in popular culture. She was a graduate student in Romance languages at Columbia University, researching a doctoral thesis on medieval French poetry, when she married historian Charles Le Guin in Paris. They were fellow Fulbright scholars who had met on the boat traveling to France. She used the marriage as an excuse to drop out of grad school and write full time, creating historical novels and short stories set in an imaginary country she called Orsinia. Years later, she observed that in much of American literature “imagined things are second-rate compared to real things. And then reality becomes constricted to urban life in the East. Everything else is called marginal or regional, or genre.” Yet she already sensed that realism was “small and stony ground” for her imagination.

When she found her way into science fiction and fantasy, those genres turned out to be well suited to her imagination, her curiosity, and her subversive suspicion that man was not the measure of all things. From the very beginning, in interviews and essays, Le Guin championed science fiction’s literary value. She did it most memorably in a 2014 speech when she accepted the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters (or what writer China Miéville in the documentary calls “the welcome-to-the-canon award”). In that speech, she described herself and her colleagues as “realists of a larger reality.” When she received the National Book Award for children’s literature in 1973, she said much the same, urging the audience not to underestimate the truth-telling potential of imaginative literature. Fantasy writers, she told them, can speak seriously “about human life as it is lived, and as it might be lived, and as it ought to be lived. . . . It is above all by the imagination that we achieve perception, and compassion, and hope.”

Curry also filmed Le Guin in California, at the Napa Valley farmhouse where she spent the summers of her childhood in the ’30s and ’40s, and where her family still gathers. Her father, Alfred Kroeber, was a leading expert on California Indian cultures and the founder of the anthropology department at the University of California, Berkeley. Her mother, Theodora Kroeber, was the granddaughter of pioneers and in later life became a writer in her own right. Le Guin grew up the youngest and the only girl of four formidably well-read and intellectually agile children. Her father, in particular, was a storyteller who liked to tell tales around the campfire on summer nights.

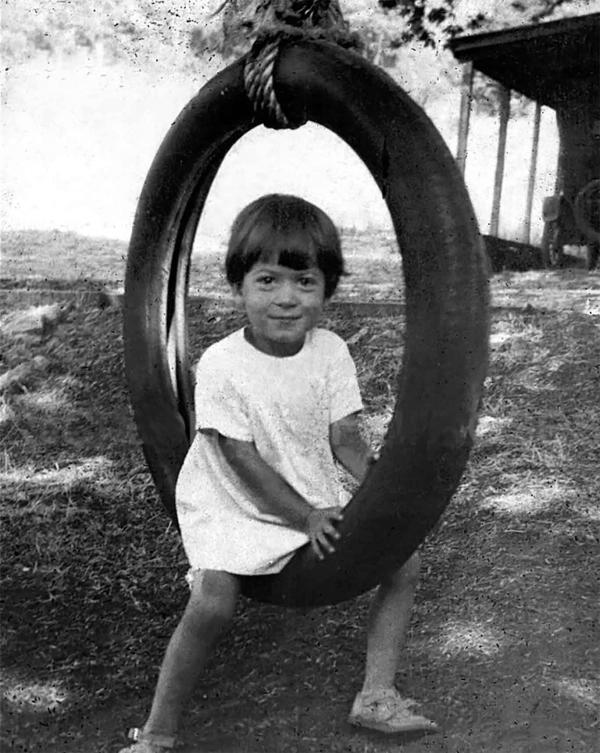

Archival photos show a small Ursula Kroeber playing games with her brothers, seated in the family’s Model-T Ford, or sitting on her own with a dreamy look. Spending summers at the Napa house, Le Guin tells Curry, was “heaven for an introvert.” But, as she slowly came to realize, her heaven had a sorrowful history. Before her birth in 1929, her father had spent much of his career “going around California, on foot, by horse, talking to survivors of destroyed peoples” who were trying to save what was left of their culture. One of them was the Yahi tribesman who came out of the Northern California forest in 1911 as the last survivor of his people. Alfred became close to the Yahi man, who became known as Ishi, and Theodora made his story famous in her 1961 book Ishi in Two Worlds.

Le Guin has said her fiction reflected attitudes she learned from her father: “curiosity about people different from one’s own kind; interest in artifacts; interest in languages; delight in the idiosyncrasies of various cultures; a sense that time is long yet that human history is very short—and therefore, a sense of kinship across seas and centuries; a love of strangeness; a love of exactness.” Some of her protagonists are anthropologists attempting to understand people very different from themselves, like Genly Ai in The Left Hand of Darkness, an envoy from a future Earth who must navigate unfamiliar social codes in a society in which people have no gender. In an interview, Le Guin observed that her central characters were often people “alone of their kind among people of another kind” and added, “this is Ishi’s situation; also the situation of a field anthropologist; also the situation (or so it seems to me) of most adolescents, most intellectuals, most artists.”

Traveling to an unfamiliar place often has ethical implications in Le Guin’s fiction, most notably in one of her best-known works, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” This brief parable begins by introducing an imaginary city. Then the narrator turns to you, the reader, and asks you to fill in all the details you might need to make the city of Omelas your personal utopia, a place of “boundless and generous contentment.” As the writer Neil Gaiman describes it, “You are part of this, you are creating this with her, and you experience, for several pages, this wonderful city of noble people, the city of cities, Omelas. And then she says, there’s one more thing.”

The catch is that readers are asked to picture a neglected, starved, wretched child. Then they learn that the beauty and joy of Omelas depends unconditionally on the misery of the one. “It sets out, and it says, this is a thought experiment,” Gaiman says. “And then it goes in and it breaks your heart.”

Though “Omelas” is in a sense barely fiction at all, it is characteristic of Le Guin’s work in at least one respect: It challenges the reader to think beyond the ending. Those residents of Omelas who cannot accept the condition of their happiness must walk away and never return. Where do they go? “Omelas” is often taught in high schools because of its power to provoke discussion around this question, and students are often frustrated with this problem with no solution. Le Guin tells Curry, “My job is not to arrive at a final answer and just deliver it. I see my job as holding doors open, or opening windows. But who comes in and out the doors, what you see out the window—how do I know?”

Her willingness to ask questions and her love of imaginative freedom have made her work influential among activists and community organizers. Activist and editor Walidah Imarisha recently observed that Le Guin’s writing taught her the value of the imagination in conceiving social change. “We need imaginative spaces like sci-fi if we are going to build new, just futures. We have to have space to dream the change we will build.”

Adrienne Maree Brown, who co-edited, with Imarisha, the anthology Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements, tells Curry that she constantly urges The Dispossessed on fellow activists. Le Guin’s novel exploring the potential—and the potential pitfalls—of a pacifist anarchist society based on mutual aid is, Brown says, “a foundational book. . . . It reminds us that the way we live right now is not the only possible way for humans to live.”

Le Guin herself asked radical questions about fiction, working in new genres, taking her writing in new directions. In particular, like most women who began writing before the second wave of feminism, she reached a point when she had to reevaluate what she was doing and whether or not it was true to her lived experience. In her early work she wrote mainly from male protagonists’ points of view, in part because that was very much the norm in her chosen genre. By the late 1970s, she had begun exploring female perspectives, at first with difficulty, later with more confidence. She tells Curry, “It was a radical revision from within of my whole enterprise in writing, and for a while I thought it was going to silence me. But I think if I hadn’t gone through with it and learned how to write from my own being as a woman, I probably would have stopped writing.”

She also resisted the approach to writing that emphasized that fiction must have a hero, a conflict, a storyline. Why should the shape of a story be a line? she asked. Why should it move in only one direction? She began publishing realistic short stories in the New Yorker and wrote the ambitious and unconventional work of fiction and poetry Always Coming Home, in which she returned to the Napa Valley, drawing on the landscape and on native Californian cultural traditions to imagine a sustainable far-future society. She later said it was, among other things, an “attempt to imagine . . . a world where the Hero and the Warrior are a stage adolescents go through on their way to becoming responsible human beings, where the parent-child relationship is not forever viewed through the child’s eyes but includes the reality of the mother’s experience.” Can a mother be the protagonist in heroic fantasy, she asked? Her 1990 novel, Tehanu, the last book of the Earthsea series, is her ambivalent answer, placing the middle-aged mother Tenar as the protagonist instead of the wizard Ged.

In recent years, Le Guin has also been recognized by a wider public as a lively and irreverent essayist and critic. Her collections Words Are My Matter (2016) and No Time to Spare (2017) draw on this late outpouring of nonfiction, which began after her last novel, Lavinia, was published in 2008. Witty, irascible, and accessible, they have brought yet another audience to her work. Starting in the 1980s—a time when she had gained literary recognition for her work and her three children had left home—she became an outspoken public intellectual. Despite her sense of herself as an introvert, she began giving readings and lectures and proved a charismatic speaker. Her daughter Elisabeth Le Guin recalls, “She really began to move into herself, to own herself as someone who has a voice and the authority that goes with that voice and the right to use it.”

When Ursula Le Guin died in January 2018, at 88, she was in some ways at the height of her fame, with her novels embraced, her essays celebrated, and her influence acknowledged by a younger generation. Right now, her willingness to imagine alternative futures seems more necessary than ever. In her 2017 essay collection, No Time to Spare, she argues that fantasy has a subversive streak, because it doesn’t take the current reality for granted. “Fantasy not only asks ‘What if things didn’t go on just as they do?’ but demonstrates what they might be like if they went otherwise,” she writes.

As for the charge of escapism, what does escape mean? Escape from real life, responsibility, order, duty, piety, is what the charge implies. But nobody, except the most criminally irresponsible or pitifully incompetent, escapes to jail. The direction of escape is toward freedom.

Freedom was Le Guin’s artistic and personal watchword. She searched for it in the realm of the imagination and invited her readers to travel toward freedom with her.