When Emil Her Many Horses (Oglala Lakota) was a junior in high school, he saw a beaded work he wanted but couldn’t afford. He resolved to learn the art himself, with the help of his grandmother and Alice Fish, a well-known artist on the Rosebud reservation, whom he’d prod with endless questions. As he put it, “I would basically go bother her all the time.”

It paid off. The first piece he made was a cradle board of beaded horses. He submitted it to an art show in Sioux Falls, where it won first prize. Since then, Her Many Horses’s work has shown across the country. Today, he is a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, where he organizes exhibitions such as “Unbound,” a show that opened earlier this summer on Native American art of the Plains.

“There were always star quilts in progress, moccasins in the works,” Lauren Good Day, one of the featured artists in the show, reflects in a catalog essay. Her life in North Dakota was, and still is, “steeped in culture.”

Known for her marvelously patterned dresses, Good Day’s pictures are dazzling. Drawn on ledger paper, in the Plains tradition that dates back more than a century, Good Day suffuses her work with an arresting clarity. In We Learn from Our Grandmothers, 2012, a group of women, clad in pure blue, red, and green gowns, are encircled by swirls of flowers.

“It honors the women who came before,” Good Day observes, “those who passed on knowledge and continued the arts of our people.”

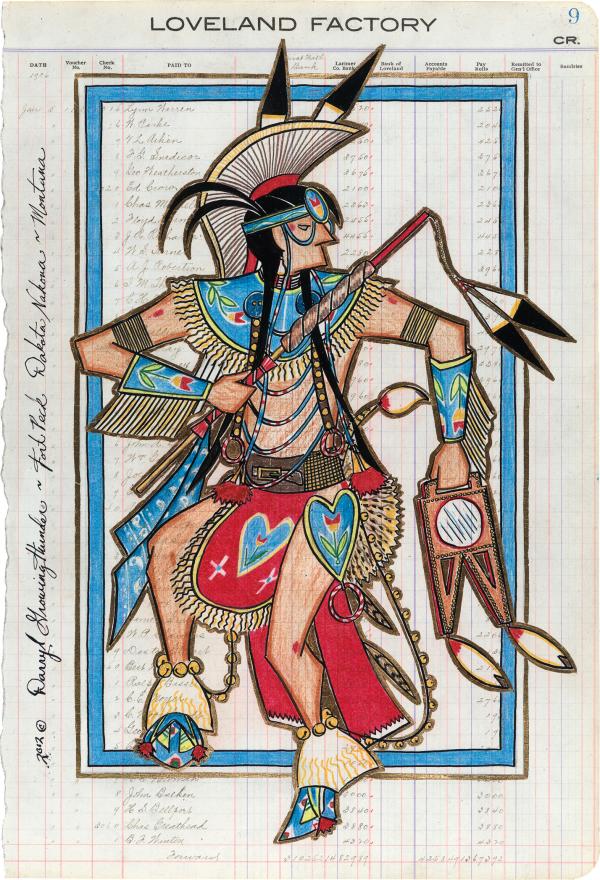

That art is often playful and full of whimsy. Consider Chicken Dancer, 2012, Darryl Growing Thunder’s terrifically detailed picture, the figure’s arms akimbo, imitating a prairie chicken’s mating dance. Following in the practice of many northern Plains tribes, the movement is both rooted in the past and gesturing to the future.

Dwayne Wilcox, of the Oglala Lakota tribe, takes a similar tack. Infused with wit, his pictures present people at a powwow checking their phones, women sitting in lawn chairs, waiting for the dance to begin.

Wilcox is interested in what people do in their off time, before the lights go up. He sees beauty in how we move through the world, every day: “Our lives are just as important as our ancestors’ lives.”

Native American art is “not just in the past,” Her Many Horses contends. In these pictures, powwows and gatherings are depicted with a new and exciting flourish. They are “events for today.”

Anya Montiel (Mexican, Tohono O’odham descent), a curator at the museum, agrees: “Everything is changing, everything is evolving.”

Visitors to the museum sometimes assume that Native art can only be one thing, like pictures of men on horseback. But, Montiel insists, it “can really be anything.”

It can be a beaded purse, as in Elias Jade Not Afraid’s charming work, part of the museum’s collection. Adorned with scalloped-edge tulips, the bag glitters in vibrant reds and robin’s egg blues, set against a crimson ground. The strap, bedecked with brass spikes, is especially striking.

“I was inspired by the evolution of Crow floral beadwork over the generations,” Not Afraid says. His work is bright and endlessly modern, “merging the past with today.”

The past can be heartrending, as in Jane Osti’s 2020 jar, Prayers for Our Sisters. Modeled out of clay, the work bears a blood-red handprint, a symbol of missing and murdered Indigenous women, of violence unseen. Dotted with dogwood leaves, used in traditional ceremonies, the piece has a kind of spiritual resonance. Montiel explains that Osti wanted the work to be a “place where people can send their prayers, where they can reside.”

That place is more nebulous for Teri Greeves. Her 2011 work, Sunboy’s Women, of silk, glass beads, and crystals, is reminiscent of a Kiowa creation story. As the tale goes, a boy, part sun, part human, is orphaned and raised by Spider Woman, a powerful, nurturing figure. Montiel sees in the tale an underlying truth: “The community raises a child when the parents can’t.” In Greeves’s work, Spider Woman is paired with the boy’s birth mother, the two set before a blue and red expanse dusted with stars. Greeves has a light touch, never giving herself away.

Ursala Hudson is comparably bolder, her clothing mesmerizing. We Are the Ocean, Hudson’s 2021 collar, shawl, and apron set, is a dizzying array of Ravenstail weaving, edged with long, tendril-like fringe. The clothing needs to be “activated,” or danced, Montiel explains. At the Renwick Gallery last summer, a Tlingit dancer donned the set and whirled through the museum, twisting and turning to the pounding music.

Hudson takes after her mother, the renowned weaver Clarissa Rizal, who passed away before Hudson completed the work. In Montiel’s words, Hudson “had to carry on this art.”

No less stunning is Jontay Kahm’s Bell Bird dress. The 2022 work, of slate-gray-dyed goose feathers, is electric. Its name is a nod to the loudest bird in the world. The dress, too, is cacophonous, feathers jutting out like a flower in bloom.

Kahm is quickly rocketing to stardom. In February, actor Lily Gladstone sparkled in one of his elaborate creations at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival, its blue-green duck feathers catching the light.

This work is a reminder that Native American art is lush, intricate, and ever-changing. It has within it a “vastness and beauty,” Montiel says, something hard-won and splendidly, ravishingly alive.