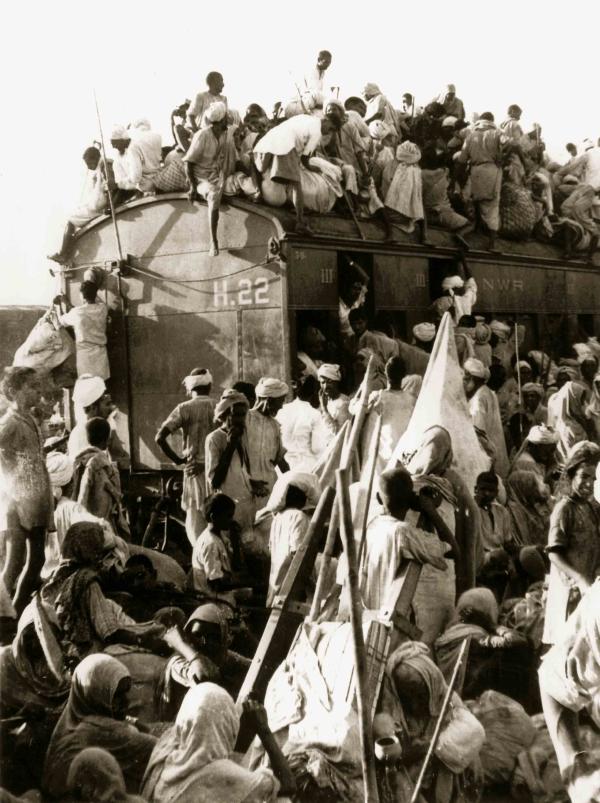

Few Americans know the story of modern India and Pakistan’s chaotic birth in 1947, or the Partition, as it is known, when British forces hurriedly retreated from South Asia. More than 14 million people were uprooted from their ancestral homes and an estimated 3 million perished due to violence, hunger, suicide, and disease. The history books I read in my Florida high school spoke about Mahatma Gandhi’s peaceful marches as a means to independence in South Asia, but never mentioned the bloodletting and the unprecedented refugee crisis caused by the retreat of an empire bankrupted by World War II.

By 1947, about half of South Asia was ruled by the British Crown as “British India,” surrounded by more than 500 indigenous and autonomous kingdoms, many of which maintained a protectorate agreement with the British Empire. As the British departed in the summer of 1947, unable to financially sustain their colonies following the war, the South Asian kingdoms were consolidated with British Indian territories, sometimes by military force, to form two new countries: the Republic of India and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a British barrister, was commissioned to divide the regions of Punjab and Bengal, based on religious majorities: Muslim-dominant areas went to Pakistan and Sikh/Hindu-dominant areas went to India. Unable to quell the independence movement and growing sectarian violence, the British accelerated the transfer of power to less than six months, leading to a complete breakdown in society. The sudden transition from an imperial colony to a democracy led to mass violence as locals vying for power sought to “cleanse” their newly acquired constituencies, supported by far-right religious groups whose agendas were eerily similar to early twentieth-century nationalists in Europe. Gangs of young men eyed an opportunity for economic gain during the chaos, participating in organized looting and using religion as an excuse to target vulnerable, newly minted “minority” groups whose ancestral lands were now on the wrong side of a border.

Partition led to an unprecedented mass migration and refugee crisis. Despite the scale of the upheaval and continued repercussions of Partition, it was a forgotten history six decades later in 2010 when we began our work of building the 1947 Partition Archive, a crowdsourced oral history repository that preserves more than 10,300 survivor interviews from around the world. I was motivated to bridge the gap between official histories and the folk histories we heard in our families. My own grandparents’ story of migration from Lahore to Amritsar (and then Delhi) seemed unfair and unnecessary. They, and millions of others, were uprooted from their homelands because of miscalculated decisions by a few leaders. “The only solace we had was that we were in this together,” one interviewee recalled.

The oral histories are challenging commonly held perceptions of Partition history and our global memory of colonialism in surprising ways. The stories reveal how the transition of power in 1947 was haphazard on multiple levels. One witness from Larkana in the Sindh Province remembered, “A British officer who was summoned to leave his post quickly picked out my father and handed over his prestigious civil services position.”

Other stories poignantly capture the psychological scars of Partition: Ali Shan, now a happy grandfather who enjoys spending his Sundays leading hikes in the San Francisco Bay Area, was orphaned in 1947. He watched a mob murder his family and became the sole survivor of the attack. He lived in refugee camps all alone as an eight-year-old boy and described his emotional journey of overcoming trauma by forgiving his family’s murderers. When he shared his story with our volunteers, it was the first time he had told it, as the memory was too difficult for him to recall for family and friends.

When we began this work in 2010, the last generation of Partition witnesses were aging, and time was running out to capture their memories. We devised a crowdsourcing protocol to collaborate with the public in documenting oral histories. New digital tools, such as emerging cloud-computing technologies and social media features, enabled fast and frugal documentation from across the globe. We began posting unedited images of elders being interviewed in villages and towns across the world, inspiring thousands to join us. The process accelerated with the proliferation of smartphones with video capacity.

By 2016, the 1947 Partition Archive Facebook page had ballooned to one million followers, who were interacting with our oral history posts more than ten million times a year. Today, more than 7,000 individuals have trained at our free online oral history workshops held biweekly since 2012. They have gone on to help preserve more than 10,000 oral histories of Partition witnesses. Makers of several films, including blockbuster Bollywood numbers such as Bharat and Bhaag Milkha Bhaag, as well as the BBC documentary My Family, Partition and Me, have consulted the 1947 Partition Archive’s public content and oral history collections. Exhibits such as “Stories in the Metro,” held in Delhi’s popular Mandi House Metro station for two years, introduced memories of Partition witnesses to more than half a million riders per day. Meanwhile, exhibits such as “Refugees of the British Empire,” supported by California Humanities and held at the archive’s Berkeley location, exposed the local public to this tragic chapter in world history. An ongoing collaboration with Stanford University Libraries will make the collection accessible to scholars via online streaming.

At “Refugees of the British Empire,” audiences were introduced to the lesser-known South Asian battlefields of World War II through an unforgettable story: California resident and triple refugee Hardeep Singh, as he is called for privacy, narrated his family’s great escape on foot when Rangoon (Burma, British India) was bombed by the Japanese Army in December 1941. Singh’s family walked for more than a month through thick jungles in long lines formed by thousands of families on the same journey. “I was just a child, but I remember details vividly. . . . Many perished along the way,” he noted in Punjabi. Singh’s family members, like the others, were considered foreigners in Rangoon, hailing from the western reaches of British India. They traveled nearly 2,000 miles to safety in their ancestral village in West Punjab. However, it wasn’t long before unrest reached their doorstep again in 1947. They were driven out by violent mobs and had to flee with only a moment’s notice. Once again, they joined long caravans of people walking, making their way east to the regions that would become India. They walked for more than a month. Similar caravans traveled in the opposite direction. As for Singh, following another episode of sectarian violence in Punjab in 1984, he fled with his family, finding refuge in the United States.

“It can happen here also,” Singh noted at the end of his interview, referring to the possibility of communal violence, leaving us to ponder lessons the world hasn’t yet learned from the 1947 Partition. Selective memories of the 1947 trauma overshadow memories of peaceful and uneventful coexistence before Partition. Oral histories give equal weight and context to both kinds of memories, providing an opportunity for critical reflections that challenge popular assumptions at the core of modern social conflicts. The archive is one way to reconcile the gap between folk histories and official histories, so that we may truly heal our historical wounds.