On January 6, 2021, the world watched in horror as an angry crowd stormed the U.S. Capitol building, trying to intimidate Congress into overturning the results of the presidential election.

Even as the drama unfolded, I couldn’t help recalling another moment when a crowd attacked an iconic public building: July 14, 1789, in Paris, France, when a crowd stormed the Bastille. That event marked the beginning of the French Revolution, a subject about which I have written and taught for more than four decades.

The storming of the Bastille set a precedent: For the first time in modern history, ordinary men and women, through their collective action in the streets, ensured the creation of a constitutional system of democratic government. Within a few years, however, the French Revolution would also show that crowds could be dangerous, even to governments that claimed to represent the will of the people.

For centuries, France, like almost all major countries of the world, had been governed by a hereditary monarchy. The church, schools, and other authorities assumed that society could function only if common people left government to those who were chosen —by God or tradition—to direct it. To those in power, the lower classes were “the rabble,” “the mob,” an irrational force to be kept in awe by the police, the courts, and, if all else failed, by military force. The peasant farmers, artisans, and laborers who made up more than four-fifths of the population in France in 1789 mostly accepted the status quo, which seemed unalterable. Most of them had enough to do just to make a living.

Even before 1789, however, ordinary people in France and other places knew that they did have some power if they acted together. The memoirs of the French glassfitter Jacques Ménétra, one of the few working people of the time to keep a record of his life, recount many times when he and others joined together to confront the authorities. When flour prices soared, making bread too costly for poor families, crowds, often led by women, seized grain shipments and forced merchants to sell their goods at what the population considered a fair price. Ménétra and other artisans knew how to act together to pressure their employers for higher wages and to guard their jobs from outsiders who might undercut their wages. When the French king tried to get the courts to authorize new taxes, law clerks roused urban populations to demonstrate against these violations of traditional rights.

In 1789, French King Louis XVI, facing an unprecedented financial crisis, was compelled to raise taxes. He summoned the Estates General, a long-forgotten elected assembly that had not been convened in 175 years. The king hoped that deputies chosen by his subjects would agree to raise the taxes to stave off bankruptcy. The elections were an unprecedented opportunity for the population to express their opinions. The same local assemblies that chose deputies for the Estates General also drafted cahiers de doléances, lists of complaints and demands for reform. The cahiers left no doubt that a majority wanted constitutional limits on the king’s powers, protections for individual rights, and an assembly chosen by voters to make the country’s laws.

Louis XVI, who had been raised to think he was divinely chosen to rule his kingdom, could not bring himself to accept such drastic changes. When the elected deputies of the Estates General renamed themselves the “National Assembly” to assert their claim to be speaking for the entire population, the king prepared to use force to oppose them. Army regiments were brought from France’s frontiers to the capital. Fears mounted that they would be used to dissolve the Assembly and overawe the population, whose support for the deputies was unmistakable. On July 11, after weeks of tension, the king acted: He dismissed his chief minister, Jacques Necker, who had been trying valiantly to broker compromises. In the National Assembly, deputies passed defiant resolutions and braced themselves for arrest or worse.

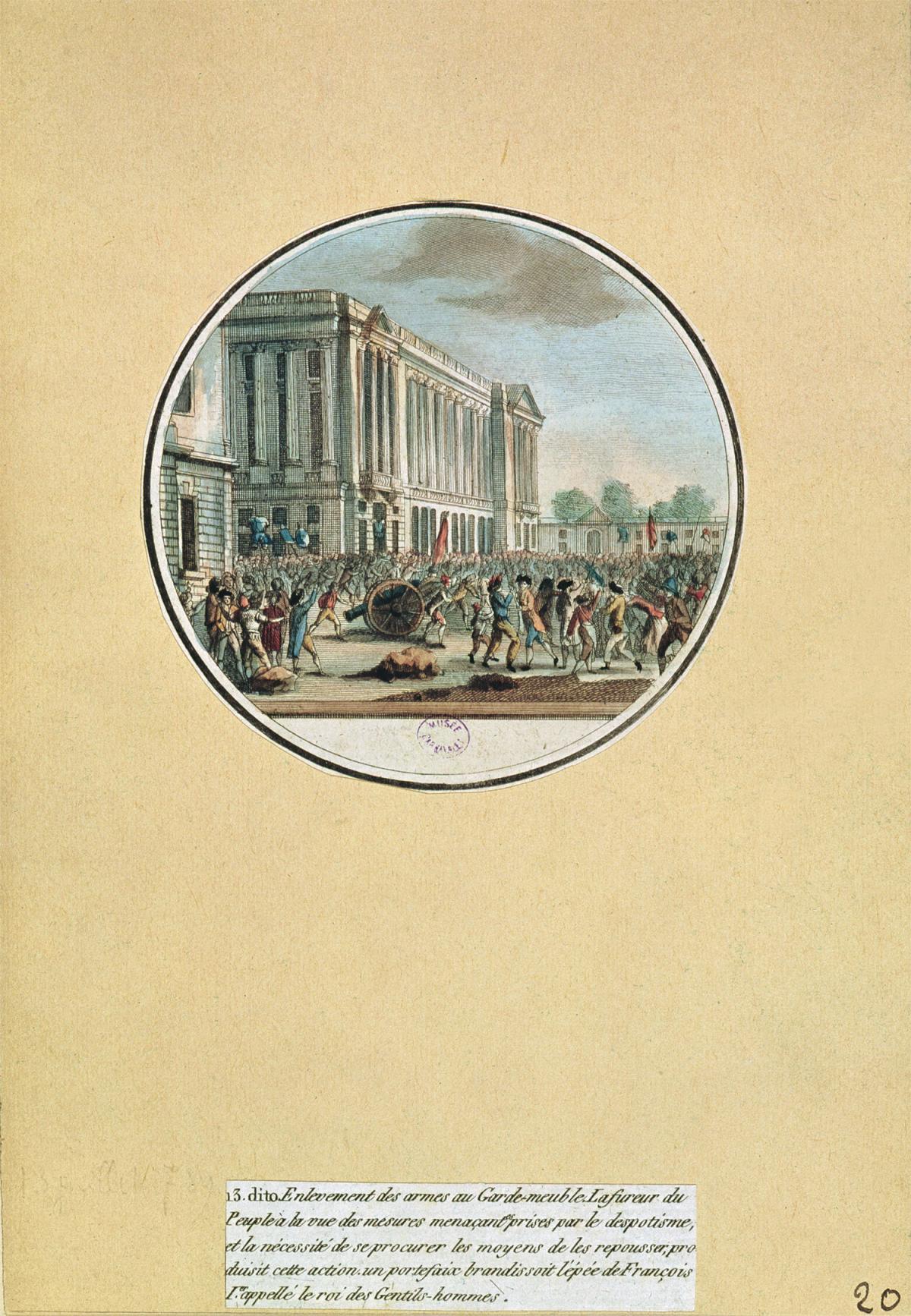

At the news of Necker’s dismissal, the population in Paris poured into the streets. Crowds formed and attacked symbols of authority, starting with the barriers at the entrances to the city, where much-resented taxes on foodstuffs were collected. When royal troops charged a large gathering in the Tuileries park in the center of Paris on July 12, the crowd fought back, hurling stones at the soldiers. Alarmed commanders warned the royal court that their soldiers weren’t willing to open fire on their fellow citizens, but rumors of impending military action rubbed the population’s nerves raw. All through the day of July 13, large bands roamed the city, searching for arms and ammunition to defend themselves against an assault they expected to come at any moment.

On the morning of July 14, attention turned to the Bastille, a fortress whose medieval towers commanded the working-class neighborhood of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. Completely obsolete as a military fortification, the Bastille had been used as a prison, but by 1789 it was rarely employed even for that purpose. It remained, however, a symbol of arbitrary royal power. And that day the Bastille attracted the crowd because it housed a store of gunpowder, which the citizenry needed if they were to fend off an armed attack. For several hours, the small detachment of soldiers defending the Bastille held off the crowd, killing about 100. Rather than deterring the people, the fortress’s resistance enraged them further. Led by some soldiers who had taken the side of the people, the crowd finally broke down the fortress’s main door and the garrison surrendered. The collective action of the ordinary men and women who made up the crowd—members of both sexes took part—had overcome the power of the king and his army.

As news of the dramatic events in Paris arrived in Versailles, about 12 miles away, the National Assembly deputies became increasingly nervous. Many of them feared this outbreak of violence would furnish a pretext for the king to send in his troops. A few years earlier, in 1780, a rampaging mob in London, just across the English Channel, had set fire to buildings, causing great damage and several hundred deaths. It was both a relief and a surprise when the deputies learned that the crowd, although it had massacred the commander of the Bastille and the acting mayor of Paris, was demanding above all that Louis XVI withdraw his soldiers and accept the Assembly’s authority to create a new national constitution. Through their collective action on July 14, which was followed by a wave of popular actions nationwide, the people of Paris settled the contest between the king and the people’s representatives.

The storming of the Bastille was a victory for the idea of representative government, but it also established a precedent that would shape the subsequent course of the French Revolution. Mass demonstrations and assaults on government buildings became so frequent during the revolution that they acquired their own name: They were called journées or “days,” many of which marked turning points in the movement. On October 5 and 6, 1789, a mostly-female crowd marched from Paris to Versailles, demanding that the king and the National Assembly take action to lower the price of bread and that they relocate to Paris, where the people could pressure them more easily.

As the politics of the revolution became more radical, journées became more frequent and, often, more violent. On June 20, 1792, thousands of armed demonstrators invaded the royal palace, where they held the king prisoner in his own home for hours. Less than two months later, on August 10, 1792, amid rumors that the king and queen were supporting the foreign armies that were invading France, armed battalions of the revolution’s citizen militia, the National Guard, stormed the royal palace of the Tuileries. The elected Assembly thus had no choice except to declare the end of the French monarchy. In the ensuing months, that Assembly itself was replaced by the National Convention, the first legislative body to be chosen by universal male suffrage.

Even an assembly chosen by the people was not immune to the power of the crowd, however. From May 31 to June 2, 1793, National Guards and other members of the population laid siege to the meeting hall of the National Convention and forced the deputies to expel some of their own members, ensuring the triumph of Maximilien Robespierre’s radical political faction. Robespierre’s allies celebrated the crowd action that had brought them into power. The new democratic constitution they passed after their victory proclaimed, “When the government violates the rights of the people, insurrection is, for the people and for every portion of the people, the most sacred of rights and the most indispensable of duties.”

The overthrow of Robespierre on 9 thermidor Year II (according to the revolutionary calendar, also known as July 27, 1794) was an unusual journée. For the first time, the population did not respond to calls to use its collective power to defend a man who claimed to be defending its rights. As the surviving revolutionary legislators plotted a more conservative course and as economic distress reached a peak in early 1795, two massive demonstrations, the journées of germinal and prairial Year III, rocked Paris. The journée of 1 prairial, launched mainly by women, was probably the largest popular mobilization of the entire revolutionary era. The crowd flooded into the Convention’s meeting hall, killing one deputy and paralyzing the proceedings for hours as they pressured the other deputies to accept their demands. A few months later, on 13 vendémiaire Year IV, a counterrevolutionary journée broke out. Demonstrators hoping to bring back the monarchy marched on the Convention, claiming that it had rigged the elections held to replace it. A young army general, Napoleon Bonaparte, played a crucial role in fighting off the assault. Four years later, he would organize the coup d’état that put him in power and signaled the end of the French experiment with democracy.

The French Revolution demonstrated that when common people united, their collective actions could bring about results. Without the storming of the Bastille, France’s revolutionary experiment with democracy would have been quashed at the outset. But crowd action could also backfire: The journée of May 31 to June 2, 1793, cleared the way for a revolutionary dictatorship that curtailed citizens’ rights, and the hunger-fueled invasion of the Convention on 1 prairial Year III led to a conservative exercise in voter suppression, as the deputies hastily enacted a new constitution that deprived most of the population of any meaningful voice in elections. The counterrevolutionary journée of 13 vendémiaire Year IV showed that, under the right circumstances, a crowd could be roused to demand the end of democracy.

Over the course of the centuries since 1789, popular crowds have intervened to challenge governments many times, often reenacting the scenario of the storming of the Bastille by seizing symbolically important government buildings. In the United States, born of a revolution just a few years prior to the French movement, such actions have been rare, but recent events have shown that they are not impossible. Democracy proclaims that the legitimacy of governments is dependent on the will of the people. Elections are intended to provide a safe and generally accepted mechanism for the expression of that will. When people gather to form a crowd, however, they can persuade themselves that mob violence is a legitimate way of channeling their will. It’s what makes crowds so powerful, and, sometimes, so dangerous.