The Missouri photo workshop poses and answers an interesting question for our image-drenched media. What can photojournalism do? Does it exist only to capture the big drama of elections, crime scenes, and war zones? Or can it also help us monitor smaller changes in the world?

Known as MPW, the workshop starts with around 40 photographers from different parts of the globe, who are shipped off annually to a small town in rural Missouri. The photographers immerse themselves in the town for one week to find a compelling story about rural life before having it approved by a faculty of photojournalists—all before they press the shutter button on their cameras. Even then, the photos cannot be posed.

The degree of difficulty runs high, but the sleepless nights, failed story ideas, and obsessions over the perfect shot result in heartwarming photos showing the lives of people removed from bustling society. The MPW impacts how townspeople view their homes and how people around the nation view the rural Midwest, which is often underrepresented in media.

The MPW was founded by Cliff Edom, who headed the first photojournalism department at the University of Missouri, and his wife, Vi, in 1949. It has been around for 75 years, with each new workshop adding to the repertoire of photos. The result shows a progression of rural life from just after WW ll to the present day.

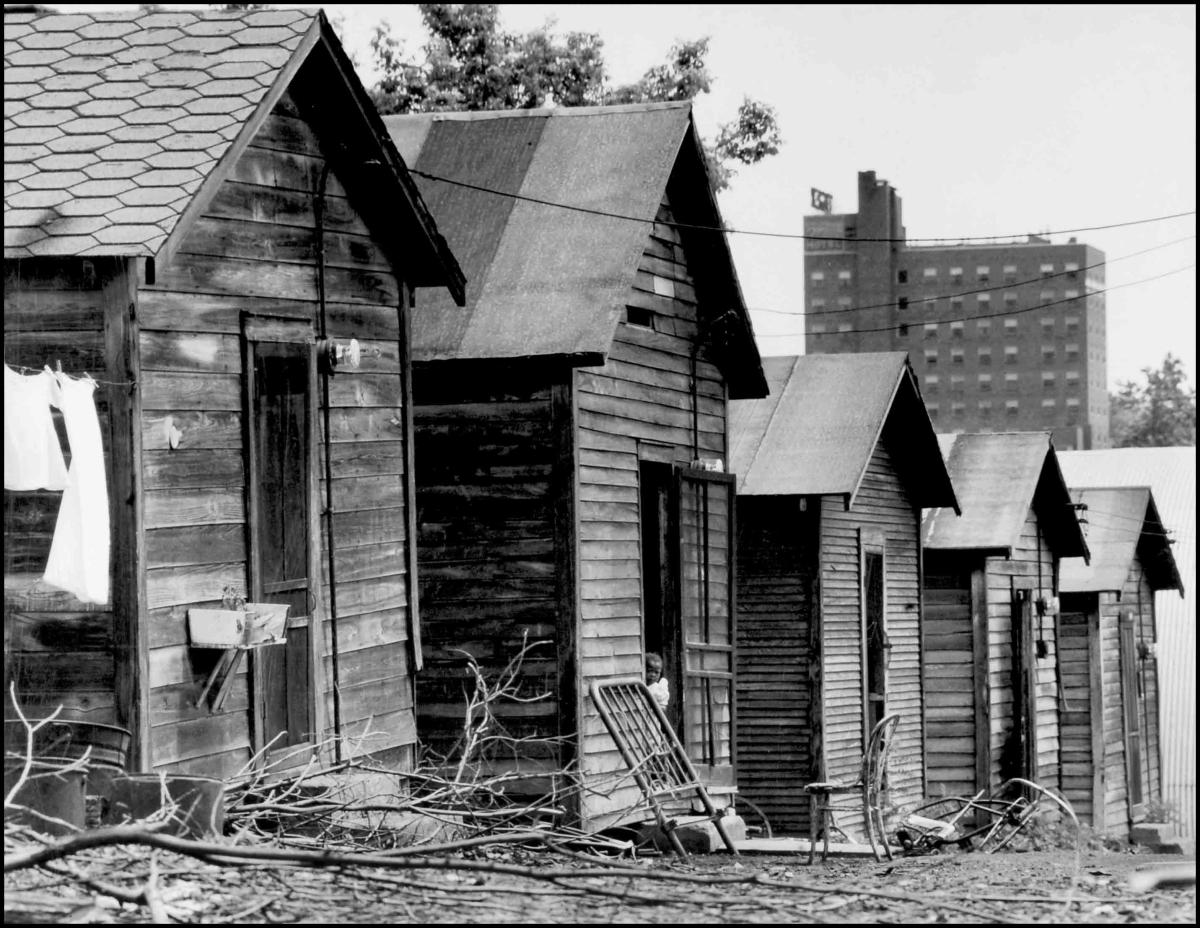

During the 1930s, the Great Depression and Dust Bowl produced an overwhelming amount of rural poverty. President Franklin D. Roosevelt commissioned the Farm Security Administration to document the devastation to support his New Deal legislation, which was struggling in Congress at the time. According to Jim Curley, a former codirector of MPW, the FSA hired a small group of photographers to crisscross the country and capture the catastrophe from dust storms in Oklahoma to migrant camps in California.

Edom believed these photographs had a profound impact on not just American government, but society as well. In 1949, he teamed up with Roy Stryker from the Farm Security Administration to hatch a plan to organize the first MPW.

“Small Towns, Big Stories” was an exhibition at the State Historical Society of Missouri in Columbia to mark the project’s 75th anniversary. It ran from September 2023 to February 2024. Curiously, the exhibition did not feature pictures in chronological order. Instead, MPW director Brian Kratzer worked with fellow curators David Rees and Curley to group the photos into themes: They each took a quarter century of photos and narrowed the selection to 10 to 15 options. Then they joined forces and distilled the groups down to the final photos for the exhibition.

“Sometimes you can draw more by the pairings of two photographs,” says Kratzer. “The X-factor, or the third effect, is when you put two photographs together that don’t belong together. But then there is a deeper meaning by seeing the two of them together.”

Color hierarchies and sizing of photographs play into this curation as well, making the exhibit so aesthetically pleasing that it can hold one’s attention for hours: “I am always drawn to chronological [exhibits],” says Joan Stack, the curator of arts collections at the historical society. “However, the mixture of color with black-and-white photos and mixtures of different time periods enlivens the exhibit.”

One photo taken in Sedalia, Missouri, shows a Black elementary school girl laughing with her friends, who happen to be a sea of white classmates. The photo is black and white, and the monochrome element silences all distractions. Taken in 1980, Sedalia’s public schools were just beginning to desegregate. The little girl pictured is the first Black student at her school, but she seems to be integrating with ease. Reese says that the girl, who is now grown, messaged the MPW on Facebook and confirmed that the photographer did capture the essence of her journey to a new school—she was enjoying herself in that picture.

Opposite that image, there is another monochrome taken in Sedalia at the same workshop, but by a different photojournalist telling a different part of the story. Three Black women sing into a microphone at a recreational center, and the caption says that one of the women was a well-known advocate in Sedalia for desegregating their schools. With 40 photographers trying to represent rural life in a community that was home to around 20,000 people, there are natural connections, especially when the event is as momentous as integration.

One of the reasons Rees grouped the photographs according to themes is that small towns in Missouri have similarities. There is an entire panel in the exhibition dedicated to main streets in small towns, and at least five photographs were taken in barbershops. Both of these sites are hubs for townspeople to interact. There are also photos of various types of family life, such as a young mother living in a mobile home with five small children, or a nuclear family reading the Bible during homeschool. Multiple photographs feature widows sitting outside their lonely homes. “The land, Main Street, and identity were the three themes we had to balance,” says Rees.

In another photograph, a mother takes care of her grown daughter who is dying from cancer. That photojournalist was having trouble finding a subject and, on a sweltering day, skipped in front of a woman who was buying cat food at a grocery store. After he checked out, he realized his rudeness and apologized to the woman, helping her bring her groceries to her car. By chatting with her, he discovered a story to document. In the MPW, connecting with the people comes before the story, the story comes before the photography.

The MPW is a “rite of passage” for photojournalists, but over the years it has drawn different kinds of photographers. At the start, many of the photojournalists had recently fought in a war, while others were housewives. Now, the photographers are freelance and often concerned with the conservation of land. Just as the photographers are evolving, this project continues. Next year, and the next year, and so on, a new crop of photographers will detail a new spot of Missouri rural life, their visions and stories quietly documenting places and people not often noticed by history.