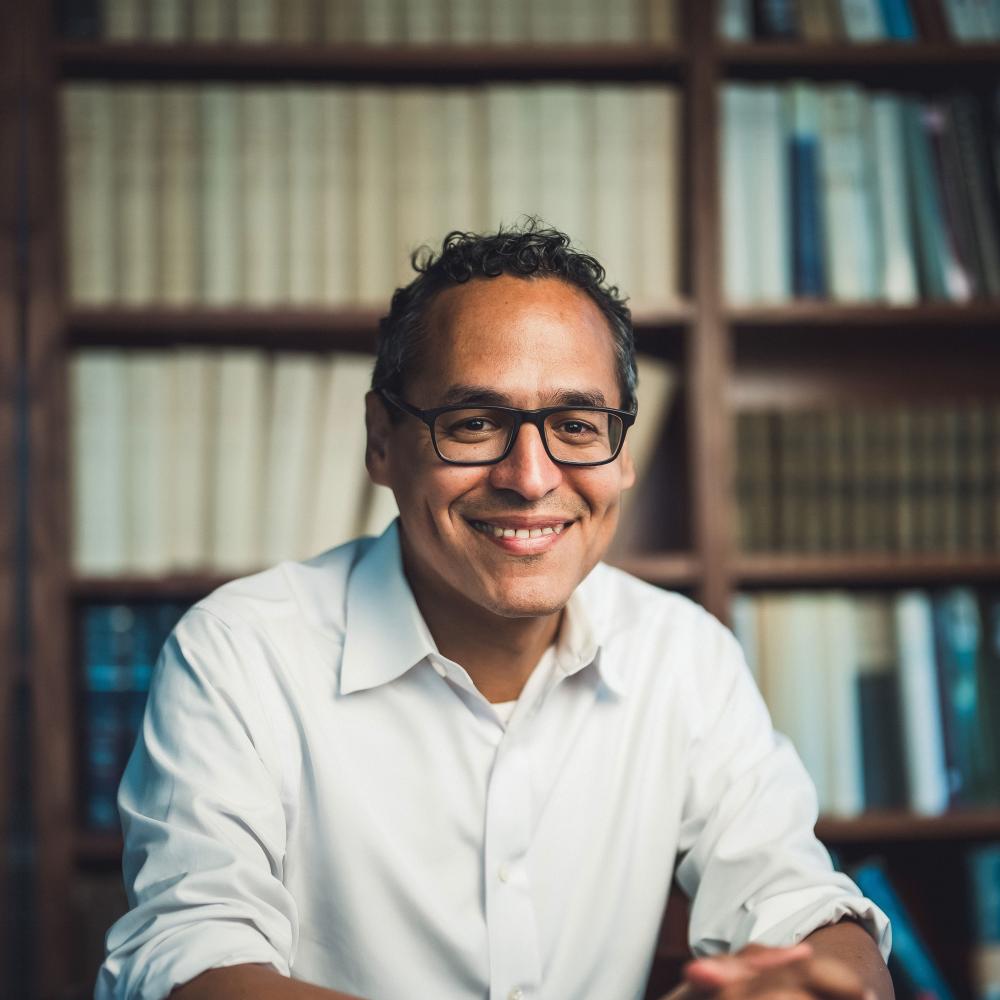

As a teenager and a recent immigrant, Roosevelt Montás enrolled as a freshman at Columbia University. Like all undergraduates, he was required to complete a two-year core curriculum focused on great books from Homer to Toni Morrison. After graduation, Montás went on to teach in this program, and from 2008 to 2018 he served as the director of the Center for the Core Curriculum at Columbia. Now, in a critically acclaimed book, Rescuing Socrates: How the Great Books Changed My Life and Why They Matter for a New Generation, Montás sets out to celebrate this form of liberal education and say how it benefited him personally.

HUMANITIES: Your book is in part an immigrant’s memoir. So let me start by asking, When did you come to the United States and why?

ROOSEVELT MONTÁS: I came to the United States in May of 1985, a few days before my twelfth birthday. I am from the Dominican Republic, from a rural town in the mountains. And we came, the simple way to put it is, because we had a chance to. In probably most Latin American countries, that same logic obtains. If you have a chance to go to the United States, then you do, particularly if you are poor. If you are upper class and have any kind of comfortable life, then it may be less attractive, but that was not the case for us.

My mother had come ahead of my brother and me, by a few years, on a green card, which gave her the right to petition for her children to join her. And that was the whole point of her coming, having been sponsored by her brother, my uncle, who was a naturalized citizen.

So the answer to the why question is “because we could.” It’s widely understood and accepted that there will be more opportunities for a better life as an immigrant to the United States than as a poor person in the Dominican Republic.

HUMANITIES: You have a key passage about how people from the Dominican Republic react to what Americans throw out with their garbage. Can you describe this close encounter of cultures and how you found treasure in someone else’s trash?

MONTÁS: There’s a very large Dominican community in New York that retains close links to the Dominican Republic and goes back frequently. So in the Dominican Republic you always hear details about how you can just walk around the streets of New York and find all kinds of treasure—appliances, furniture, clothing, just about every conceivable thing—often in very good condition, in people’s garbage.

It’s kind of unbelievable from the point of view of people in the Dominican Republic that this is the case, that there is a place of such affluence that people are just throwing away things because they’re tired of them or because they require minor repairs.

So there is a common practice among Dominican immigrants of going out on garbage night and scouring the neighborhoods. People will pick up stuff and sometimes send it back to the Dominican Republic or fix it and sell it. In my case, the great treasure I found was a set of books that my neighbors had thrown away.

I was a sophomore in high school. My English wasn’t really up to speed, but I managed to pick up two volumes from a gorgeous series called the Harvard Universal Classics. I picked up a volume containing a few of Plato’s dialogs and a volume containing some of Shakespeare’s plays. This was a fortuitous and transformative find for me. Reading Plato not only opened up a whole world, it also occasioned a key relationship in my high school with a teacher who became a close mentor and a close friend. He saw me reading the book in the hallway and engaged me about it. That was the beginning of a relationship that turned out to be quite crucial in my life.

HUMANITIES: The dialogs of Socrates must have been difficult for you to read.

MONTÁS: Yeah, but there was something immediately appealing about the book. I was lucky to find the dialogs that I did. This collection covers the last days of Socrates. He is on trial, accused of introducing new gods to the city and of corrupting the youth. What he is actually doing is practicing philosophy. He makes his defense, is found guilty, and is condemned to death. Then there is a dialog in which a friend tries to get him to escape from prison. Socrates refuses. Then there’s a dialog that records his final day, in which he drinks the poison and dies philosophizing to the very end. It’s an extremely compelling and gripping human story. And I think if I had started in some other place, I would not have made any progress, but this story really, immediately, gripped me.

Then seeing me read this book drew interest from a teacher, John Philippides, who was himself Greek and had had a classical education and was so excited that this young person was interested in Plato and in Socrates. He helped me digest and absorb what that book was about.

HUMANITIES: You have a nice line about him, saying you could see the “teacher-fire in his owl eyes.”

MONTÁS: He was never my actual teacher, he never taught my class. But we would meet after school and during lunch periods. I remember one time, during the exam period at the end of the year, he took me to lunch at a nearby diner, because the school cafeteria was closed. It was one of the first times I had been to a restaurant, and it was just such a fascinating thing to be at a diner, eating lunch with a teacher.

HUMANITIES: Now, how did you find yourself as a freshman studying at an Ivy League college just a few years later?

MONTÁS: It was a struggle and in some ways an accident. I had experienced this profoundly traumatic uprooting from my broader family, from my culture, my language, my friends. I then landed in a place of anonymity and marginality. By the time I was graduating high school, I knew I wanted to go to college but I could not countenance being uprooted again and going to some random place. I would stay in New York and the place I had come to know as home. Mr. Philippides encouraged me to apply to Columbia. He was the only person to read my personal statement for the application. Otherwise, I was all on my own and was just very lucky to end up at Columbia.

HUMANITIES: Okay, so now we’re entering the next period of your life, where you begin to study the liberal arts more formally.

MONTÁS: Columbia is famous for its core curriculum, which is a required set of courses for all undergraduates in, roughly speaking, the classics. Every first-year student takes “Literature Humanities,” which begins with the Iliad, followed by the Odyssey, followed by ancient Greek plays and the histories of Herodotus and Thucydides. It’s a yearlong course. Students meet in small groups with a professor. It’s a profoundly transformative experience. You do it again sophomore year, now reading philosophical texts beginning with Plato’s Republic, and then there is a one-semester art course and a one-semester music course. These courses gave me the intellectual architecture, a kind of infrastructure upon which my whole education developed.

That was the liberal education at Columbia. It is liberal because it is not oriented toward any career or occupation. It is a common general education.

HUMANITIES: You make a comment about the importance of the teacher’s personality to the chemistry in the classroom. Can you talk about that a little bit?

MONTÁS: Liberal education addresses itself to the condition of every individual as a developing, unfolding agent who is autonomous, that is, self-governing. Every individual has the capacity—in fact, the inescapable task—of organizing his or her own life according to a subjective conception of the good. That is the situation with which a liberal education concerns itself. So it teaches, in the profoundest sense, how to be human or rather it facilitates a process of full human development that takes place in relation to others. The vehicle for liberal education is dialog, interaction, and conversation with other individuals. The role of the liberal arts teacher is absolutely fundamental to this conversation. Sometimes I say that liberal education happens by contagion. You are exposed to minds, not just the teacher’s, but those of your peers as well, who are engaged in the same project you are, minds who are engaged in the investigation of questions and issues that concern us as human beings in the deepest way, questions of meaning, questions about what really matters in life. Who am I? What is worth pursuing? Whereas a professional education might teach you how to be a great professional, a liberal education makes you wonder what kind of profession is worth pursuing and what being great at a given profession actually means.

The experience of liberal education, going back to Socrates as an example, is profoundly subjective and interpersonal. Plato’s Symposium speaks about the erotics of learning, the way that desire is involved in education. To quote a colleague and a friend at Columbia, humanities teaching is the “noncoercive restructuring of desire.”

Plato elsewhere, in the Republic, says that teaching concerns turning students’ attention toward knowledge, not putting knowledge in the students, but turning their vision in a particular direction. All of that process of reorienting the soul, of restructuring desire, happens through an almost mystical connection with other individuals, rather than through a passive reception of knowledge.

The books are extraordinary vehicles for stimulating this process, but you don’t get a liberal education simply by reading a book. You have to talk about the book with someone else who is engaged in the same process of exploration you are.

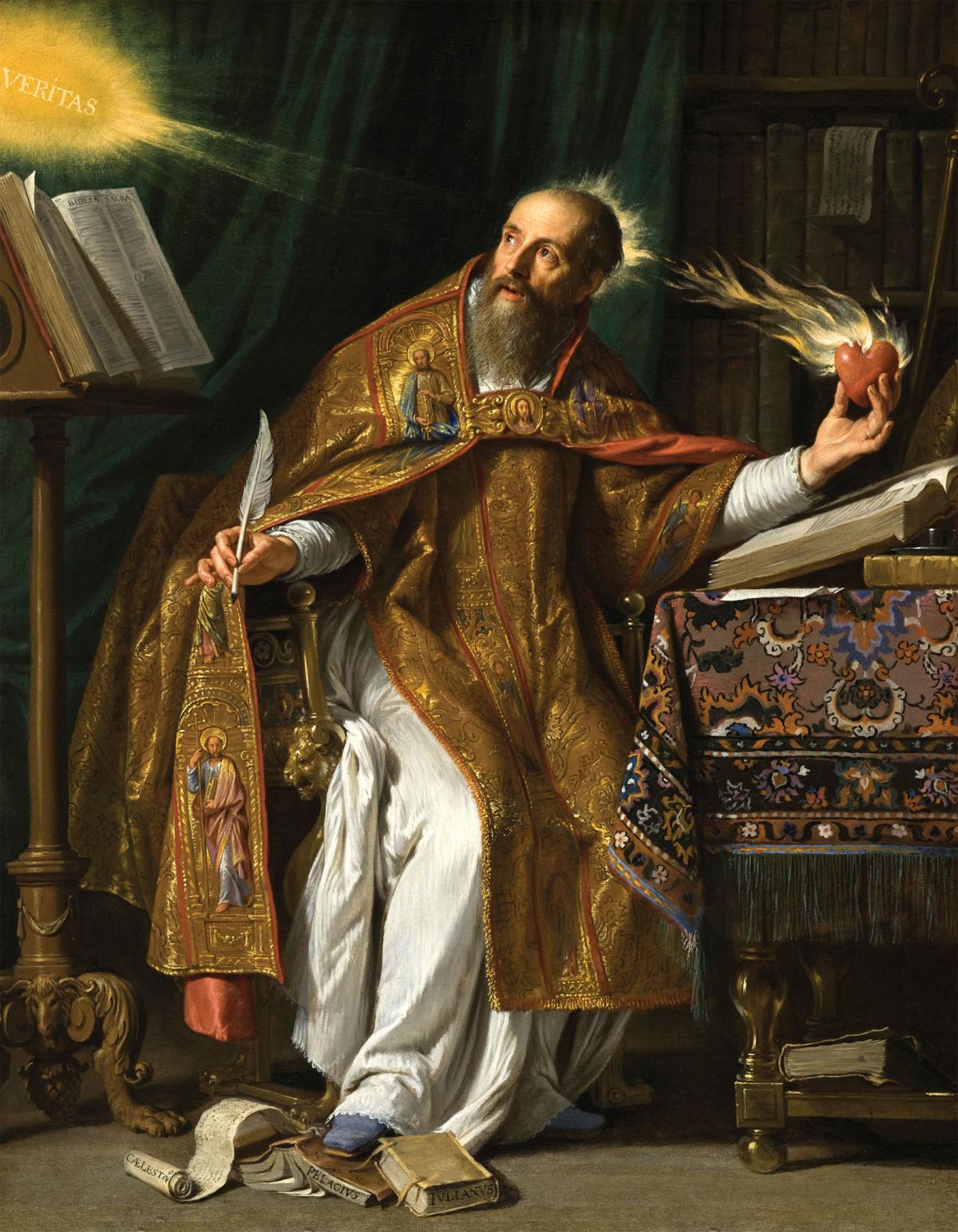

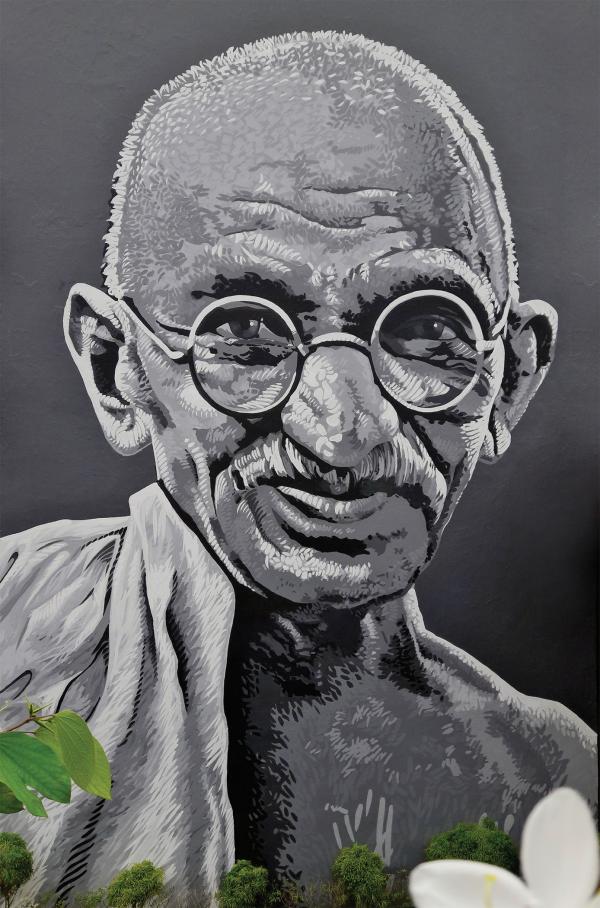

HUMANITIES: Your book is organized around four major thinkers: Socrates, Augustine, Freud, and Gandhi. I’m sure it could have been written around a lot of different writers and thinkers. But those four are special to you. Why?

MONTÁS: Those four authors happen to have had an outsized impact on my own development. They found very fertile ground in me when I read them and had an illuminating and transformative impact. In a way, that is just an idiosyncrasy of my own personal history.

Another reason why I chose those four is that those writers strike me as particularly suitable for liberal education. They are in some sense exemplary of the kind of texts that are conducive to a liberal education.

The last thing I would say about those four writers is that they are all explicitly concerned with self-knowledge. They were all looking into their own minds as a way to understand the whole world and their own place in it.

Socrates is famous for saying that the unexamined life is not worth living. Augustine, whose Confessions is probably the first autobiography ever written, tells the story of his own trajectory toward God. Freud, in obvious ways, is deeply concerned with the workings of the mind, including his own. And Gandhi sought, as he put it, to see God face to face, not in another life, but in this one. So all these authors are engaged in a quest for self-knowledge that is paradigmatic of liberal education.

HUMANITIES: One book that we might compare yours with is The Closing of the American Mind by Allan Bloom, published 35 years ago. Is this a book that holds any special meaning for you?

MONTÁS: I only came upon Bloom’s book in recent years and can’t say it’s had a direct influence on my thinking, though there are some deep similarities. I think I have a looser conception of the canon than Bloom does, but there is certainly much about his argument and his understanding of liberal education that I agree with.

HUMANITIES: One thing I noticed is that, like Bloom, among others, you take an interest in the character, I might even say souls, of today’s students. But you defend today’s students against the common accusation that they are like so many snowflakes, fragile, self-regarding, and under the illusion that each one of them is unlike any other. In your experience, what are the kids really like?

MONTÁS: As long as people have been writing things down and thinking about society, they have been condemning the current generation of youth as morally fallen. There is something almost ritualistic about pointing to the current generation of youth as the latest instance of our societal depravity and degradation.

Today’s youth are not different from previous generations in their zeal, their sincerity, their intolerance for hypocrisy, their idealism, and a certain unnuanced striving for a better world. Certainly, there are specific things about contemporary young people that are unique. They have grown up in a media environment, an information environment, that is unprecedented. They face a set of stimulations and distractions that are unlike any we have seen before, and that has an impact on the kind of individual you’re dealing with. But I don’t think that youth today are fundamentally different than in the past. I have certainly not experienced them as especially self-absorbed or fragile.

The vocabulary they use to express their discontent is drawn from the broader culture, so they are different in that way too. We have medicalized suffering, including psychological pain, in a way that influences how young people today express themselves and seek relief, but those changes are not being driven by them. That’s just the society in which they’re coming up.

HUMANITIES: At one point in your life as a grad student, you founded a program to teach English as a second language to recent, Spanish-speaking immigrants. Can you describe this adventure and what it taught you about teaching?

MONTÁS: When I was in graduate school, I started a program, in Washington Heights in upper Manhattan, to teach adults English as a second language. The experience of having learned English was still very present in my mind, and the sting of being linguistically locked out of the broader culture was still fresh in my mouth, as it were.

We met in the evenings twice a week for three hours each evening, and it was absolutely an extraordinary experience. They were all adults. Most of them were taxi drivers or service workers. Some had very limited literacy, even in in their native Spanish. I was astonished to see them develop and acquire a degree of agency that they did not have, simply by mastering the language.

At the same time, I was teaching Columbia first-year students expository writing, and the contrast was very illuminating. Both students were being equipped with skills to transform the reality in which they lived, but with entirely different needs and life circumstances. I think of this as the most satisfying teaching I’ve ever done because I wasn’t just teaching my ESL students how to express themselves. I was giving them the tools to take the reins of their life in America, I was giving them tools to become social agents in the society where they lived. And we grew very close, the students and I. They were mainly Dominicans, and it was a delight for them to know somebody who was a PhD student at Columbia, who was one of them. And it was a delight for me to open up a little bit of that world to these students.

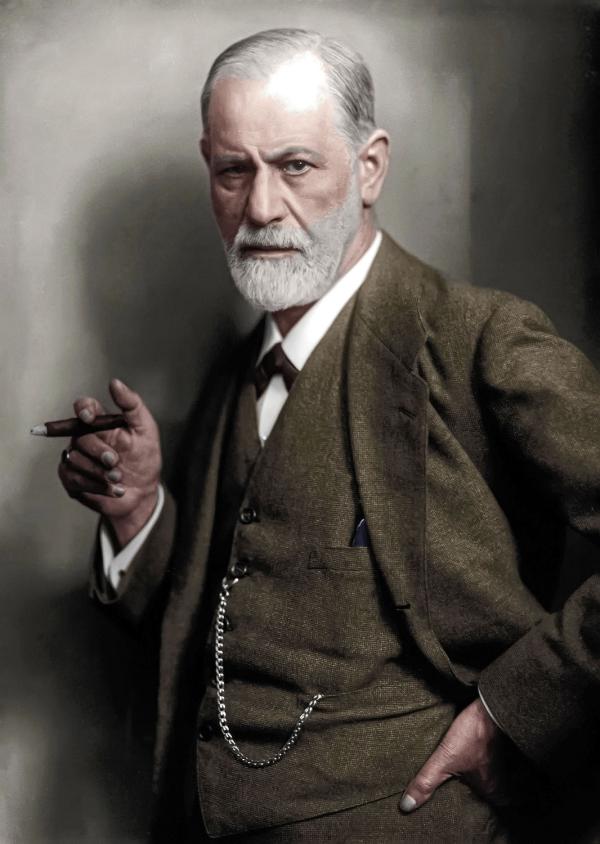

HUMANITIES: In the discussion of Freud, you describe your own personal experience as a five-day-a-week patient in analysis—an analysand it is called. How did that experience compare with receiving a liberal arts education?

MONTÁS: In my experience, psychoanalysis is like a liberal education carried out through different means. It takes the self as an object of investigation, respecting it as mysterious, not as a given but as an object of examination. In my own life, it was a way of stitching together aspects of my experience and my psyche that were pretty disconnected from each other: my experiences as a child in the Dominican Republic, which was all in Spanish; as an immigrant; as an Ivy League student, a poor Ivy League student; various relationships with intimates from different worlds.

Psychoanalysis was a systematic, methodical way of bringing some of the intellectual tools I had developed in the classroom into a close investigation of my own life and my own being in the world. You do it in psychoanalysis with a particular set of tools and with a particular kind of methodology that developed in the context of Freudian psychoanalysis, so it certainly has its own peculiarity, but it seems perfectly consistent with the project of liberal education.

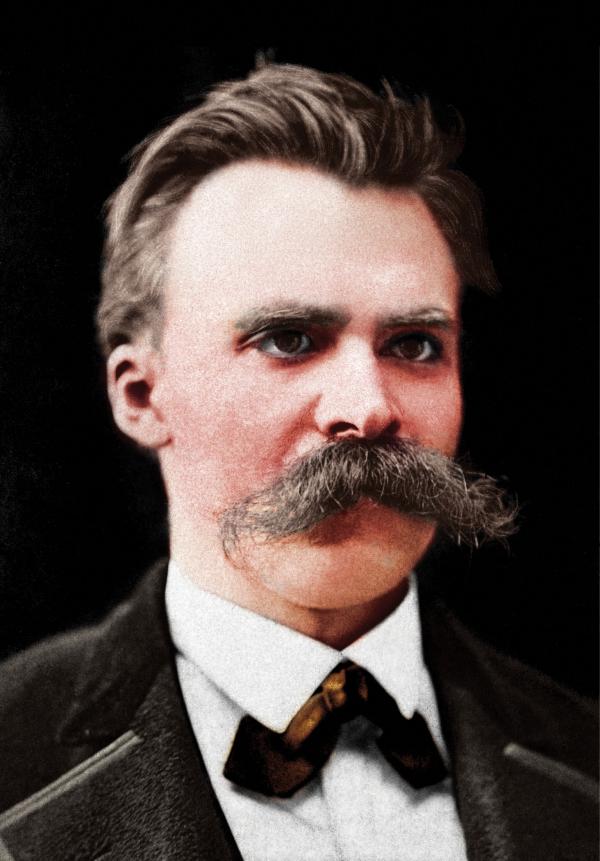

HUMANITIES: If there were a fifth thinker to put on the movie poster of your book, I would say it should be Friedrich Nietzsche. I wonder if you can walk us through how he comes into the discussion and why he is important to your analysis of what is commonly called the crisis in the humanities.

MONTÁS: Nietzsche has been a decisive influence on the intellectual framing of contemporary humanistic thought, particularly in the academy. One quote that comes to mind from him is “I am no man. I am dynamite.” He’s right about that.

Nietzsche’s destructive capacity, by which I mean his capacity to unsettle and explode conceptual frameworks, systems of belief, and ways of understanding the world, is really unsurpassed.

Nietzsche and his intellectual descendants, many of whom today we associate with postmodernism, deconstructionism, and critical theory, introduced a set of questions and a way of looking at the history of thought, the history of morality, and the history of social norms that erases or brings into question their metaphysical foundations. Notions like truth or virtue, good and evil and guilt, all come to be seen as tools for the exercise of power. Nietzsche is interested not so much in what truth is, but in what ways truth has developed and been deployed. What is the use of the notion of truth? To what uses has the notion of truth been put?

Nietzsche initiates an intellectual tradition that undermines concepts that are at the basis of a liberal education. A liberal education is concerned with human development, with human virtue, and with our human capacity to organize our lives according to a conception of the good. That presumes the human good is something that is rationally investigatable, and it also presumes that the investigation aims at truth and that truth is, to some degree, knowable. But if all of these notions are undermined and reduced to exercises of power, then you lose the grounding for a liberal education.

I addressed Nietzsche because it seems to me that at the bottom of much of the epistemological crisis of the humanities is this corrosive skepticism that comes into the conversation through Nietzsche. So, to try to recuperate the liberal arts, we need to address that directly, meaning the challenge that Nietzsche and postmodernism pose to us. And I tried to do that in the book.

HUMANITIES: Is this a way of saying that our humanities professors today are all Nietzscheans and that they reject the stability of the categories that underlie the Western tradition?

MONTÁS: Yes, except that I would not say all humanities professors. But this orientation is the dominant intellectual framing in the humanities. There are exceptions. Also, it’s contested and debated, but it is the dominant paradigm.

HUMANITIES: Let’s switch gears here to another of the modern thinkers that you discuss, who to me was a kind of revelation because I’ve never read him. Gandhi speaks of truth with a capital T. Truth is reality and God writ large. I’m not saying it’s crystal or obvious, but the truth is there and it’s real in a way that is very different from the shifting sands of perspectives that you find in Nietzsche and his descendants. First, how did Gandhi come into the core curriculum at Columbia and how do students react to Gandhi?

MONTÁS: I love that Gandhi appears in the Columbia core curriculum at the end of the second-year course in philosophy and ethics and social thought. Gandhi was incorporated into the curriculum in 2012. I was director of the core at that time and myself and a handful of other instructors had begun to teach Gandhi using the small degree of latitude that each instructor has to introduce his or her own material. So a bunch of us had begun to teach Gandhi.

You used the word “revelation.” It was something like that for many of us and our students. It worked extremely well in the classroom. It illuminated the whole syllabus in surprising ways and proved really important for the students. For one thing, it recuperated the notion of truth. It brought back into currency the possibility of a moral universe, of a universe that has some kind of moral coherence and that sticks together along something other than simply the raw exercise of power. In the humanities and the human sciences, power, or rather discourse as a tool for power, is as close to a bottom line as you get. Gandhi gives us a way to bring back into the discussion notions like truth, God, ethics, and nonviolence.

Yet Gandhi is no humanist. There are some basic assumptions in the Western philosophical tradition that Gandhi challenges, things like the supreme value of human life. Gandhi does not accept the supreme value of a human life. For him the value of human life is not superior to the value of animal life. Gandhi questions another given in the traditional political thought of the West, which is the right of self-defense. In the Western tradition, violence can be used legitimately to defend one’s own life and Gandhi rejects that notion.

Gandhi thinks there is no morally legitimate use of violence, period. It may be that you don’t have the kind of spiritual fortitude to accept suffering and accept being the victim of violence without retaliating, but that is a kind of moral failing, according to Gandhi. That does not, he says, make the violence legitimate. It only means that you have failed to attain the highest standard, you have failed to obtain the spiritual fortitude to follow the highest ethical path. Gandhi gives us a way of recuperating a morally coherent universe while introducing questions and perceptions that students find really illuminating and groundbreaking.

HUMANITIES: Gandhi must also be useful in giving you a bridge from some of these other traditions back to American political tradition in Martin Luther King Jr. Is that how you use him?

MONTÁS: It certainly comes up when you’re teaching Gandhi, both the influence that he had on the American civil rights movement and the influence that some American thinkers, specifically Henry David Thoreau, had on Gandhi. And there are other Western thinkers, Tolstoy, Ruskin, and Christianity generally that had a big influence on Gandhi. In turn, of course, Gandhi influences the civil rights movement. In my American studies courses, where I do teach Martin Luther King, all of those students have read Gandhi in their core classes, so the connection is there to be exploited.

HUMANITIES: What’s next for you? Do you have another book project in mind?

MONTÁS: I’m not sure. I haven’t settled on my next book project. I’m taking a breather. I’ve been on leave. I have a baby, who is now two and a half months old. I’m splitting my time between promoting the book and caring for the baby. I’m looking forward to getting back to the classroom in the spring. One possibility for my next book is to write about American issues. I’m an Americanist by training and I teach American political thought, so I am thinking of a book that looks at American political thought and American national identity.

Whatever I write is going to be, like Rescuing Socrates, very personal. Part of the reason I study America is to understand my own place in it. How is it that somebody like me can be an American citizen and can be a participant in the American political and cultural project?

I want to think about how a life like my own is made possible by the idea of America. What kind country is it in which someone like me can become American?