Novelist, essayist, and Christian thinker C. S. Lewis died on November 22, 1963, the same day President John F. Kennedy and writer Aldous Huxley died.

Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas, which overshadowed the passing of both Huxley and Lewis, broke open the 1960s. Along with the subsequent assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., as well as the deepening quagmire of war in Vietnam, that tragic day in Dallas defined a decade of declining confidence in traditional institutions.

Huxley, whose signature novel, Brave New World, questioned the conformity of consumerism and the power of the state, seemed to anticipate the rise of the counterculture for which the 1960s are best known.

Lewis was also deeply alert to the fallibilities of contemporary society, which strengthened his conviction that humanity needed to connect with a higher power to reach its true promise. In a radically changing world, his insistence on the centrality of orthodox Christian faith as a force for good struck many as a distinctly old-fashioned proposition.

More than half a century after his death, though, Lewis still often seems, to millions of devoted readers, freshly contemporary. His following includes Christians, as well as those of other faiths or no strongly declared faith at all. A core of devout readers finds his Christian apologetics persuasive. Lewis’s fiction, especially The Chronicles of Narnia, a series of children’s books, draws secular fans, too, and his essays and memoirs are appealing to many non-Christians. What resonates in those first-person writings is the humility of a man struggling, right there on the page, to face big questions and figure it all out.

The only problem is where to begin. Lewis wrote dozens of books, a potentially confusing maze for a newcomer who wants to get a sense of his work. Maybe the best places for a novice to start are Surprised by Joy, Lewis’s 1955 memoir, and A Grief Observed, his slender 1961 account of his bereavement for his wife, Joy Davidman, who died in 1960 after a painful struggle with cancer.

The subtitle of Surprised by Joy is The Shape of My Early Life, which signals Lewis’s self-deprecating sensibility. Notice that he doesn’t call this account the story of his life or the record of his existence. For all his wide learning—this is a man, after all, who taught literature at both Oxford and Cambridge universities—Lewis had a keen sense of how limited we are in seeing ourselves clearly. The narrative “shape” that he serves up, while admittedly impressionistic, doesn’t aspire to be a comprehensive chronicle.

Lewis, with typical humility, calls his book “suffocatingly subjective,” but that’s ultimately what makes it so readable. He was a child of the Edwardian age, an era known for its formal reserve and stiff upper lip. Despite its origins, the deeply personal tone of Surprised by Joy seems to anticipate the more intimate relationship that modern memoirists have with their readers. Surprised by Joy is proof that Lewis, for all his defense of tradition and orthodoxy, was something of a revolutionary.

Though the book covers only the author’s early years, key biographical points emerge. Clive Staples Lewis was born in 1898 in Belfast, Ireland. His father was a solicitor, his mother a clergyman’s daughter. Lewis’s paternal ancestry was Welsh, and his mother’s bloodline, as he put it, “went back to a Norman knight whose bones lie at Battle Abbey.”

Lewis’s father, he tells readers, “belonged to the first generation of his family that reached professional station.” The Lewises were middle class, though close enough to their lowlier origins that nothing was taken for granted. One of the running gags in Surprised by Joy is a worry by Lewis’s father, which we sense is overblown, that the clan is headed to the poorhouse.

Lewis lived in a house that, for all its ostensibly bourgeois security, seemed shadowed by the thought that good luck could quickly change. That prospect became vividly real when Lewis’s mother died while he was still a young boy. These days, bookstore shelves swell with memoirs about childhood struggles. This wasn’t the case when Lewis’s unblinking description of his mother’s death from cancer appeared in 1955. He recalls being led to her room for a deathbed viewing:

There was nothing that a grown-up would call disfigurement—except for that total disfigurement which is death itself. Grief was overwhelmed in terror. To this day, I do not know what they mean when they call dead bodies beautiful. The ugliest man alive is an angel of beauty compared with the loveliest of the dead.

As Lewis tells it, his father never recovered from the loss. Distanced from his surviving parent, the young Lewis became more bonded to his only sibling, his older brother, Warren. “We drew daily closer together . . . —two frightened urchins huddled for warmth in a bleak world,” Lewis writes.

That us-against-the-world perspective would pervade Lewis’s life and work. He fell in love with mythic tales about a resolute few against the multitude of the powerful. It’s a key plot element in his Narnia stories and is arguably central to his theology. Lewis not only tolerated but embraced, one gathers, his role as an observant Christian within a community of skeptics.

Aside from the companionship of his brother, Lewis sought connection in books. Reading was rapture for him. It surfaces as a theme throughout his personal writings—so much so that in 2019, editors David C. Downing and Michael G. Maudlin published The Reading Life, a survey of Lewis’s reflections on the ecstasies of the written word. “At the age of ten, Lewis started reading Milton’s Paradise Lost,” they note in their introduction. “By age eleven, he began his lifelong habit of seasoning his letters with quotations from the Bible and Shakespeare. In his mid teens, Lewis was reading classic and contemporary works in Greek, Latin, French, German, and Italian.”

Lewis didn’t have to go far to find books. Both of his parents, as well as his brother, were voracious readers. His house groaned with volumes. Here’s Lewis:

My father bought all the books he read and never got rid of any of them. There were books in the study, books in the drawing-room, books in the cloakroom, books (two deep) in the great bookcase on the landing, books in a bedroom, books piled high as my shoulder in the cistern attic, books of all kinds reflecting every transient stage of my parents’ interests, books readable and unreadable, books suitable for a child and books most emphatically not. Nothing was forbidden me.

When he left home to study in England, Lewis depended on mail orders to keep him supplied with reading. He counted it as a great piece of luck that he had come of age as cheaply produced classics were becoming widely available. Lewis felt giddy at the chance to read the new arrivals:

No days . . . were happier than those on which the afternoon post brought me a neat little parcel in dark grey paper. Milton, Spenser, Malory, The High History of the Holy Grail, the Laxdale Saga, Ronsard, Chénier, Voltaire, Beowulf, and Gawain and the Green Knight . . . came volume by volume into my hands.

Lewis seemed proud of the fact that he could read anywhere, noting that he “first read Browning’s Paracelsus by a candle which went out and had to be relit whenever a big battery fired in a pit below me, which I think it did every four minutes that night.”

That memorable literary encounter unfolded as Lewis served in World War I. By that point, he’d abandoned the religious faith of his childhood. But, while convalescing from a fever for three weeks in a military hospital, Lewis read some essays by the Christian spiritual writer G. K. Chesterton that nudged him to rethink his choices. “In reading Chesterton . . . I did not know what I was letting myself in for,” Lewis recalled. “A young man who wishes to remain a sound Atheist cannot be too careful of his reading.”

After the war, Lewis resumed his academic life at Oxford, where he read and thought more deeply about the question of God’s existence, a period of reflection that ultimately led him back to his Christian faith. He had felt joy while connecting with nature and literature, but the chief conclusion of Surprised by Joy is that such jolts of transcendence have ultimate meaning only if they point to some larger source. For Lewis, that wellspring was God.

His subsequent career had obvious parallels with Chesterton (1874–1936), the British man of letters who had helped turn Lewis back to Christian belief. As with Chesterton, who authored lively theological works such as The Everlasting Man, along with the celebrated whodunits of the Father Brown mystery series, Lewis alternated between writing Christian commentaries and popular fiction.

Yet such comparisons go only so far. While Chesterton can seem pontifical in his pronouncements, expressing a certitude that treads the line with glibness, Lewis at his best displays a winning vulnerability in his autobiographical writings.

The more obvious role model for Lewis was Samuel Johnson, the eighteenth-century poet, essayist, and lexicographer who also did his share of writings about Christian faith. Lewis listed James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson as “one of the ten books that most influenced his thought and vocational attitude,” scholar Colin Duriez notes.

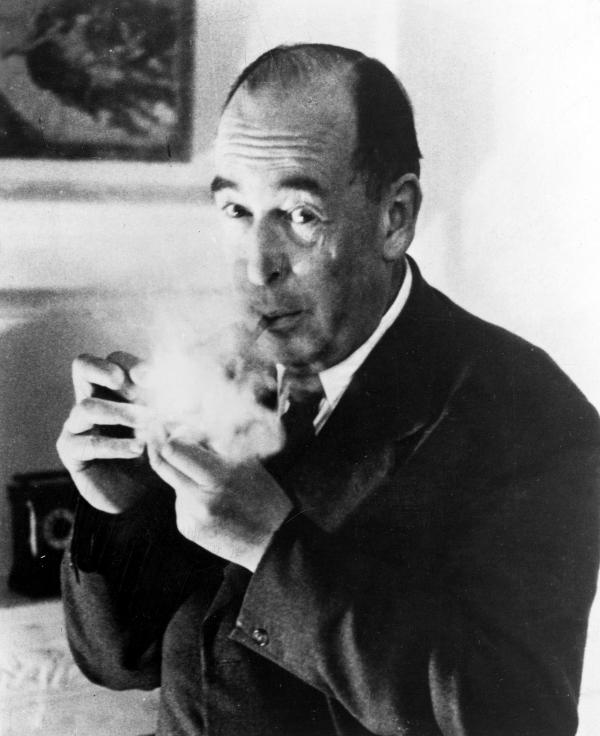

Johnson’s colloquies in London coffeehouses have their natural heir in the Inklings, an assortment of Oxford writers that included Lewis and The Lord of the Rings author, J.R.R. Tolkien. The group often met at a local pub, a setting that suited Lewis’s bawdy side. “He was loud,” biographer A. N. Wilson writes of Lewis, “and he could be coarse. . . . He was a heavy smoker—sixty cigarettes a day between pipes—and he liked to drink deep, roaring out his unfashionable views in Oxford bars. . . . But I also learnt that he was a kind and patient teacher, a loyal friend, a magnificently astute and intelligent conversationalist.”

As Wilson also points out, Lewis “liked what he called ‘man's talk,’ and he was frequently contemptuous in his remarks about the opposite sex.” Nevertheless, he demonstrated great tenderness and generosity with women. Lewis helped financially support the struggling American poet Mary Willis Shelburne, though they never met in person. His correspondence with her, collected in Letters to an American Lady, points to his abiding respect for her intellect. He was also a big fan of Jane Austen. “I’ve been reading Pride and Prejudice on and off all my life,” he noted, “and it doesn’t wear out a bit.”

Lewis’s views on other social matters are equally complex. In Surprised by Joy, Lewis dismisses Hinduism in a handful of lines, suggesting a cultural condescension that seems particularly off-key to modern ears. Lewis’s perspectives on other faiths have raised eyebrows, too.

“The principal bad guys, the Calormenes, are unmistakable Muslim stand-ins,” author Gregg Easterbrook wrote in a 2001 Atlantic article about characters in Lewis’s Narnia series. But Easterbrook also found much to like in Lewis’s fictional tales. The presence of Emeth, an admirable Calormene, suggests that virtue isn’t exclusive to just one faith. “In Narnia, after all, heaven has an open-door policy. . . . This seems an up-to-date message—and a reason,” writes Easterbrook, “the Narnia books should stand exactly as they are.”

Lewis was ultimately more complicated than the popular image of him as a saint, which is perhaps the biggest reason biographers never seem to tire of him. Along with Wilson’s C. S. Lewis, readers can also delve into Alister McGrath’s C. S. Lewis: A Life, Alan Jacobs’s The Narnian, and Duriez’s The C. S. Lewis Chronicles.

To read Wilson’s depiction of Lewis’s world is to be reminded that it was mostly male, a notable exception being Joy Davidman, the American writer he married in 1956. She was then a divorcée with two small boys, and Lewis was a confirmed bachelor.

Their love—and Lewis’s subsequent agony after Joy’s death—are the subject of A Grief Observed, his most personal book.

The story, dramatized in two movie adaptations and a stage play called Shadowlands, is compelling because it involves a man whose faith, so eloquently expressed in books, is tested in the crucible of tragedy. But it would be a mistake to think of Lewis as a sheltered Oxford don before he met Davidson. His childhood had been messy at times, and his wartime experiences were another trial.

What resonates in A Grief Observed is how piercingly candid it seems. Surprised by Joy, though often strikingly revealing, especially for its era, was still touched at times by a resigned reticence. Like so many men of his day who attended British boarding schools, Lewis endured bullying, privations, and abuse, hardships that are generally dispatched in Surprised by Joy with a shrug. He’s equally matter-of-fact about being wounded in combat and losing comrades in battle during his military service.

“The war itself,” he writes with an apparent sigh, “has been so often described by those who saw more of it than I that I shall here say little about it.” Tellingly, in a subsequent chapter, Lewis makes only a passing reference to his father’s death.

So, nothing quite prepares readers for the emotionally raw tenor of A Grief Observed. Its memorable opening lines circle the mind like a raven: “No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear. I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid. The same fluttering in the stomach, the same restlessness, the yawning. I keep on swallowing.”

Perhaps part of the reason that Lewis felt at liberty to be so candid is that A Grief Observed was originally published under a pseudonym, N. W. Clerk. “Lewis, anxious not to cause his friends any embarrassment, decided to conceal his authorship,” notes McGrath.

Lewis’s sentiment was typical of the times. When A Grief Observed appeared in the 1960s, few people publicly discussed bereavement. Due in no small measure to Lewis, the culture of grief has changed. Memoirs of bereavement, such as Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking and Helen Macdonald’s H Is for Hawk, abound. Lewis, a pioneer of the genre, paved the way. “What many of us discover in this outpouring of anguish is that we know exactly what he is talking about,” Lewis’s stepson, Douglas H. Gresham, has written of A Grief Observed. “Those of us who have walked this same path, or are walking it as we read this book, find that we are not, after all, as alone as we thought.”

Author Madeleine L’Engle revisited the book as a new widow. “Reading A Grief Observed during my own grief made me understand that each experience of grief is unique,” wrote L’Engle, who died in 2007.

An abiding paradox of A Grief Observed, so often sent as a gift to those recently touched by loss, is that it’s a sad book tinged with pleasure—the consonance that comes from seeing a sentiment perfectly put, a sentence spun onto the page with seemingly effortless grace.

It’s the kind of magic that Lewis sought as a reader himself. “We want to see with other eyes, to imagine with other imaginations, to feel with other hearts, as well as with our own,” he wrote of his own adventure in books.

Of his old idol Chesterton’s prose, Lewis recalled that “I did not need to accept what Chesterton said in order to enjoy it.”

The same is often true of Lewis, who continues to attract readers beyond the Christian faith. Ultimately, warts and all, what he offers is a universal story, the record of a pilgrim testing belief against life.

“What I like about experience,” he told readers, “is that it is such an honest thing.

. . . You may have deceived yourself, but experience is not trying to deceive you. The universe rings true wherever you fairly test it.”