In April 1968, the British photographer Don McCullin made his first trip to Biafra, the newly independent republic that had broken away from Nigeria the year before. The celebrated war photographer had spent years covering Congo, then Vietnam, photographing terrible violence and raw terror. This time, McCullin, accompanied by the French photographer Gilles Caron, joined a poorly outfitted Biafran unit that attempted to make an incursion into the Nigerian-controlled area of Biafra. The two men saw devastating injuries, a problematic captain, a woman burned alive in a car, and dozens of young Biafran soldiers who were afraid and hopelessly outgunned.

McCullin’s photographs appeared in the London Sunday Times Magazine in June: a spread of color images of injured men, homemade rockets, and barefoot Biafran soldiers. “Even the Vietcong don’t operate barefoot,” McCullin commented. The accompanying story was written by famed Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe, who identified as Biafran and described the Biafran cause as an existential one. “The strength of Biafra lies in the fact that it is fighting a people’s war. The entire population is in it.” In reality, though, the war was not going well for the Biafran side. McCullin returned many times to Biafra, but already, in that first visit, he was beginning to doubt not only the viability but also the justice of the Biafran cause.

When McCullin began chronicling the Nigeria-Biafra war, most people in Europe and the United States had heard little about it. The war had begun a year earlier, when the largely Igbo population of the Eastern Region began fighting for independence, far outgunned by the Nigerian federal government. Most people expected the war to be over quickly. It wasn’t. And by the middle of 1968, McCullin had joined a transnational coterie of photographers, humanitarians, and activists who struggled to bring news of the conflict, and the ensuing starvation in Biafra, to the outside world.

During the two-and-a-half-year war, as many as a million civilians died. Many of those deaths were from starvation. Both sides used hunger as a weapon. For the Nigerian military government, the goal was to starve a rebellious population of both weapons and sustenance. For the Biafran leaders, the undeniable suffering of their population became their most effective tool in gaining external support.

Photographers and reporters from the rest of the world were central to Biafra’s strategy. Their images and stories reached homes all over the globe, and people across Africa, Europe, and the United States were deeply moved. In those photos, the suffering of children was paramount. Images of starving children were not new in the late 1960s, but in Biafra, the starvation came to be linked to political questions about global power and politics. At the same moment that the war in Vietnam was becoming America’s first television war, the Nigeria-Biafra conflict was different; it was, as researcher David Campbell writes, “the last war in which newspapers scooped television, and black and white photographs played a major role.” Americans, seeing images of starving children in Life or Newsweek, were angry that more was not being done. In late 1968, as the war on the ground turned against the Biafrans, an alliance of citizen groups—European and American, secular and religious—began flying dangerous nighttime missions into Biafra in defiance of a Nigerian blockade, delivering food and medicine. The work of reporters and photographers galvanized citizen activism, which pushed for more aggressive responses by international humanitarian groups.

With both media and ordinary activists joining the fray, Biafra was the beginning of the modern politics of humanitarianism. Yet the intertwined history of photography and humanitarianism left an ambiguous legacy. Some photographers, including McCullin, eventually began to question the impact of their work: They had moved hearts and minds, but to what end? For some humanitarians, too, Biafra became a case study in how aid can become politicized, implicating “neutral” actors in one side of a conflict, perhaps even prolonging the war and making things worse for the people they aimed to help. Humanitarianism is often imagined as straightforward: simply feeding the hungry and healing the injured in a situation of emergency. Biafra taught a more complex lesson.

***

Until recently, the Nigeria-Biafra war was rarely analyzed by either scholars or artists. “The world was silent when we died,” wrote Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in her extraordinary war novel, Half of a Yellow Sun. But the world was less silent during the war than it became afterward. For two years, it was a transnational phenomenon. And then, once the war ended in 1970, Biafra became relegated to little more than a footnote in the history of decolonization or, perhaps, a half-mythical object lesson for humanitarians. Within Nigeria, it became something else: the third rail of national politics, not forgotten so much as unspeakable.

When the Nigeria-Biafra war began in 1967, it was both shocking and entirely predictable. The early 1960s had been a rather joyous rollout of decolonization around the world; the UN declared 1960 the Year of Africa, as 17 nations became independent. And Nigeria was the crown jewel of postcolonial Africa: large, populous, prosperous. In the mid-1960s, Nigeria was an emerging oil producer, with a rapidly growing class of wealthy entrepreneurs. And it was home to a major literary scene, boasting renowned writers Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Buchi Emecheta among others, as well as a thriving music hub (where African Highlife competed with young jazz and rock bands), and a world-class community of painters. For many observers in the United States and Europe, Nigeria represented the possibilities of liberated Africa.

The struggle for decolonization was also accompanied by violence. There were wars of liberation that quickly became deadly civil wars—in Vietnam and Congo, among others. Nigeria was not immune. After all, the country was something of a British invention from the beginning: Created in 1914 by the British governor general, who combined two distinct colonial protectorates and named them Nigeria. Culturally, Nigeria was generally divided into three regions. The Hausa and Fulani people were concentrated in the north, and were almost entirely Muslim; in the southwest, where much of the population was Yoruba, religious affiliation was split between Christians, Muslims, and followers of traditional African religions. The east, the largely Igbo area that would eventually become Biafra, was the most Christianized area of the country, where a majority of the population were Roman Catholics. Within these regions were a wide range of ethnicities and perhaps 200 distinct languages. As Adichie put it in the London Review of Books, “It is debatable whether, at independence, Nigeria was a nation at all.”

Indeed, there were deep divides about the relative political power of the different regions, as well as divisions over how to distribute wealth from oil found in the Niger Delta. The proximate cause of the war was a military coup in early 1966, led largely by Igbo officers from the Eastern Region, followed by a counter-coup a few months later. Both disputes were about divisions of power in the civilian government as well as sectarian tensions in the military. In the fall of 1966, there were a series of massacres against Igbo people living in the north. Thousands of people were slaughtered; many thousands more Igbo fled back to families and homes in the Eastern Region.

In May 1967, with tensions increasing on all sides, Colonel Odumegwu Emeka Ojukwu announced the secession of the newly declared state of Biafra in the Eastern Region. The following month, the Federal Military Government of Nigeria initiated a complete embargo on the shipping of goods to and from Biafra. The immediate response of the international community was muted, while the Organization of African Unity supported Nigeria in its argument that the conflict over Biafra was an internal one. Most heads of African states were not interested in encouraging the idea that ethnically distinct areas had the right to secede. As the war progressed and the humanitarian crisis grew, a few key African leaders would recognize the state of Biafra. For much of the war, however, official African opinion was clearly on Nigeria’s side.

As the former colonial power, the British strongly supported “one Nigeria,” and supplied weapons to the Nigerian army through the course of the war. The Soviets also backed Nigeria, although more quietly. Of the major world powers, France and Israel were strongly supportive of Biafra (yet neither officially recognized it as a state). The U.S. State Department claimed to be neutral, but its position called for a negotiated settlement that would not include independence for Biafra. At the height of the Vietnam War, there was initial support for President Lyndon B. Johnson’s decision to remain relatively uninvolved, essentially shoring up the positions already articulated by the British and the OAU. This made the Nigeria-Biafra war one of the very few Third World conflicts that did not divide the United States and the USSR along Cold War lines. Although the State Department would eventually fund some of the relief efforts carried out by churches, critics saw the official U.S. position as “timid,” “nebulous,” and “lethargic”—an almost studied refusal to recognize Biafran claims, or even Biafran suffering.

In March 1968, however, the conflict that the African American magazine Jet had called the “war between Blacks that no one cares about” won broader public attention as the blockade massively increased human suffering in Biafra. Although the Red Cross was allowed to fly in some supplies, there was an increasingly dire lack of food, medicine, and other necessities. Then the British (and to some degree, U.S.) press began to report that the Nigerians had begun to bomb civilian targets. An article in the Irish Times carried the headline “War in the Air: Defenseless Civilians are Massacred by Nigerian Jets.” In the New York Times, Lloyd Garrison wrote a long, passionate piece that described the situation for civilians: the bombings, including attacks on schools; the lack of medical supplies; the conviction of the Biafrans that they were being targeted for genocide.

In the summer of 1968, a wide swath of journalists began to report on the food crisis in Biafra. The British magazine the Sun published dramatic and emotionally powerful photos of starving children; Germany’s Der Spiegel ran a cover story “Biafra: Death Sentence for a People.” In the United States, the New York Times, Washington Post, Time, Newsweek, and Chicago Defender, one of the nation’s most important African American newspapers, all published detailed accounts of the dramatic rise of kwashiorkor, a life-threatening protein deficiency in children in Biafra (and in adults, but children tended to be affected first). This was the kind of hunger that led to skeletal bodies with big bellies, which would soon become the paradigmatic image of the Biafra war. There were reports of measles and tuberculosis ravaging weakened populations, children eating insects and rodents, dead bodies on the street. One headline in the Chicago Defender put it bluntly: “People Dying Like Flies in Steamy Biafra.”

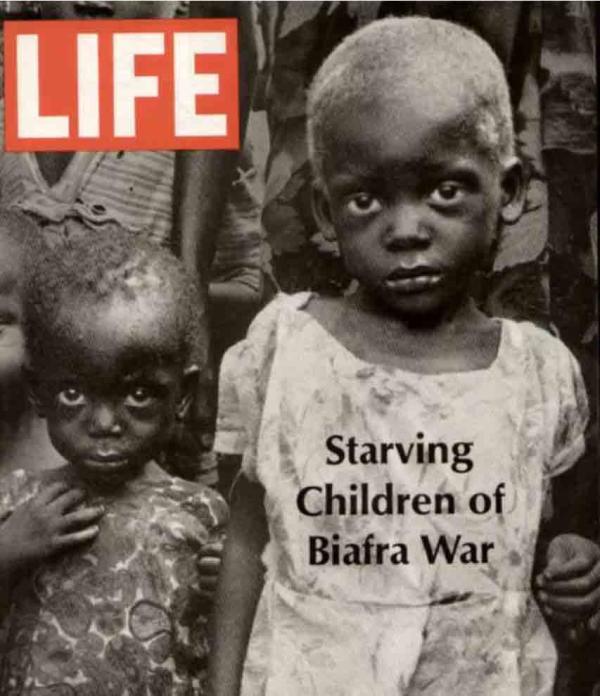

Life magazine’s cover story in July of 1968 sent a shock through the United States. Ten pages of dramatic photos mostly focused on the civilians who were trying to survive in the devastated and shrinking territory of Biafra. The cover photo was two beautiful young children, with large eyes and heads, staring straight into the camera. Inside, photos of dead bodies and mourning mothers crowded against more images of children, emaciated and crying. Other photos in the essay were in color, but those of the children were in black and white. Reporter Michael Mok described walking through a village where a little girl of about five years old held a wailing baby. “There were other children in the huts, dead or dying,” Mok wrote. “I don’t want to remember their wasted bodies.”

Susan Sontag has famously argued that photography has the power to move people, but also the power to inure them to what they see. “To suffer is one thing,” Sontag wrote in 1977. “[A]nother thing is living with the photographed images of suffering, which does not necessarily strengthen conscience and the ability to be compassionate. It can also corrupt them. Once one has seen such images, one has started down the road of seeing more—and more. Images transfix. Images anesthetize.” In the case of Biafra, the images did move people, did elicit compassion and action. But the reaction was not inherent in the photos themselves. Photographs help shape understandings, cultivate feelings, encourage action. But exactly what feelings, what actions are never dictated by the images themselves. Photographs are always captioned; if not literally, then by history itself, by the context in which they are viewed. And the children of Biafra arrived in the United States and Europe in the summer of 1968.

In April, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. In June, Robert F. Kennedy was shot and killed, and, in August, young people protested outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago against the war in Vietnam. In those same months, a very different group of activists began to coalesce around Biafra. Their motives varied, but they tended to be older than the anti-Vietnam War protestors, more mainstream politically, and often more religious. Over the next 18 months, scores of ad hoc groups would form across the United States to advocate for humanitarian aid to Biafra: the American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive; the Food for Biafra Committee; Americans for Biafran Relief; the Bay Area Committee to Save Biafran Children; the Kansas City Committee for Biafra-Nigeria Relief; and the Joint Afro Committee on Biafra, among others. They held candlelight vigils, lobbied Congress to get U.S. aid directly to Biafra, and raised money. Most claimed their concerns were apolitical, focused only on humanitarianism and basic human needs. They gestured back to the forms of humanitarianism Americans would have been most familiar with: large organizations that often worked closely with the U.S. government, led from the top. CARE, Caritas, or the Red Cross solicited money from donors, offering them a chance to be thankful for their own blessings by sharing with those “less fortunate.” They asked almost nothing else from their supporters.

The situation was more complex regarding Biafra. The American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive (ACKBA), for example, soon included local groups that organized candlelight marches and grassroots fundraisers, alongside nationally coordinated lobbying on Capitol Hill. That was different in itself. But eventually the leaders of ACKBA came to believe that nonpartisan aid was not enough: Biafrans could not be “kept alive” without a state of their own. The group demanded U.S. recognition for Biafra. ACKBA also linked the suffering in Biafra to the Holocaust and demanded a kind of reparations for the world’s failure to stop the concentration camps of World War II. In August 1968, ACKBA ran an ad in the New York-based Jewish Press that included a photo of a group of horribly emaciated children with the copy: “6 million. Dear God, not again.”

Also in the summer of 1968, the American Jewish Committee spearheaded the 21-member American Jewish Emergency Effort for Biafran Relief. (It would later change its name to include Nigeria as well as Biafra.) That organization raised $185,000 in its first year (about $1.5 million in 2023 dollars). The leader of the effort, Rabbi Marc Tannenbaum, worked closely with U.S. churches in funneling aid. Tannenbaum presented AJC’s humanitarian work as emerging even more strongly from the memory of the Holocaust. American Jews, he argued, would not reproduce “the silence of governments, universities, and church institutions, among others, who, by and large, were spectators to the Nazis’ ‘final solution of the Jewish problem’ in Europe. . . . ‘Thou shalt not stand idly by the blood of thy brother’ has become virtually the eleventh commandment in contemporary Judaism.” This was a long way from the benevolent paternalism of an earlier era. The fundraising for Biafra often did present the war’s victims as passive and pitiful but it emerged, first and foremost, from people who saw even their nonpartisan humanitarianism as a form of activism. More than 20 years after the end of World War II, and in the wake of deep divisions between radical activists on the one hand and the people President Richard M. Nixon would soon call the “silent majority,” on the other, there emerged a sense of middle-ground possibility: Moral witness could cross political divides.

In Europe, too, the diverse organizations who began to respond to the crisis in Biafra often agreed on little other than the need for something to be done. Most groups focused on raising funds for and/or delivering aid. Caritas, the Catholic relief organization, had been working since January 1968. By the summer, Oxfam and Save the Children were sending teams to Biafra. The Britain-Biafra Association published books and advertisements decrying what it described as Britain’s implication in the “genocide” in Biafra. In Ireland, activists formed Africa Concern, which raised one million Irish pounds and starting shipping aid directly. In France, policymakers were generally more sympathetic to Biafra than those in the United States or United Kingdom; France and Israel both sent weapons. It was also in France that citizen activists developed the dream of “sans-frontiérisme.” The official histories of Doctors without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières) locate its origins in the frustration of young French volunteers in Biafra, who felt that the large international organizations were not nimble or brave enough in the face of devastating crisis. Historians have more recently complicated that overly simple story, but there is no question that Biafra catapulted a range of disillusioned young activists into crafting new forms of muscular humanitarianism.

The conflict over how to get aid to Biafra was never apolitical, because starvation was a weapon for both sides. The deadlock between Gowon, the Nigerian president, and Ojukwu, the Biafran leader, centered on which side would control the route of food and medicine into Biafra. The Nigerian side refused to allow any aid flights that did not fly through Nigerian airspace—flights coming in from nearby islands directly into Biafra would be shot down. Instead, they proposed a land corridor that would allow supplies to come in through Nigerian territory, controlled and inspected by the Red Cross. Biafra’s Ojukwu was equally intransigent: He rejected the land corridor, insisting any food coming from Nigerian territory, even if internationally monitored, would probably be poisoned. The more likely reason was symbolic: An independent Biafra was simply refusing to be dependent on aid controlled by Nigeria.

But, as the media reports made clear, the question of how many people were dying also very quickly became a political question. News accounts at the time noted the question of numbers and the intractable logic of political calculation on each side. Almost all the reports acknowledged that Biafran numbers—claims that 3,000 a day were dying in the summer, as many as 6,000 by the fall—were exaggerated. When, in July 1968, Biafran officials announced that 3 percent of its population was dying of starvation each week, the Washington Post quoted “neutral observers” who declared the number “close to preposterous.”

What was clear is that the Biafrans understood that the images of starving children had become their most potent weapon in the battle for world opinion. Indeed, the Nigerians and British, and sometimes Americans, as well as a number of people in the media, accused the Biafrans of heightening the suffering of their own people for political gain, citing their failure to negotiate a land corridor for getting aid into the territory. Similarly, the Nigerians could have allowed relief to be flown in, but instead had threatened to shoot down any plane that did not come through Lagos. “The victims of this disaster,” one commentator fumed, “are insulted by the arithmetical propaganda from both sides in the Nigerian civil war.”

No less an organization than the World Council of Churches (WCC), one of the largest organizations in the world uniting various Christian denominations, was hamstrung by the question of how to respond to the war. There was no option to ignore it. In the summer of 1968, one of its five co-presidents was an Igbo who had formerly been governor of the Eastern Region of Nigeria. Francis Akanu Ibiam wanted Biafra on the WCC’s agenda. But the WCC was a global organization of churches, including many Nigerian ones. The contentious debate at the meeting ended with a tepid call to deliver food for the hungry.

Amidst all of this activity, what few people talked about was the fact that the volunteers, the medicine, and the cash were all arriving late to the game. The conflict had become a slow, devastating war of attrition, one that Biafra had no real chance of winning. But Biafra’s leaders refused to give up, convinced that the Federal Military Government would slaughter Biafrans en masse if it won. At the same time, it was clear that the food and medicine were going to Biafra’s fighters as well as its children. Sir Michael Aaronson, the former chief executive of Save the Children UK, began his career in Biafra. He recognized that perhaps the aid had actually prolonged the war, allowing Biafran fighters to continue long after the war was lost. But he also made a simple point: “Were we supposed to see the starvation, and walk away? We were not war strategists. We were humanitarians.”

By 1969, the situation in Biafra was horrific. Don McCullin returned that spring. This time, the bulk of his images were of starving civilians or badly injured decommissioned soldiers. There was a young woman staring at the camera with something like resignation, her starving child trying to get milk from her desiccated breasts. A man and two children in rags, one of whom would be dead within a week. It was on that trip that McCullin took “one of the most obscene photographs I’ve ever taken.” It was also his most famous photo: a closeup of a starving albino child—skeletal legs, his head seeming to totter on his emaciated frame, holding an empty can. “He was an albino boy,” McCullin remembered later, “and he was standing looking at me, barely managing to stand on his spindly legs . . . He was making me feel so ashamed.” McCullin acknowledged that his paper, the Sunday Times Magazine, was still strongly supportive of Biafra’s independence. His photographs appeared in an essay by Richard West, “The Accusing Face of Young Biafra,” which stated simply that “the extinction of Biafra would be a disaster for the whole of Black Africa.” But McCullin himself was no longer a partisan. He knew that the Biafran leadership was using people like him. And, while he knew his photography had some kind of message, he was no longer sure exactly what that message was—“except, perhaps, that I wanted to break the hearts and spirits of secure people.”

Biafra surrendered in January of 1970 and the two-and-a-half-year war came to an end. There were no mass killings by Nigerian forces, as many had feared. But the Eastern Region of Biafra was devastated, with perhaps as many as a million people dead. The Africanist scholar Alex de Waal called Biafra the “totem and taboo” of the modern humanitarian movement. The extraordinary response was proof of the capacity of nongovernmental organizations, who were able to mobilize public opinion to react quickly and effectively. Churches and secular groups alike responded to suffering and starvation with impressive resources and reserves of human commitment. They did not prevent famine, but they helped it from becoming far worse. And yet, the evaluation of some humanitarian organizations and some journalists was that, in hindsight, they were overly quick to react to the propaganda of the Biafran leadership, to overlook the diversion of food from civilian to military needs. Today, more than 53 years later, there are those who would revitalize the call for Biafran independence; others who see the cause as dead but the war’s injuries as still unhealed.

Nor for U.S. and European activists was the end of the war the end of the story. They had learned that supporting the needs of the hungry and the suffering could involve more than writing a check. In 1968, activists created a new form of civilian-led, media-driven humanitarianism that became a global force. They pressed for government action, responded to the fact of human suffering with political organizing, and insisted on intervention. The “new humanitarianism” still claimed to be politically neutral, but it insisted on the right to move wherever the need was, without regard for state boundaries. “Sans-Frontiérisme” was more than the name of one organization; it was a vision of humanitarian imperatives that trumped state politics. Compassion moved to center stage, quite literally. In the coming years, Oxfam would become a household name, and humanitarians would hold the Concert for Bangladesh, in 1971, and the largest televised event in history, the Live Aid concert for Ethiopia, in 1985. These performances were accompanied by a rising tide of citizen activism on all sorts of issues in the 1970s and 1980s, from the environment to feminism to nuclear war.

Photographs speak, but not for themselves. They are situated in, scripted by, and conscripted into particular contexts, specific historical moments. Activists emerge and fight, but not from nowhere. For humanitarian activists, the positions they struggle to hold are almost never as neutral, as “apolitical,” as either they or their critics might imagine. The transnational movement on behalf of Biafra was short-lived but powerful. It saved lives, no question. It also remade humanitarianism into something that captured the imagination and the passions of ordinary people, turning audiences into activists.