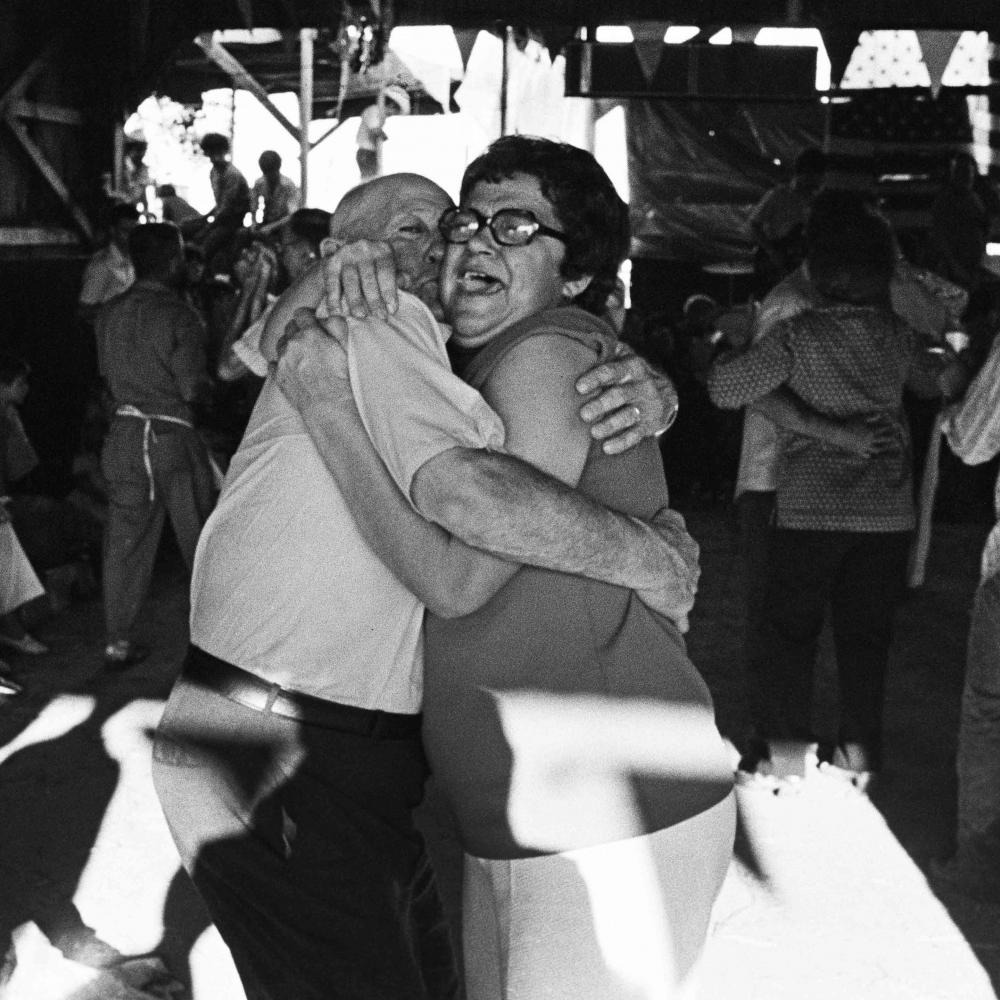

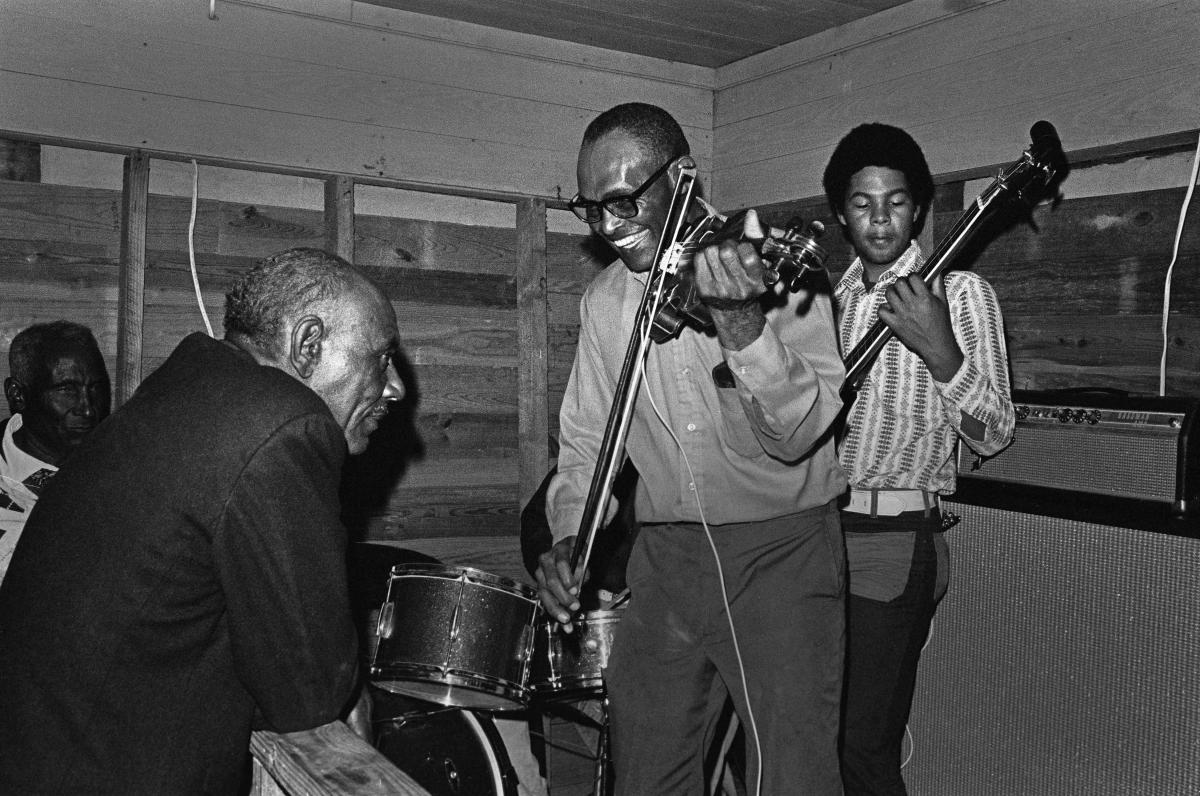

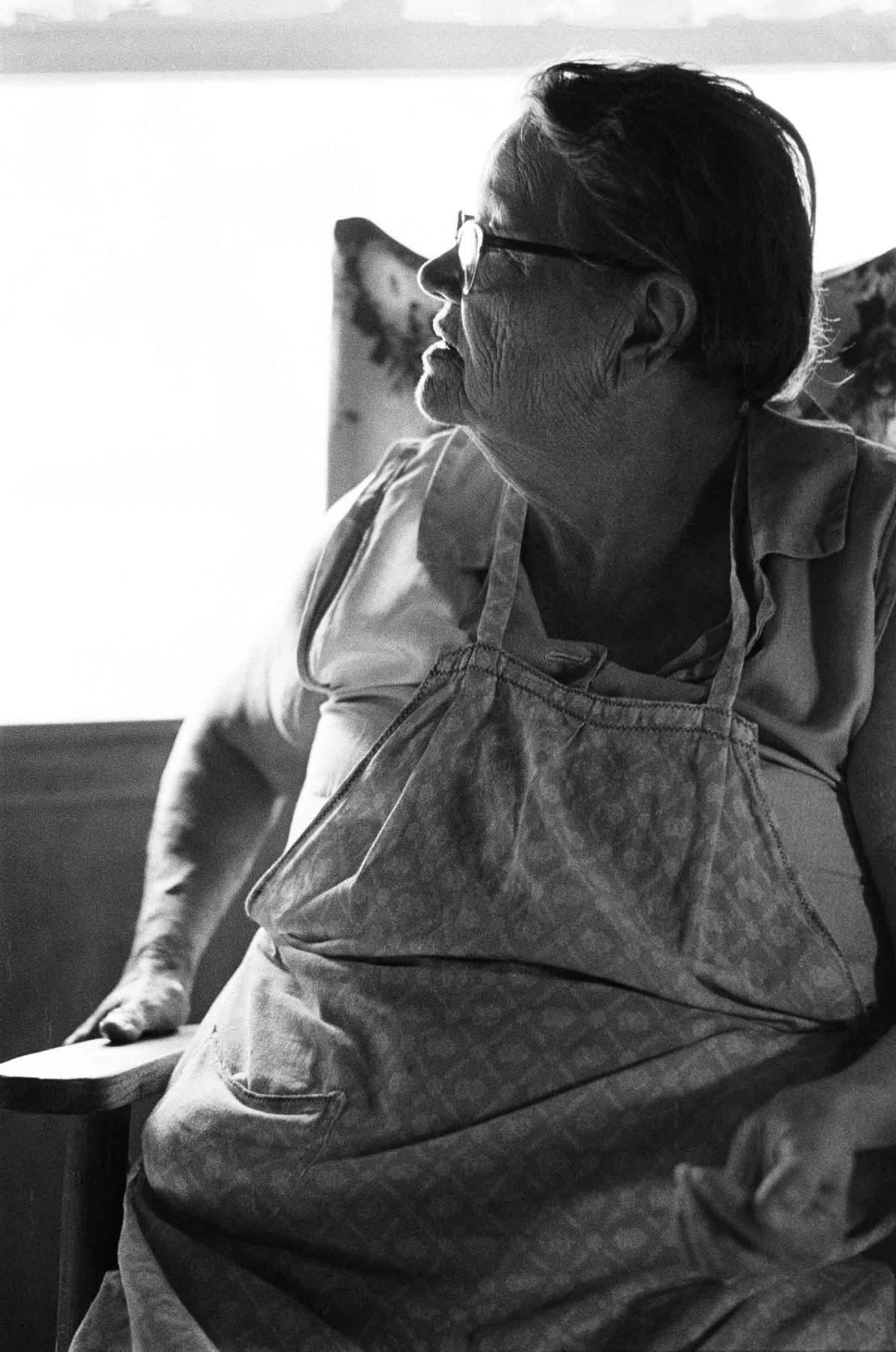

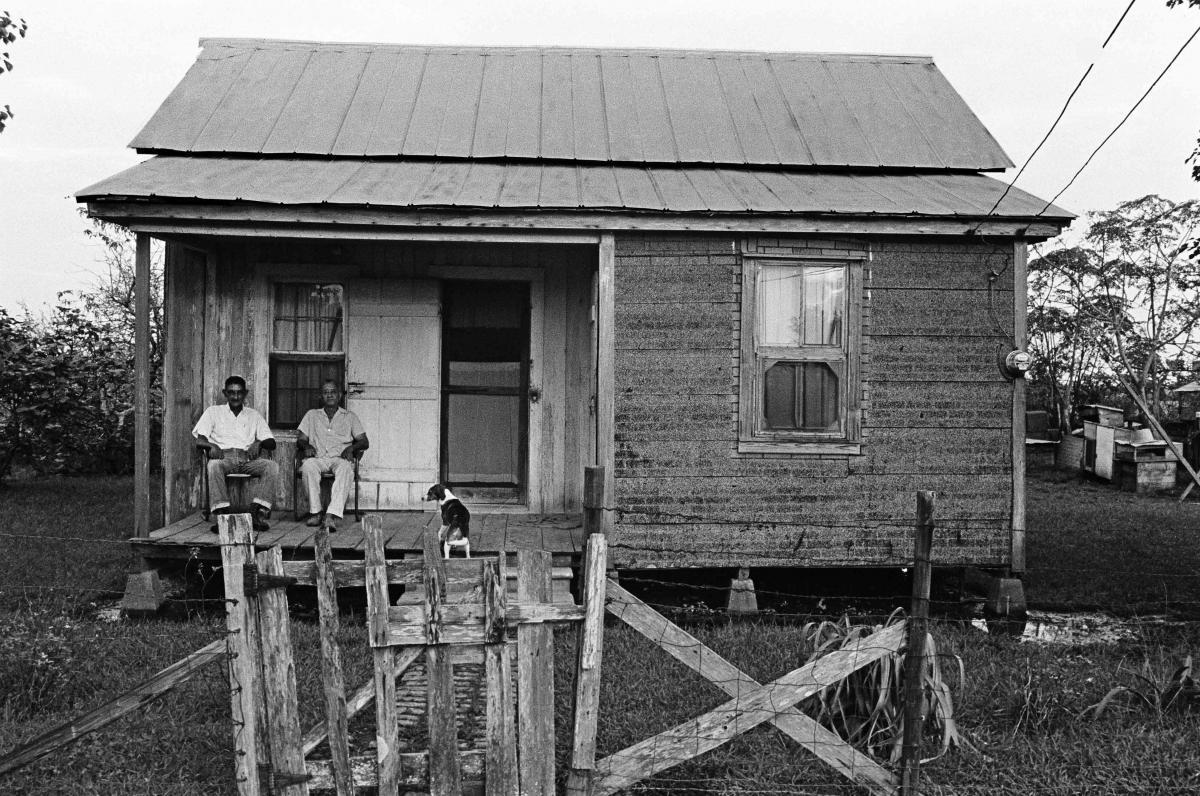

When they first heard performances of Cajun and zydeco music from south Louisiana, Ron Stanford and his future wife, Fay, were deeply moved by the experience. The suggestion, later, by Dewey Balfa, who had grown up surrounded by Cajun music and culture, that the Stanfords live in Louisiana someday was serendipitous. Balfa’s invitation gave the Stanfords an in, and his generosity, as Ron Stanford describes in the afterword to his photo album, Big French Dance, allowed Ron and Fay to live inexpensively in a home on a thousand-acre cattle and rice farm. The couple converted a smokehouse into a darkroom and, with help from an NEH grant, documented Cajun and zydeco music. The two years they spent photographing and interviewing musicians in their homes and in dance halls had an impact much later that neither the Stanfords nor the performers could imagine at the time. The music, recorded more than 45 years ago, can now serve as a time capsule, as can the photographs Ron Stanford rediscovered decades later. The Stanfords had seen and heard things strange and wonderful, and the images in the following photo essay capture their time in Louisiana in powerful, intimate ways that reveal how music defines black and white families in south Louisiana. They are also proof of the enduring power of NEH grants, which can transform the lives of both those who receive them and the communities celebrated by young people like Fay and Ron Stanford. This important partnership allowed the Stanfords to compile a landmark collection of photographs that beautifully captures the history of a people and their beloved music for future generations. —William R. Ferris

(William R. Ferris is a professor of history emeritus at the University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill and an adjunct professor emeritus in the Curriculum in Folklore. Ferris was chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities from 1997 through 2001, cofounder of the Center for Southern Folklore, and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi. His scholarship has taken the form of print, sound, film, and photography in an academic career including work on African-American folklore and culture.)

In the early seventies when young people sought relevance in all things, including the humanities, Nancy Moses, a graduate student, worked on a planning program for grants for younger scholars. These NEH grants went to filmmakers and researchers who were just getting a foothold, “younger than thirty-five,” Moses remembers. “We wanted to train them as independent, entrepreneurial scholars.” Ron and Fay Stanford, recent liberal arts graduates from Grinnell College in Iowa, received one of these grants. The following excerpts from Ron Stanford’s book Big French Dance tell the story of how the funds facilitated the work the Stanfords had begun on their own, photographing and recording Cajun and Creole musicians in Louisiana’s Bayou Country in 1972, at a time when the traditions and values of the rural populations of the French-speaking parishes were in jeopardy of vanishing. —SM

Adapted from Big French Dance by Ron Stanford

Having no career plans after college, Fay and I decided to move to southwest Louisiana to study French music. In 1972, that seemed to make sense. I knew a little bit about Cajun and zydeco music because for a couple of summers I had a job helping to produce the Smithsonian’s Festival of American Folklife. It was there in D.C. that I heard The Balfa Brothers’ irresistible tunes, and when I returned to Grinnell College in the fall, I hired them to drive up to Iowa for a weekend folk festival in February of 1970.

The band consisted of Dewey Balfa, his brothers Rodney and Will, accordionist Nathan Abshire, and Rodney’s son, Tony, on triangle. We put them up in a couple of spare dorm rooms. One snowy night, they shared their whiskey with us. Late in the evening, Dewey, who was already an ambassador for Cajun music, said earnestly, “Mais, Ron, you should really come live down in Louisiana someday.”

Fay and I left Iowa a couple of years later, having graduated with liberal arts degrees. After experiencing several weeks of underemployment back home in suburban Washington, I remembered Dewey’s invitation. I called information, dialed Dewey, and asked if he recalled inviting me to Louisiana. Without hesitation he assured me that we were welcome in Basile.

We now had a destination and a vague mission: to do a survey of the regional French music and to record an album that would include extensive liner notes and some photographs. Maybe we could get a grant from a government program that I had heard about. Since our stark lack of knowledge made us feel ill-equipped to write a grant proposal, we decided that we might as well move to Louisiana and write it after we’d had the chance to look around.

In early September of 1972, we arrived in our new hometown. Fay and I had only a few hundred dollars remaining from our wedding envelopes, so we were highly motivated to quickly crank out a grant proposal. Because of Dewey’s relationship with Floyd Soileau, founder and owner of Swallow Records, we were able to obtain a commitment that he would release our first record, along with a promised booklet of articles and pictures.

The Cajun Music Research Project was born, at least as a grant proposal.

In the meantime, we had no trouble finding work—because having the Balfa family on your side was like having a VIP backstage pass in the Basile-Mamou-Eunice Triangle. When Mr. Landry, the principal of Basile Elementary, found out (probably from Dewey) that two new college graduates had just moved to Basile, it wasn’t long before both of us entered the work force as substitute teachers. I “taught” for only a couple of days, but Fay’s talents were more in demand, and she was hired regularly for several weeks. The outcome of our short teaching careers was a new telephone line. In order for us to work at the school, they had to be able to call us. We lived at the end of a rutted, one-lane, quarter-mile driveway off U.S. Route 190, a couple miles east of Basile. At first, Mr. Landry would drive out to our house early in the morning to tell us that they needed a teacher that day, which got old for him pretty fast. He pulled some strings at the phone company, and in short order a bunch of poles went in from the highway to our house, strung with the precious lifeline.

I found an entry-level niche in the local construction industry, pulling down $2 an hour.

My last construction job was at a Eunice building supplies company, working on a crew digging the footings for a new warehouse. I was best known on the job as the guy who broke three shovel handles digging in the Louisiana muck. My W-2 from that job shows total earnings of $540; it took me seven weeks of backbreaking labor to earn that sum. One day in the first week of March of 1973, the owner called me into his office to have a word, and, to my surprise, he offered me a promotion to manager of the yard. I accepted the position, and I must have thought it was the perfect time to ask him if I could please take off the next Tuesday so I could photograph Mardi Gras. He fired me right on the spot.

Just in the nick of time, the U.S. government awarded us a Younger Scholars grant in the amount of $5,513. We were now able to devote our evenings to taking pictures in dance halls and meeting musicians. We’d spend our days following up with the artists in their homes, conducting interviews, taking more pictures and sometimes recording music. It was so easy to meet people, and nearly everyone seemed flattered that we wanted to take their picture and hear their story. Our full-time job was to conduct research into the area’s French music and to find just the right combination of musicians for a record album.

I had done a bit of photography before moving to Louisiana, but I was determined to learn on the job. I lined the smokehouse with tar paper to keep out the light and made a safe light by spray painting a mayonnaise jar yellow and putting a bulb inside. My enlarger was a beautiful old Beseler that I found in a Lafayette camera shop.

The fruit of our grant was a compilation LP with accompanying booklet called J’Étais au Bal: Music from French Louisiana, released on Swallow Records in 1974. Our musical survey included everything from an unaccompanied ballad sung by an elderly woman who had lived her whole life in Eunice and couldn’t speak a word of English, to Cajun and zydeco dance bands, to the south Louisiana rock ‘n’ roll now called Swamp- Pop. The album was a collection of our field recordings, several tracks we recorded at the studio in Ville Platte, and re-releases of four Swallow hits.

J’Étais au Bal was released as we were leaving Louisiana in the summer of 1974, and that was the end, or so we assumed, of our Cajun Music Research Project.

In 2016 I rediscovered my old box of negatives that I had been moving and storing for more than 40 years. Over the course of a few months I scanned them, and thanks to digital technology I began to see how much I had missed the first time around. I still had my old dog-eared, smokehouse darkroom contact sheets with their tiny pictures, most of which I had never thought worthy of printing. I didn’t really appreciate what was in the trove until I started making large prints from the retouched image files. Seeing my pictures in high resolution, I was led back into that musical world.

In reopening the project, I became curious about several rolls of images whose subjects I couldn’t identify. In a few cases, neither of us could remember anything about a particular dance hall. If the music wasn’t what we wanted for our record, we moved on, sometimes without writing notes. I posted a few of these unidentified clubs and musicians on social media, and it didn’t take long for several Louisiana musicians to respond.

One of these players is a thirty-two-year-old traditionalist named Christian LeJeune, who found my photographs on Instagram. Christian helpfully answered my questions and proved knowledgeable about the music scene that we experienced a decade and a half before he was born.

He speaks beautiful Cajun French. His band, Quatre Coin Throwdown, has such raw energy and authenticity—down to the minimalist recording technique—that I couldn’t help but recall being out at some hunting camp in 1973 eating squirrel sauce piquante and pounding Schlitzes.