In 1921, New Yorker Rosie Calinetti professed her intention “to be the greatest actress that the world has ever seen.”

According to a bemused New York Herald reporter, Rosie was seven or eight years old, lived on Mulberry Street near Canal, and went to the movies every chance she got. She was “tremendously impressed” with a newsreel of a queen being driven around her city, but had mistaken her for an actress, thinking “all the pomp and circumstance were due to her great ability and reputation.”

Rosie might be forgiven for her mistake, because newsreels at that point were, well, new. Also they were silent. Sound wouldn’t come until the Fox Film Corporation brought Movietone technology to films in 1927. And newsreel producers frequently blurred the line between news and drama.

We don’t know whether Rosie Calinetti held on to her dream of movie stardom or changed aspirations with the next reel she saw. What we do know is that newsreels gathered and enthralled audiences until the 1960s, when people looked to flickering televisions rather than to movie theaters for their news. And though the newsreel may be history, vast collections of it remain, much of it unseen.

Eleven million feet of newsreel now live at the University of South Carolina in its Moving Image Research Collections, where curators, archivists, and preservationists work to preserve this material and open it for public viewing.

Donated by 20th Century Fox in the early 1980s, the footage spans the silent era through the Second World War. “It’s very rare, actually, for silent newsreels to be extant,” says director of Moving Image Collections Heather Heckman. “A lot of it is lost,” she explains, because “it was seen as ephemeral by studios that made it.”

Even later newsreel footage with sound is seldom available to the public, and not with the context and organization provided by the USC library team. The Fox Movietone collection is the largest set of newsreels freely available online, with thousands of stories meticulously organized and described. (The UCLA Film & Television Archive holds the Hearst Metrotone News Collection’s 27 million feet, but most of that is not available online.) USC also has the newsreels’ “dope sheets,” the accompanying paperwork filled out by cameramen describing each piece of film, including notes, shot lists, and often other materials relating to the stories such as clippings and articles. The footage holds historical interest, and also the innocence of an earlier time.

Newsreels show a day on a farm, whales in the Pacific, a trip through upstate New York’s Ausable Chasm, a visit to the president’s summer camp, marathon runners, mountain trappers, and political conventions.

At the fourth annual wood chopping and sawing contest in Skytop, Pennsylvania, a woman identified as Mrs. Berger accepts a newspaper-wrapped prize, chuckling, “Mom, I’m bringing home the bacon.” Two men wheel the “latest flivver plane” out of a barn, then take off and land on the beach as the inventor touts this cheap solution for people in rural areas who “can’t get anywhere.” During Prohibition, the U.S. Coast Guard displays a “Rum Runner” schooner captured off the Massachusetts coast. Sailors dynamite the ice around the trapped Soviet expedition ship Chelyuskin, judging this a “brilliant chapter of human struggle against the elements” and avoiding “another arctic tragedy.” The New York Giants begin their first day of spring training in Miami. Two men shake their heads theatrically at a “Closed—Blue Laws” sign posted at a gas station; the camera pans to a sign for “Bootleg Gasoline, 49c/gal.,” instructing interested parties to “call at back door.”

If you watched newsreels in theaters, you probably remember dramatic music, narration, and quick cuts, but this collection has little of that. It consists mostly of raw footage, about 90 percent of which was never used on the big screen.

Some of the film is lighthearted, some serious—and some in between. Because the newsreels themselves were edited and the footage occasionally staged, historians and scholars have debated their value as artifacts. But the editing reveals assumptions and priorities. And the massive collections provide a valuable glimpse into bygone times.

Worth the Price of Admission

After Charles Pathé produced the first silent newsreels for American audiences in 1911, theaters across the country showed them with great fanfare. Communities shared and interacted with news near and far.

“The Pathé weekly is shown at the Rex every Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday and a new Pathé Weekly at the Cozy, Thursday, Friday and Saturday. This Pathé Weekly alone is worth the price of admission,” noted a theater column in a 1915 Boise, Idaho, newspaper. Residents would “regret it” if they missed the weekly and the Keystone comedy, which would “be the talk of our city.”

Communities didn’t just gather to watch the news but also to make it. In 1913, Tennessee’s Columbia Herald newspaper breathlessly reported on Pathé plans to film their mule market. Being featured in a newsreel showed that “the fame of Maury County as a mule market is not confined to Tennessee and the South alone” but “at once puts Columbia in the national class.”

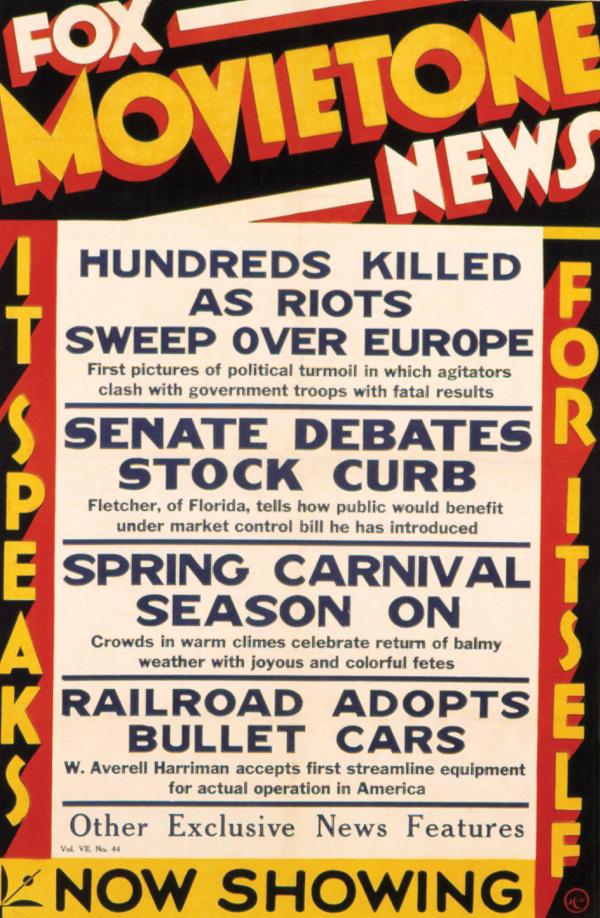

Fox Film Corporation soon changed the game by incorporating sound in newsreels. “The Event of Events! Our Screen Talks!” cried an Elizabeth City, North Carolina, newspaper. “And now you’ll hear voices as natural as the human voice as they speak from the screen through this 8th Wonder of the World.”

“Fox tried to differentiate themselves by pushing the idea that they could go out into the world, not just record in studios,” says Heckman, enabling us to “experience the place and the sounds in the place as well as the images.” Audiences first saw, and heard, the 125th United States Military Academy anniversary commemoration in 1927. The newsreel “enables the spectator to hear the military band play,” marveled a Washington, D.C., newspaper review, and “the orders of the commanding officers. Even the transfer of the guns from one position to another is made distinctly audible.” That summer, newsreel of Charles Lindbergh’s nonstop flights to Paris and back produced crowds so great that the same newspaper advised readers nearly two months later that “this Movietone subject is still being shown at the Roxy, in New York.”

Newsreels were chock-full of the unforgettable details that make professional and amateur videos go viral today: the clamor of little boys playing sandlot baseball, the judging of a “Miss Grandma” bathing beauty contest at Steeplechase Park, three-year-old golf wunderkind Eddie Rule boasting “I can even hit it blindfolded” as he tees a golf ball on his grandfather’s head and then gives the ball a whack.

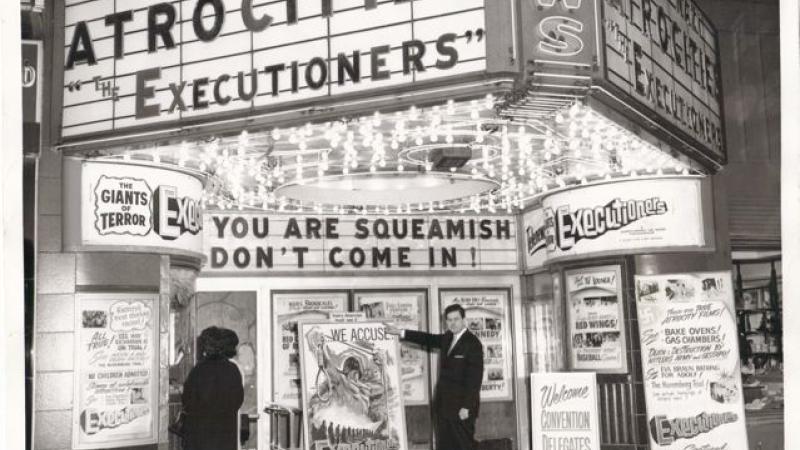

By the 1930s and '40s, newsreels warmed up audiences waiting for feature films. Companies opened theaters dedicated to newsreels, including the Embassy in New York, the Trans-Lux in Washington, D.C., the Telenews in Detroit, and the Regent in Oakland, California. Luxury train lines like the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Jeffersonian offered a newsreel theater on board.

Scholars estimate that at least 40 million people in the United States and more than two hundred million people worldwide watched newsreels each week in the late 1930s. And perhaps neither the filmmakers nor their audiences grappled too hard with the question of their historic significance.

Newsreel companies sent cameramen and sound trucks all over the world, even strapping a camera to a bobsled ready to plunge down Mount Van Hoevenberg during the Olympic Winter Games at Lake Placid.

Cameraman Charles Peden described getting his first assignment right before he was supposed to be married. The task? Film some goats eating shirts. “Ideas for sound pictures were simple in those days,” Peden reflected. “Any new sound was a subject, and someone thought that tearing linen made a r’aring sound on the film.” This breaking news being a top priority, he left his “wedding rehearsal cold to hunt for some goats that would eat shirts.”

Newsreel crews filmed everything. The mysterious crash of an airship on the shore of the English Channel. Earthquake destruction on Melfi, in Italy. Iron workers having lunch on a New York skyscraper beam. President Hoover’s swearing-in, and ex-President Coolidge dressed as a cowboy. And “every sort of blast,” according to cameraman Peden, from bombs to explosions at sea.

With more serious news than goats eating shirts or machines making doughnuts, companies got the big events out fast. The film of Lindbergh’s return to the U.S., for example, sped along on a three-car train that held a developing laboratory, a projection room, and an editorial office. Newsreels also captured wars, political events, and other weighty subjects.

What made it into the final newsreels shown in theaters and trains was only a small portion of the footage captured. “They were making judgments as all journalists and editors do,” says Moving Image Research Collections Curator Greg Wilsbacher, “for the here and now, not necessarily for posterity.” Most of the time, extra footage was carefully stored in the Fox library in New York. Or, sometimes, not. Wilsbacher points to the visual importance of cameraman Al Brick’s films of Pearl Harbor on the morning of the Japanese attack. Brick’s images, used by the Navy Department and Fox Movietone in approved newsreels, quickly became the quintessential representation of the attack. But while Wilsbacher says that Brick filmed all day and into the night, documenting the second wave of the attack and fires burning in the harbor, he turned over his film to the Navy and little raw footage of that day remained in the Fox library.

Newsreels were pivotal in bringing news of 1930s conflicts in Europe and Asia, and then World War II, back to the home front. During the Second World War, the War Department and the Office of War Information “were deliberative in the way they handled motion picture film images,” says Wilsbacher. Due to concern from the White House “that the American people weren’t seeing enough graphic footage and weren’t aware of the level of violence American soldiers and sailors were going to be experiencing,” the War Department authorized more filming and release of graphic combat scenes to make clear to the public the human stakes of war—for example, in footage of the horrific losses at the 1943 Pacific Battle of Tarawa.

Whether shot by armed services personnel or newsreel cameramen like Fox Movietone’s Al Brick, Hearst’s Jack Lieb, or Time Life’s Robert Capa, film shot overseas was vetted and censored by the Office of War Information and the War Department and then repackaged. “Every newsreel company got the same allotment of film,” according to Wilsbacher. Questions about authenticity and methods—and even accusations of fakery—have appeared in the years since the war. The surrounding outtakes, dope sheets, and documentation of editorial decisions in the Fox Movietone collection provide critical context for the fever-pitched newsreels of the 1930s and 1940s.

The mix of the monumental and the mundane give the edited newsreels a back-in-time feeling, and the expansive footage left behind provides a bigger picture. One of Wilsbacher’s favorite examples is film of Charles Lindbergh as an airmail pilot, flying the inaugural air mail run between Chicago and St. Louis in 1926. The newsreel company at the time didn’t even think it worth recording his name—he was only an anonymous pilot. But the next year the cameraman sent an urgent telegram to Fox: They already had footage of the now-famous pilot in their vaults!

By the 1950s, television had become the public’s preferred method for news consumption. Newsreel theaters closed their doors, and the last American-made newsreels ceased production in 1967. But the medium is not lost entirely; what survives helps open a window on the sights and sounds of the past.

Researchers, filmmakers, and writers have already used the Fox Movietone collection. Footage of people rowing ghuffa boats along the Tigris River in Baghdad in the early 1900s became the opening scene for the recent movie Letters from Baghdad. Historian Melissa Cooper watched outtakes of President Calvin Coolidge’s 1928 vacation to Sapelo Island, Georgia, and found an early fascination with African-American Gullah islanders and their culture. Greg Lambousy, director of the New Orleans Jazz Museum, identified longtime street performer and jazz artist “CoCoMo” Joe Barthelemy from outtakes of him dancing as a child in New Orleans. And film preservation experts painstakingly adjusted and stabilized outtakes of Babe Ruth hitting a home run and rounding the bases in a 1931 game against the Red Sox—film that is now shown each year to hundreds of thousands of visitors to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

For Heckman, the collection’s range is also illustrated by a clip of children in New York’s Central Park, in which “the cameraman is having them, for some reason, fake laughter.” Still, she finds it charming. Just like today, she says, “a hundred years ago, people liked kids and pets.”