In November 2018, French president Emmanuel Macron pledged to return 26 artifacts housed in French museums that had been taken from the African state of Benin during the early days of colonialism. More recently, Germany adopted a new policy to return items collected under circumstances that would be considered illegal by today’s standards and pledged 1.9 million euros of research funding to ascertain the origins of holdings in its cultural institutions. The British Museum, which has committed to lending out more of its holdings instead of returning them to the nations from which they were taken, faces criticism for failing to confront its role in the continuing damage of colonization.

Even as governments around the world begin to confront their colonial histories, the most visible conversations about Indigenous property rights have centered on the policies, anxieties, and opinions of non-Indigenous leaders. Kim Christen, the director of the Digital Technology and Culture Program at Washington State University, has developed a tool for Indigenous people to recast cultural materials within their own experiences and histories.

Over the past two decades, Christen has collaborated with Indigenous communities to build a tool that responds to their specific needs. Mukurtu, a digital access platform for managing and curating cultural heritage materials, has developed from a decadeslong dialog with community partners about how to build digital tools around well-established expectations for how cultural heritage should be kept and shared.

Mukurtu grew out of Christen’s long-term relationship with the Warumungu community in central Australia. Warumungu community members had collections of photographs and other cultural objects they wanted to share, and they partnered with Christen to develop a digital tool that would enable them to do so in culturally appropriate ways. For instance, it was a commonly accepted practice among the Warumungu not to display images of deceased relatives or to provide access to traditional knowledge based on kin relations. Christen and her team spent years working with the community to develop a tool that could meet these standards, and they came up with an alpha version that enabled community members to determine who could see and interact with materials.

From the beginning, cultural protocols—standards indicating who should have access to what information under what conditions—were central to Mukurtu’s design. In the same way that many social media platforms allow users to post publicly or limit sharing to specific groups, Mukurtu’s design allows its users to make decisions about access. Through its customization options, users can preserve generations of shared practices and shades of nuance within communities. A community might set cultural protocols to determine, for instance, the appropriate circumstances under which to display photos of a deceased relative, or the right time of year to play a harvest song. A community might circulate content only to women, elders, or spiritual leaders, or, indeed, they might choose to open records to the public. With complete autonomy to create protocols and approve user accounts, communities themselves determine the rules of engagement.

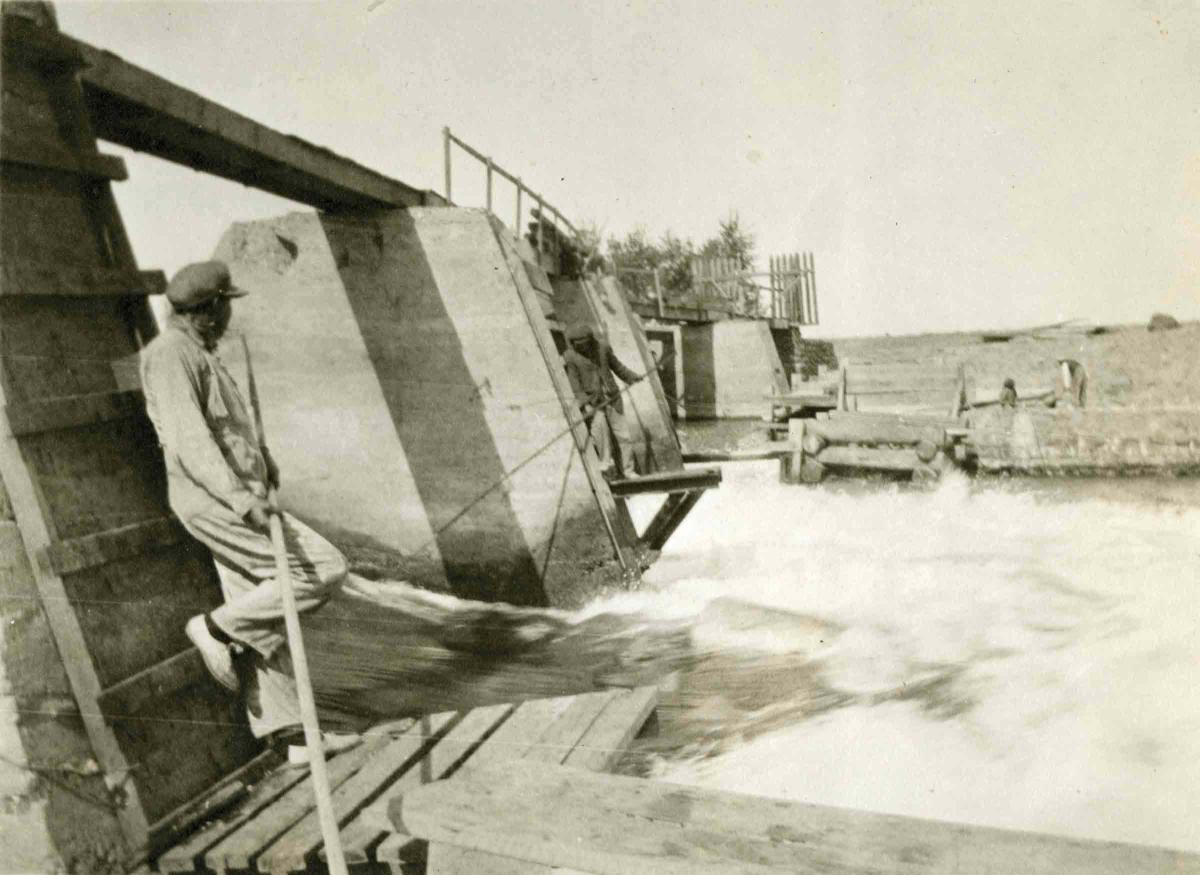

When the Mukurtu team began working with Native American nations in the Inland Pacific Northwest to tailor a new version of the platform, they had to make some major changes. The Warumungu had started with a collection that had been assembled, in large part, from belongings that missionaries and scholars had returned to the community. The Plateau communities they worked with, on the other hand, were dealing with digital and physical materials scattered through cultural institutions across North America. Many of these materials had been, as Christen puts it, “collected under very dubious circumstances.”

Just as the British Museum’s halls are filled with imperial loot, such as the Rosetta Stone and pieces from the Parthenon, many of North America’s most prestigious libraries, museums, and archives have an unsettling history of taking without asking. “We’re talking about the colonial roots of these materials,” says Christen, “These institutions are built and founded on those colonial records, on histories of violence—histories that are based in genocide and erasure.”

The ways that non-Indigenous institutions describe their Indigenous holdings can be problematic, ranging from sparse, to racist, to entirely false. While the Warumungu had developed their metadata—the information about the materials in their collection—internally, the first North American communities to adopt Mukurtu had to contend with a sea of misinformation, says Christen. “Communities were saying, ‘Well this is wrong. That’s not that person—that’s my grandfather.’”

Through Mukurtu, communities were able to present objects from their cultural heritage in context, providing rich histories and cultural explanations and, often, revising problematic descriptions from existing records. Many of Mukurtu’s early adopters saw the multiple counternarratives as part of the story. “Nobody wanted to erase those original records, or delete the scholarly record,” says Christen, “but everybody wanted to have a voice and have it be prominent in its display.”

This ability to offer multiple perspectives on the same object is one of the hallmarks that sets Mukurtu apart. “Other content-management systems rely heavily on the notion of ‘the one authority record,’” says Christen. “It’s a way of thinking about the world that’s very Western.” When mainstream libraries, museums, and archives catalog their holdings this way, the privileged voice is rarely the Indigenous one. “Their information, their stories, their narratives, their knowledge gets erased, and the knowledge that is put forward as the authority is the non-Indigenous scholar or collector.”

Mukurtu, in contrast, allows for multiple narratives to exist in tandem. Michael Wynne, digital applications librarian at Washington State University, gives the example of a basket created by a member of the Warm Springs Tribe and physically held at the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture. On the Mukurtu platform, both the museum and the Indigenous nation have community accounts, and each has uploaded its own record for the object. In the NMAC’s tab, it is called a “root gathering bag” and accompanied by brief information including subject headings, a date range, and a general physical description.

Click the next tab, and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs record uses a new title, “Wasco Man Basket,” and cites three expert weavers who, in addition to providing a richer set of key words, have also added three separate textual and video narratives describing the design and cultural significance of the bag. In a video, one of the elder women describes the basket in her native language and then redescribes, in English, its cultural significance. The museum’s description “really doesn’t tell you anything about the basket,” says Wynne. “In reality, when people can tell their own narratives, you get so much more valuable information. There is so much more life in these records.” For Wynne, records created by the tribes themselves reveal active and engaged people. “A lot of dialog around communities is in a past-tense historical,” he says, “but this is so much more of a living object.”

As Indigenous communities use Mukurtu and cultural institutions have begun to negotiate how to present digital records for Indigenous materials, the conversations over the past five or more years have given way to more nuanced and collaborative discussions about “ethical curation and digital repatriation,” says Christen. Where it was common that transactions were one-directional, with libraries, museums, and archives providing digital copies, now they are “working in collaboration, and communities using Mukurtu can share back information, traditional knowledge and provide updated language.” For Christen, this dialog and sharing are a crucial step in relationship-building between Indigenous communities and cultural institutions. “One of the ways that repair—reparations—can work in institutions is by not only providing those digital materials back, but working in conversation and working collaboratively to update and expand those records and highlight Indigenous attribution and authority.”

In the case of the Ancestral Voices project, the Passamaquoddy Nation and the Library of Congress landed on a solution that worked for both sides. The Library of Congress had acquired the first wax recordings of Indigenous voices in North America—a collection of wax cylinders through which Jesse Walter Fewkes had recorded the voices of members of the Passamaquoddy Tribe in 1890. In danger of degradation, some of the wax recordings had since been restored and made available digitally through the library’s online catalog. After the library repatriated the digital files to the Passamaquoddy, the community used Mukurtu to create records with rich knowledge descriptions and traditional knowledge labels indicating attribution and other protocols. “Mukurtu has been situated as a connector in that way. It allows communities to re-narrate and add their knowledge, traditional narratives, and provide those back to institutions.”

Hosting a Mukurtu site requires the technical means to host the site as well as the human resources to maintain it, make decisions about how it will be used, and manage the collections. “This is one piece of the puzzle,” Christen says. “The technology is something that launches us into relationships. It doesn’t create the relationships. It doesn’t sustain them. It doesn’t negate the need for labor and infrastructure.”

As universities and cultural institutions of all types look to treat Indigenous knowledge in more culturally appropriate terms, Christen cautions against giving too much glory to the role of technology in these efforts. “I really try to temper any sense of Mukurtu or any digital tool as ‘revolutionary’ or as ‘saving,’” says Christen. “Who’s going to do it are the people who want to do it.”

“I don’t want to tell a story about Mukurtu as a digital platform alone,” Christen says. “I want to tell a story about Mukurtu as a connector, as a relationship builder, as something that provides a stage for ethical conversations and ethical structures. Twenty years from now, Mukurtu might be gone, but these relationships that we put in place are still going to be there.”