In the late 1890s, bicycle racing became the first modern international sport.

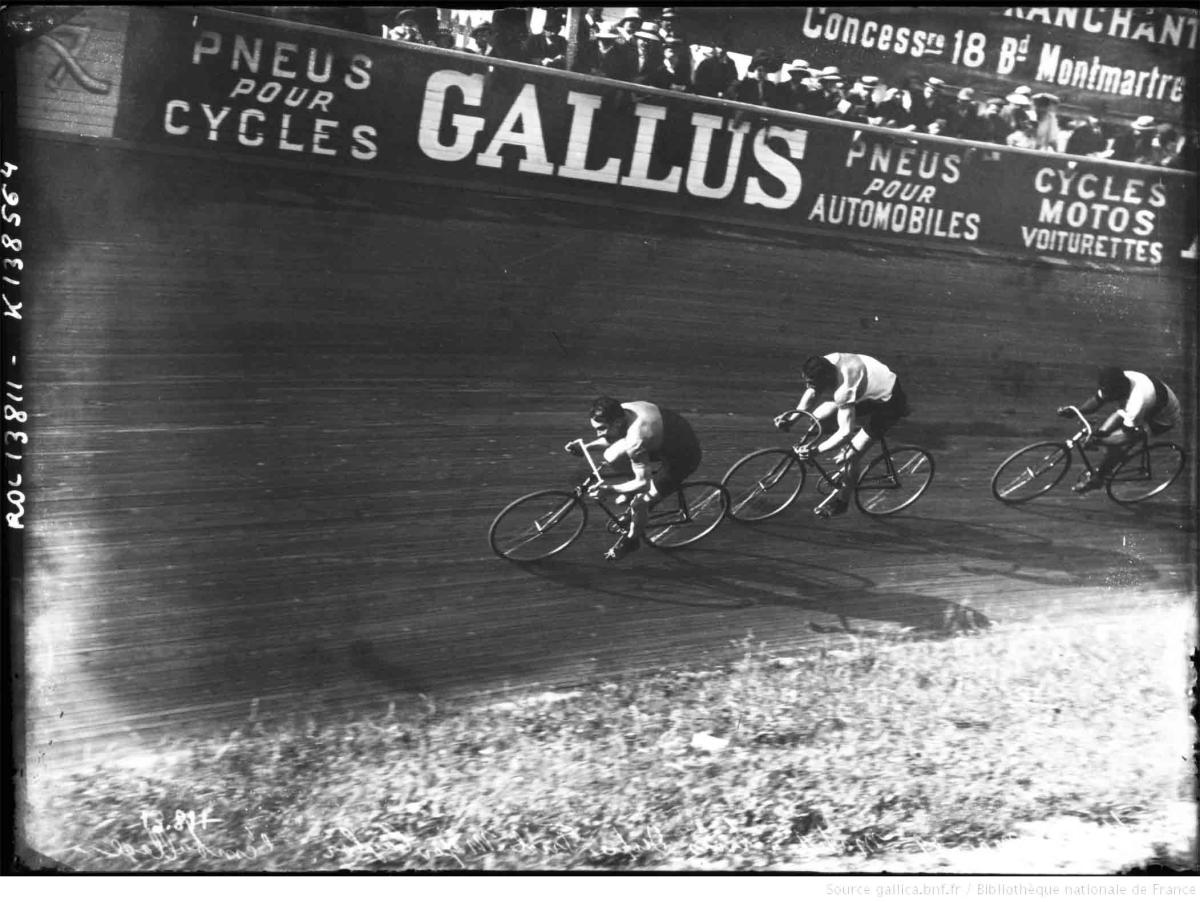

It towered over basketball, a new sport just then spreading to college campuses around New England. American football and soccer were niche pastimes, about as popular as badminton. Bicycle races, like horse racing, drew more spectators, greater press coverage, and bigger money from coast to coast than did professional baseball. Cycling also ignited passions across Europe and Australia. In the mauve decade, as it was called, countries took turns hosting annual world championships.

A throng of newshounds in suits and straw boaters converged in August 1899 on Queen’s Park in Montreal. Reporters and illustrators from big-circulation publications on both sides of the Atlantic came to cover the world cycling championships. Huge white tents, pitched around the park, accommodated the fastest riders from Australia, Canada, France, Great Britain, and the United States. Vendors touted food and drinks. Large bands took turns in the middle of the track beating out popular tunes.

It was a chance to watch powerful athletes on bicycles and to see something few attendees had ever encountered: a Black person. His name was Major Taylor. The twenty-year-old cyclist, born in Indianapolis, was the first African American many Montreal spectators had ever come across. Years before the Great Migration in which millions of Black people left farms in the South to come north, Black people were practically nonexistent in Montreal and thereabouts.

Taylor stood five feet seven inches tall, average for men of his generation, and weighed a muscular 160 pounds, built up from cross-training in YMCA gyms and punching the heavy bag. He rode in a modern aerodynamic position, thanks to his innovative steel handlebar, which extended over the front wheel. Stretching forward, he rode with his back flat as a table, elbows tucked against his sides, nose almost touching the handlebars. His rivals rode with their heads up and chests high, catching headwinds that Taylor ducked. He smiled under center-parted, closely barbered curly black hair. His dark brown skin was smooth. He admitted to being vain about his racing colors—a snug wool jersey trimmed with a black collar and cuff bands, and the rest as blue as a clear summer sky.

The man in the blue jersey specialized in sprinting. It was the late Gilded Age, when sprinters with lightning in their legs attracted paying crowds like tenors to an opera house. Riders sat on a leather saddle, shoulders and heads steady as they spun their legs. A quick boost in pedal cadence by ten strokes per minute could open a sudden gap and put victory within reach. In this elite ultra-competitive event, Taylor reigned as national professional sprint champion and held the prestigious world-record time for the mile.

The Montreal worlds opened on Monday, August 7. The main event was the half-mile championship for pros. Eighteen thousand fans filled the sold-out grandstand and bleachers, and five thousand more were turned away. In the morning, Taylor won two frenzied qualifying heats, against packs of more than a dozen ambitious opponents, to advance to the afternoon final against seven rivals, primed and confident.

The half-mile final launched with more elbow flicking and jockeying for position than speed. Around the final turn, Charlie McCarthy of St. Louis took over, legs pumping like pistons. Taylor tucked behind his rear wheel while the rest followed. When they swept onto the final straight, a flock of challengers swarmed beside Taylor like birds roosting. He finally spotted an opening, knifed through traffic, and pipped McCarthy at the line.

Judges from Canada, France, and the United States deliberated on the infield by the finish. A church-like silence fell. A judge standing in a white linen suit before the grandstand pulled an oversized megaphone with both hands to his face. He broke the stillness when he bellowed that McCarthy won, Taylor came in second, and Nat Butler of Cambridge, Massachusetts, placed third.

Thousands of spectators, including the mayor of Montreal, Raymond Préfontain, watching from a box seat opposite the finish line, jumped to their feet and hollered in protest. They shouted that Taylor had won. Boisterous hissing, booing, and insults aimed against the judges carried on for half an hour.

When the ruckus subsided, Taylor dismounted near the judges’ stand. He walked up to one of the judges and asked if that was their honest decision—a Black man challenging white officials in front of the audience. When informed that was the case, he said with composure that he would abide by the decision, but added he knew he had won.

He could afford to sacrifice the half-mile. He later wrote he won by a foot. (The use of cameras to take finish-line photos was still more than a decade away.)

Taylor had a sense of his place in cycling history. At age fourteen, in Indianapolis, he was mentored by Louis Munger, a former star racer who turned to manufacturing racing bicycles that weighed a mere 21 pounds. Telephones were a novelty when Munger hired Taylor as a messenger. Sometimes they rode together and Munger offered coaching tips. They practiced bike stunts as well, which put Taylor in good stead years later in tight situations on the track. Munger predicted that if Taylor trained systematically and avoided tobacco and alcohol, he could win the world professional one-mile sprint championship.

Munger, a bachelor, even hosted pals who came to town to race. Taylor thus dined with cycling’s big names, including Arthur Zimmerman, winner of the inaugural one-mile world championship in Chicago at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. His title generated lavish contracts to race in cycling-mad Paris and other cities in Europe and then across the Pacific in Australia.

Taylor, the son of a coachman, always set his sights high. He treated every contest as a step toward winning the world one-mile sprint title. It was not for the prize money that he raced in Montreal. Winning the professional title there paid $200, a paltry sum compared with the $875—worth $28,300 today—he recently took home after winning the one-mile open and two-mile sweepstakes on Charles River Track in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Dollar bills were one-quarter larger than today, and there were no taxes, so he took home a handsome roll of cash.

Of the dozens of events from the half-mile to the one-hundred kilometers contested in Montreal, the one-mile professional sprint title rated as the most important, the sport’s highest honor, and, with the Tour de France still four years over the horizon, cycling’s undisputed crown jewel.

The one-mile championship was set for the next day. Taylor walked away from the judges’ stand, accepting three hard-earned lessons—that he had to avoid getting blocked, that winning depended more on timing than speed, and that next time he had to win by a wide margin.

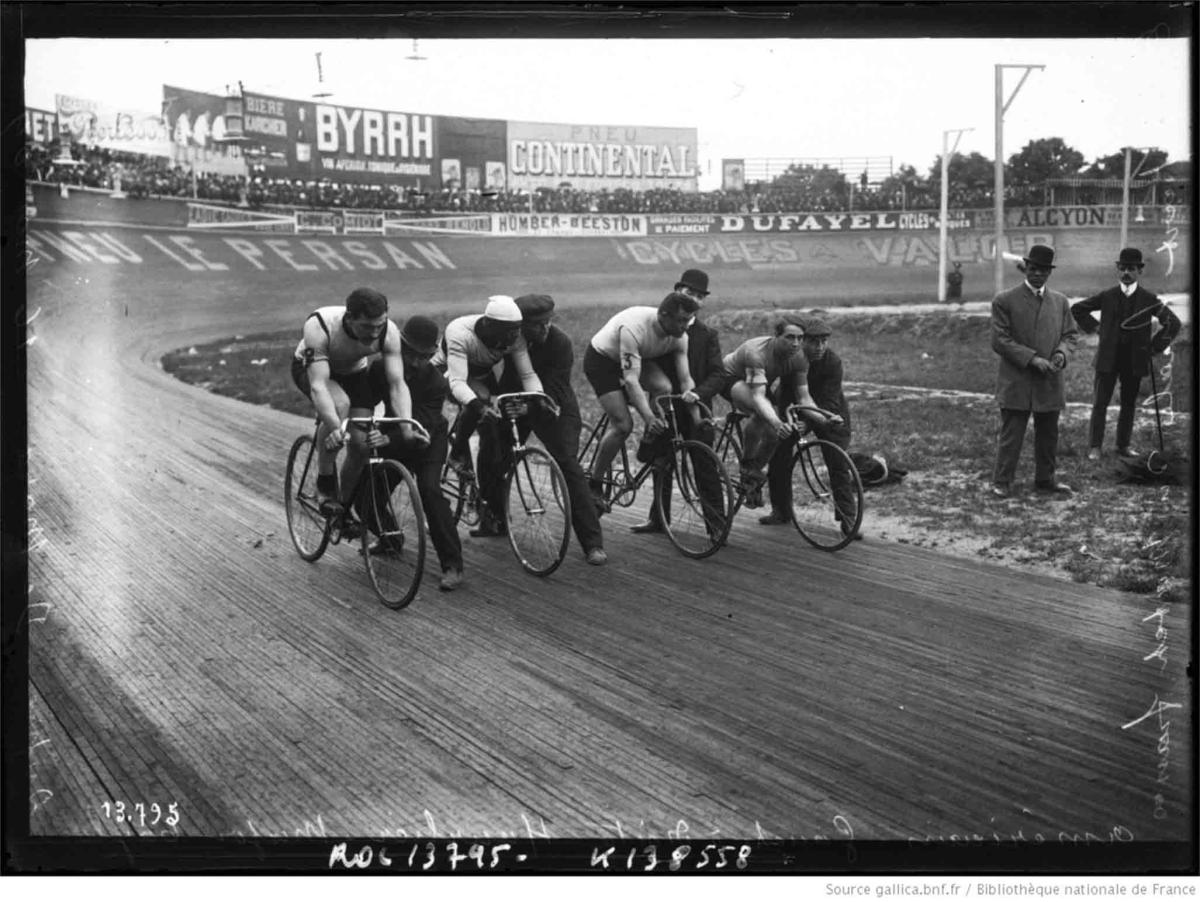

On the morning of Tuesday, August 8, Taylor joined 20 other pros in five heats for the one-mile sprint championship. Only winners advanced to the next round. In two qualifiers, Taylor lined up, balanced on his bike, shoulder-to-shoulder with rivals spread across the track, 25 feet wide. Trainers bent at the waist to hold the riders in position, and the riders leaned forward, ready, coiled like compressed springs, waiting for the starter to raise his arm and fire a revolver into the sky.

Taylor won his heats to reach the early-afternoon final. He faced Canadian champion Angus McLeod, tall and boasting a mat of wavy dark hair; France’s Gaston Courbe d’Outrelon, easily spotted with the blue, white, and red stripes of France’s tricolor flag wrapped around his waist; and Nat and Tom Butler. Taylor admitted afterward that he was a trifle nervous about the brothers—they had set national records and could, in effect, ride as a team.

As the finalists gripped their handlebars, a hush fell over the audience—strangers united in a moment of anticipation. At the crack of the starter’s pistol, they took off in a tight bunch, bumping shoulders for position through turns. They upped the pace on the second lap down the back straight. On the last lap, Nat Butler charged at top speed into the lead and the crowd roared. Taylor chased, with Tom Butler, d’Outrelon, and McLeod following as close as train cars.

With 250 yards left, McLeod bulleted ahead. Taylor swiftly caught and passed him while looking back under an arm to check on the Butlers. They rounded the last turn together and fanned out on the final straight, shoulders and front wheels almost abreast.

“It was a beautiful sprint,” said the Montreal Star. “Tom Butler drove down for the finish at a great rate. Taylor caught him ten feet from the line.”

Taylor surged to win by a wheel.

D’Outrelon claimed third.

A judge bellowed through his megaphone that Taylor won. Eighteen thousand spectators responded with thunderous applause.

The Star’s anonymous reporter wrote: “The hold which Taylor has taken upon the sympathies of the people in the grandstand is something wonderful.”

Taylor took a victory lap. “I never felt so proud to be an American before,” he wrote in The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World. He waved a huge bouquet of red roses as the orchestra struck up “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Yet Taylor remained vexed about having lost the half-mile. Right after winning the one-mile world title, he entered the two-mile open championship. He dominated his qualifier heat. Thirty minutes later, in the final against half a dozen rivals, Taylor dashed wide around the outside to win. Tom Butler followed for second, and McCarthy claimed third.

Taylor became the first African American to win a world cycling championship.

Taylor successfully defended his national title, based on points awarded to win, place, or show in designated races over the 1899 season in the turbulent period of Jim Crow racial segregation.

Time after time, from Syracuse to San Francisco, restaurants and hotels refused to serve Taylor. Promoters in the South rejected his race entries outright. The U.S. had several hundred Black cyclists, but they stayed amateur and competed in events only for Blacks. Taylor had the exceptional talent, confidence, and heart to reach the top ranks in spite of the racial prejudice of the era. Every victory showed audiences—and promoters—that he held his own against the fastest whites.

Retired National Basketball Association player Darnell Hillman, a six-foot, nine-inch African American who played for the Indiana Pacers, told me that pioneer Black athletes, like Taylor and Major League Baseball’s Jackie Robinson, suffered tougher physical demands and harsher mental pressures than whites.

“Trailblazers are on their own,” observed Hillman, nicknamed “Doctor Dunk” for an extraordinary vertical jump that helped him win the 1977 NBA Slam-Dunk Contest. “When one steps up, he steps up for all. It’s very tough for trailblazers. They are on their own, and it takes a commitment because they are on their own. Major Taylor had made a commitment to achievement and accomplishment and to winning.”

Jealous opponents didn’t hesitate to shove Taylor into the infield or knock him down. In 1897, W. E. Becker retaliated after Taylor nipped him for second place in Taunton, Massachusetts. Becker wheeled up and hurled him to the ground. “He then started to choke me, but the police interfered,” Taylor wrote. “It was fifteen minutes before I regained consciousness.” Judges disqualified Becker and ordered the race be run again. Taylor was too injured to start.

Antagonists often tried to force him into a “pocket.” When he drafted behind the leader on the pole, hugging the inside lane, another rider conspiring against him would slide next to Taylor’s right side. A third would sit on Taylor’s rear wheel to block him in. A fourth would swing around for victory and afterward split the prize money with his cohorts. Taylor would often be able to escape by swerving his handlebars to give the rear wheel directly ahead of him a sharp side slap with his front wheel. This skillful move from the former stunt rider invariably frightened the rider ahead, causing him to veer out enough for Taylor to kick through and win.

Prize money by the fistful and the adrenaline boost from winning drove Taylor. So did the respect he earned. On Midwest tracks in Ottumwa, Iowa, and Peoria, Illinois, crowds had cheered only white riders. Yet when Taylor won, everyone applauded him with the same gusto. As he put it, “The public is always with the winner, regardless of color.”

Word of his exploits telegraphed across the Atlantic. A Paris consortium offered him an appearance fee of $10,000—worth $320,000 today—to compete on French tracks in the spring of 1900. Most of France’s renowned grand prix events, paying four-figure prizes, showcased their final on Sundays. Taylor declined the high-income offer because it involved Sunday races.

A devout Baptist, he refused to race on the Sabbath, frustrating promoters and disappointing spectators. He even prohibited his mechanic from touching his bicycle on Sundays. Before Taylor mounted his bicycle for a race, he said a silent prayer. He carried the Bible in his bag and relaxed by reading Scripture.

Around the time of the Paris offer, Taylor lived in Worcester, Massachusetts. Despite his international stature in cycling, he couldn’t purchase a new two-story Queen Anne-style house in the leafy white neighborhood of Columbus Park. The builder didn’t sell to Blacks. Taylor hired a white real estate agent. On closing day, the agent handed the builder Taylor’s certified check, paying for the house in full, $2,850. When Taylor arrived, the builder assumed he was a laborer on an errand. The builder signed the deed and left.

Taylor moved his younger sister, Gertrude, ill with tuberculosis, from Chicago into a bedroom on the second floor. He comforted her as friends and church members visited to cheer her up. In April 1900, at the age of nineteen, she passed away.

That season, Floyd MacFarland of San Jose, California, became obsessed with preventing Taylor from taking another national title. A daunting six feet four inches tall, Big Mac had an intimidatingly lean frame, knees and elbows accenting sharp angles. He looked too big for his bicycle and sprawled on it like a praying mantis. The national handicap champion, he seemed to have the power to catch anybody. But Taylor had sure-fire leg speed and superior timing. When he spotted the finish, he performed like a vocalist singing perfect pitch as Mac hummed behind.

Big Mac’s gregarious personality drew followers in his nefarious schemes against Taylor. Mac and cohorts disliked how Taylor kept his own counsel, never touched alcohol, drinking only water or milk. When Mac harassed him on the track infield or in training quarters between races, Taylor raised his voice and quoted Scripture at him.

As the season progressed, Taylor outwitted Mac and his fawning admirers. Even without competing on Sundays, Taylor led the national championship contest. It culminated in early September with the quarter-mile event on the Newark, New Jersey, velodrome. The country’s fastest sprinters took trains to Newark to compete for points and the $500 first prize.

The program drew a standing-room-only audience topping 10,000—including African Americans. Taylor aced his heats. In the final, his two rivals went so fast from the gun that he drafted until the home stretch. “I came from third position and won by about three lengths,” he wrote, calling the race “my easiest championship victory.” He scored his third straight title.

Paris promoters offered him a new contract to race in spring 1901. Taylor received a $5,000 appearance fee—worth $162,000 today—plus expenses for training, hotels, and transportation. (In the United States, riders had to pay their own way.) He competed on board and cement tracks filled with spectators in Paris and storied cities around France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Denmark, and Switzerland. Of the 57 races he entered, against national champions riding on their home tracks before sold-out audiences, Taylor won 42. He earned more than $10,000 in prize money and appearance fees today worth $310,000.

Returning home to Worcester, he joined the national circuit in August and encountered Mac’s dogged treachery. Mac coached riders on how to work together to beat him. Taylor wrote that the difference between the outlaw Jesse James and his gang of bank robbers and Mac and his crew “was that these robbers used bicycles instead of horses.”

In March 1902, Taylor married Daisy Victoria Morris.

The marriage received celebrity treatment in The Colored American Magazine.

He realized that another national title was impossible while MacFarland stalked him. Nevertheless, Taylor received more invitations from Paris promoters for spring campaigns on the continent. An Australian promoter in Sydney enticed him with an even bigger appearance fee to venture the four-week voyage across the Pacific to race Down Under.

On Taylor’s second outing to Australia in May 1904, his wife gave birth in Sydney to their daughter, christened Rita Sydney Taylor. His daughter went on to call herself Sydney.

In 1910, Taylor retired at age thirty-two after 14 years of professional racing. He competed on three continents as an international superstar, decades before the introduction of commercial airlines. “I was a pioneer,” he wrote, “and therefore had to blaze my own trail.”

Taylor died in June 1932. On September 9, 2021, his hometown of Indianapolis honored him with a 55-foot-tall mural painted on the outside of a prominent downtown office building. Created by artist Shawn Michael Warren, it shows Taylor during his prime years, as an athlete of great power and determination.

*This article was updated on February 25, 2022, to say that Taylor nipped W. E. Becker for second place, not third, in 1897, in Taunton, Massachusetts, not on Charles River Track.