In 1961, Marisol arrived at a panel discussion in New York City in a white mask. Seated alongside four squarely dressed men, the artist was an eyesore. The crowd wasn’t amused. “Take off that goddam mask!” they cried, stamping their feet. She finally untied the strings, revealing her face, painted like a mask.

Marisol was a cipher, says Cathleen Chaffee, curator of the artist’s retrospective at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum. In her wooden figures, hands jut out unnaturally; babies’ heads are improbably large; frenzied pinks and reds abound. A marvelous tension runs through her work. She was a magician, silent, mercurial: now you see her, now you don’t.

Born to Venezuelan parents in Paris in 1930, María Sol Escobar traversed Caracas, Los Angeles, and New York City, her pictures in tow. “I was always drawing,” she recalled, “ever since I can remember.”

When Marisol was eleven, her mother died by suicide. For years, the artist rarely spoke, the sound of others’ voices suddenly irritating, unnecessary. “I didn’t want to sound the way other people did,” she confessed in 1975. In one of the show’s works, Marisol holds an umbrella for her mother, its swirls of acid yellow awash in light. The two, clad in candy-pink gowns, are unknowable: the mother’s grin plastered on, the daughter’s grimace beyond her years. They stand side by side but remain worlds apart.

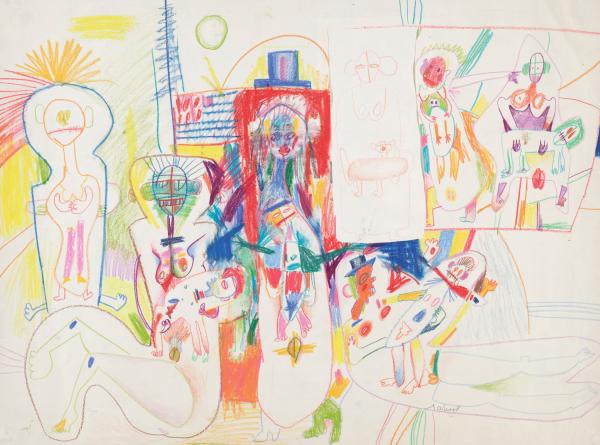

Something was splintering in Marisol, too. An early work on paper, one of the first in the show, reveals a world torn open: bodies gored, lips sutured shut. “It’s Marisol’s Guernica,” Chaffee says.

She has a way of “seeing behind the skin of people,” Chafee continues, laying bare all that is disquieting, unseemly. Blues and reds ricochet. Yellows and greens shock. Every color and gesture is playful and a touch mad.

“The figures need me,” she said. “I need them.” A codependency developed, Marisol and her art bleeding into one. At times, the work frightened her, as when she made a portrait of Richard Nixon. Riding the subway, “everyone would have [his] face.” Especially haunting were his “very tight lips and sort of greyish complexion.” But, more often, her work was a comfort, something to steady her. In her studio, she observed, “I don’t feel alone.”

What Marisol felt, she felt profoundly. In a 1969 interview with the critic John Gruen, she has a charming naïveté. She is often “enthusiastic”; she considers the abstract painter Franz Kline “very romantic.” Throughout, Marisol says little, answering in short, sporadic bursts. But each breathless whisper lands with a thud. When asked why she didn’t have an affair with the gallerist Leo Castelli, a close confidant, she quipped, “If you’re so friendly with someone, then you can’t go to bed with him.”

One exception was the painter Willem de Kooning, Marisol’s longtime peer. “I was hero-worshipping him,” she admitted. De Kooning was handsome and electric, but the tryst was short-lived. “He had about three women at the same time.” Marisol was devastated. But when the affair ended, after three months, she had no illusions: “When something is over, it’s over.”

She had no shortage of admirers. Nicknamed the “Latin Garbo,” Marisol was a knockout. In 1962, she was named one of Life magazine’s “Red-Hot Hundred.” Slender and doe-eyed, she was the darling of the art world. In pictures, she peeks out from behind her work, her gaze tantalizing. At a party in New York City, the artist Jackson Pollock put his face through a window, then tried to kiss her. He was splattered with blood, Marisol recalled, “like his painting.”

Andy Warhol, too, was spellbound. He included Marisol in a handful of his short films, each a glimpse of the demure, flush-faced artist. In one, Marisol looks this way and that, bathed in blush-tinged light, the faintest of smiles breaking through. She was coquettish, drawing people in slowly, unawares.

Thousands lined up to see Marisol’s shows. Her pictures ran in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. She was a star, by any measure. “In a town where either talent or a beautiful face are cachet enough,” Gloria Steinem wrote in 1964, “Marisol has both.”

The attention made her uneasy. After a celebrated show at the Castelli gallery in 1957, Marisol fled to Rome: “I had to reject something in order to be a strong person, even to be myself.” As her popularity surged, her sense of self receded. In 1960, she traced her figure “out of fear of losing my body and my mind.” She was everywhere and nowhere: “You have a million faces.”

Marisol was a chameleon: adept at inhabiting every part but her own. All the while, she strained for something to anchor her, something illusory: “I know I’ll never find it.”

What she found was a delight in the unknown. In 1968, Marisol escaped to Tahiti, where she took up scuba diving, spending a combined eight months out of four years underwater. Her sculpture from the sojourn, on view in the show, is luscious, of needle- and parrotfish, all fluid, sensuous lines. Projected alongside is Marisol’s own footage from her excursions, a profusion of turquoise, flecked with jade greens and lapis blues.

Above water, things were more complicated. The soirees grew longer. The attention smothering. Consider The Party, where a guest glitters in a gray sheath, patterned with interlocking rosettes. Another in billowing blue satin. Dotted throughout are sapphires, rubies, and emeralds, set in gold. But something is amiss. No one is speaking. The figures are dolls, each face a replica of the one before. The effect is nightmarish: a scene without end.

Marisol retreated into her work. In her studio, piled high with flotsam—discarded chairs and drawers, stove pots and bits of a baby carriage (Marisol often rooted through construction sites for material)—she toiled until the early hours of the morning. “I don’t lounge around,” she asserted, in 1989. “I’m either working or sleeping.”

Her diet, of ham and eggs, was more regimented than pleasurable. “Food doesn’t concern her,” Steinem noted. Take Dinner Date, in which Marisol shares a meal with herself. Seated unnaturally straight, the two women are uncomfortable, their TV dinners untouched. One, clad in a mustard-yellow dress, clutches a fork with a disembodied hand. Listless, the woman stares out, trapped in a stilted conversation.

“Marisol invented a way of looking at cliché, women, sexuality,” Chaffee contends. She places her figures in stuffy parties and interminable meals. She empathized with the ill-at-ease guest because it’s a role she played with aplomb.

Her playfulness comes through in Tea for Three. Awash in vibrant yellows, reds, and blues—a nod to the Venezuelan flag—is a stooge-like trio. Made up with rosy cheeks and scarlet lips, the figures are clownish, a minuscule house atop one’s head, another crowned with a finger-lined cap. Marisol was inventive, following her ideas wherever they led. “I have to spend three-four hours daily daydreaming,” she once said. “Otherwise I would lose touch with myself.”

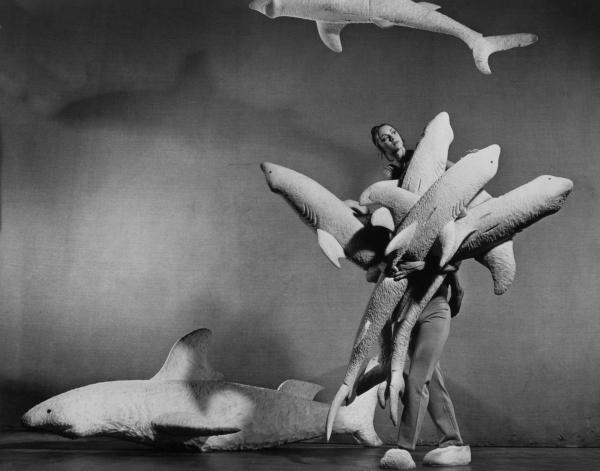

She never lost touch with her art. It was at its best, she told a reporter, when she gave herself over to it: “You have to forget your own being, to go into another consciousness, a kind of trance.” It was in that hypnotic state that Marisol made not only sculpture but landscapes on paper, streaked with fire-reds and sensuous limes. She designed costumes for shows like Louis Falco’s Caviar, on the life of the oceans, the dancers shimmering in Prussian blues and silvery greens.

In her off time, Marisol was restless. She sought out the peculiar, the strange, wherever she went. Arrayed on one wall in the show is a hand of garnet-red nails, a face encircled with fingers, and a bare foot atop a flesh-toned heel. It’s a snapshot of Marisol’s mind, flitting here and there, like a cat before an unspooled ribbon. (Marisol got rid of her own cats because they were always staring at her, “especially in the bathtub.”) She reveled in the disarray. “I like to have a lot of things around,” she maintained in a 1964 interview. It’s those curios that sparkle in the show, like blades of grass, dappled by sunlight.

Marisol moved through the world lightly. She took criticism in stride. When her sculpture of the beloved Belgian-born priest and missionary Father Damien was panned, she wasn’t fazed. One critic called it “the most barbarous thing,” another insisted that it be “removed or blown up,” and still another that it be buried “at the deepest depth of the ocean.” Marisol brushed it off. She wasn’t after celebrity, but the admiration of her peers: “If one artist you respect says he likes your work,” she explained, in 1965, “that’s the important thing.”

To sculpt with abandon, to be free, was foremost in her mind. Throughout her life, men told her they’d prefer a woman “who thinks about them all the time.” Marisol had other ideas. Her reasoning was simple: “I’m independent.” She wanted to see everything, to go everywhere. And she could only do that alone. “If you learn to live with yourself,” she pronounced, “you have achieved something.”

Marisol achieved much. But as far as she traveled, as deep as she swam, she remained as elusive as her art: stone-faced, flamboyant, and undeniably beautiful. “A work of art is like a dream,” Marisol declared, “where all the characters, no matter in what disguise, are part of the dreamer.”

In the slumber of her mind, Marisol could create, untethered. She could journey far, conjuring up glitzy parties and lackluster dinners, jokers and crimson nails. Unmasked, Marisol was as lively as any performer, suspended, enlivened, in the world of make-believe.

At a party, Marisol sat so still that a spider spun a web around her. When she got up, the guests were stunned. Marisol shrugged: “It’s happened before.”