In 1914, a reporter for Photoplay was sent to profile the film director Lois Weber. It was winter in California, and Weber was on the set of her latest picture, Hypocrites. The afternoon was scarlet and gold, according to the reporter, Lillian Hartman Johnson, peopled with a king and queen in fur-trimmed robes, white-clad monks, and scores of townspeople. As the actors took their positions, Johnson expected to hear the stirring of the crowd, the inevitable asides and giggles that delay a production. But, to her surprise, the cast and crew that day were eerily silent, “as though they were spirits.” Holding their attention, like a conductor’s baton, was the dark-haired, bright-eyed Weber, perched on a tree stump in a silk blouse, skirt, and tan boots. At Weber’s signal, the scene began.

“Lois Weber is an exception,” said director Cecil B. DeMille. “Most other women would crumple under the strain.”

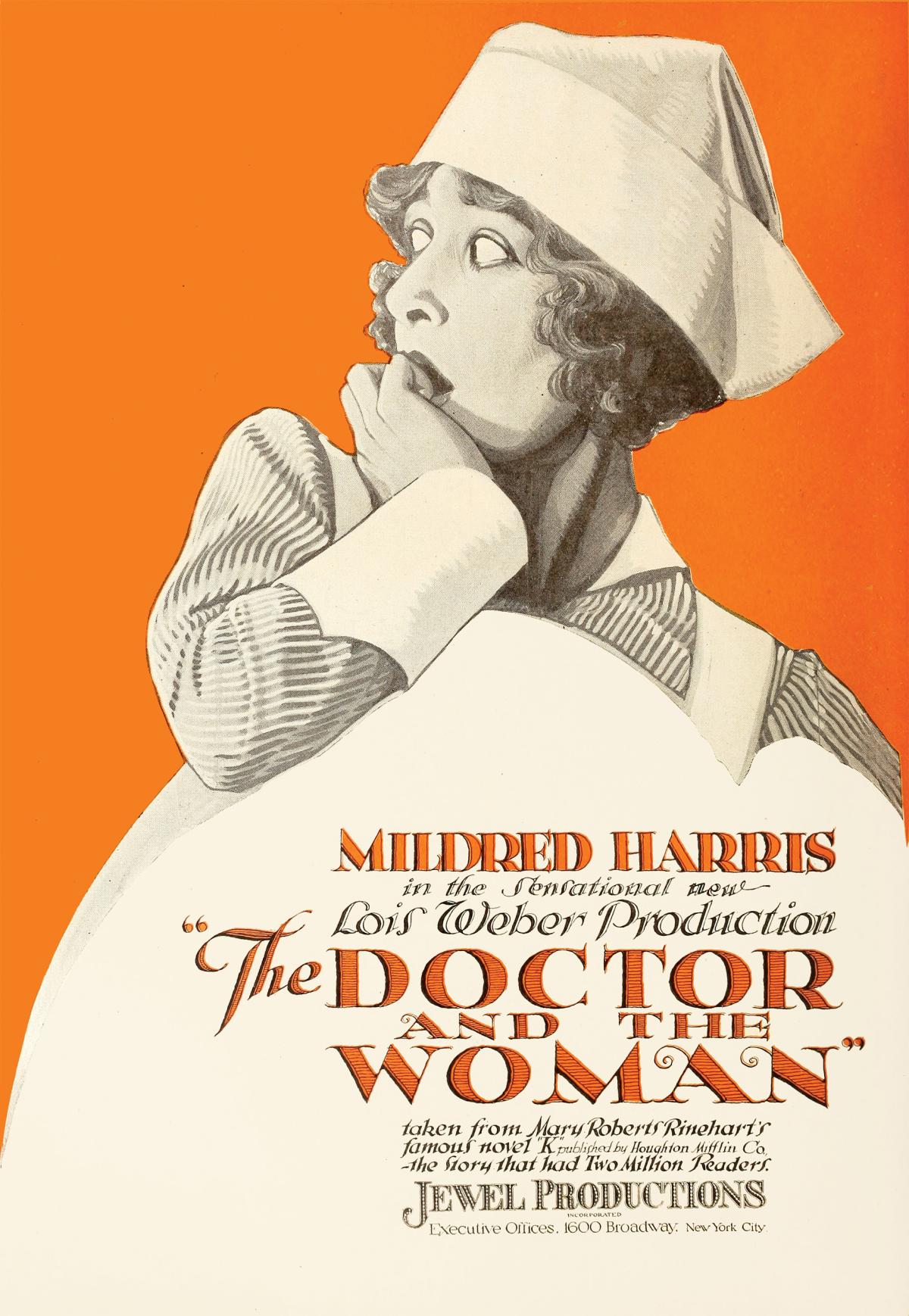

The first American woman to direct a feature film, Weber is credited with more than 40 features and 100 shorts. In 1916, she was the first woman to be inducted into the Motion Picture Directors’ Association. She struck while the iron was white hot: “Everybody was so busy learning their particular branch of a new industry,” she said, “that no one had time to notice whether or not a woman was gaining a foothold.”

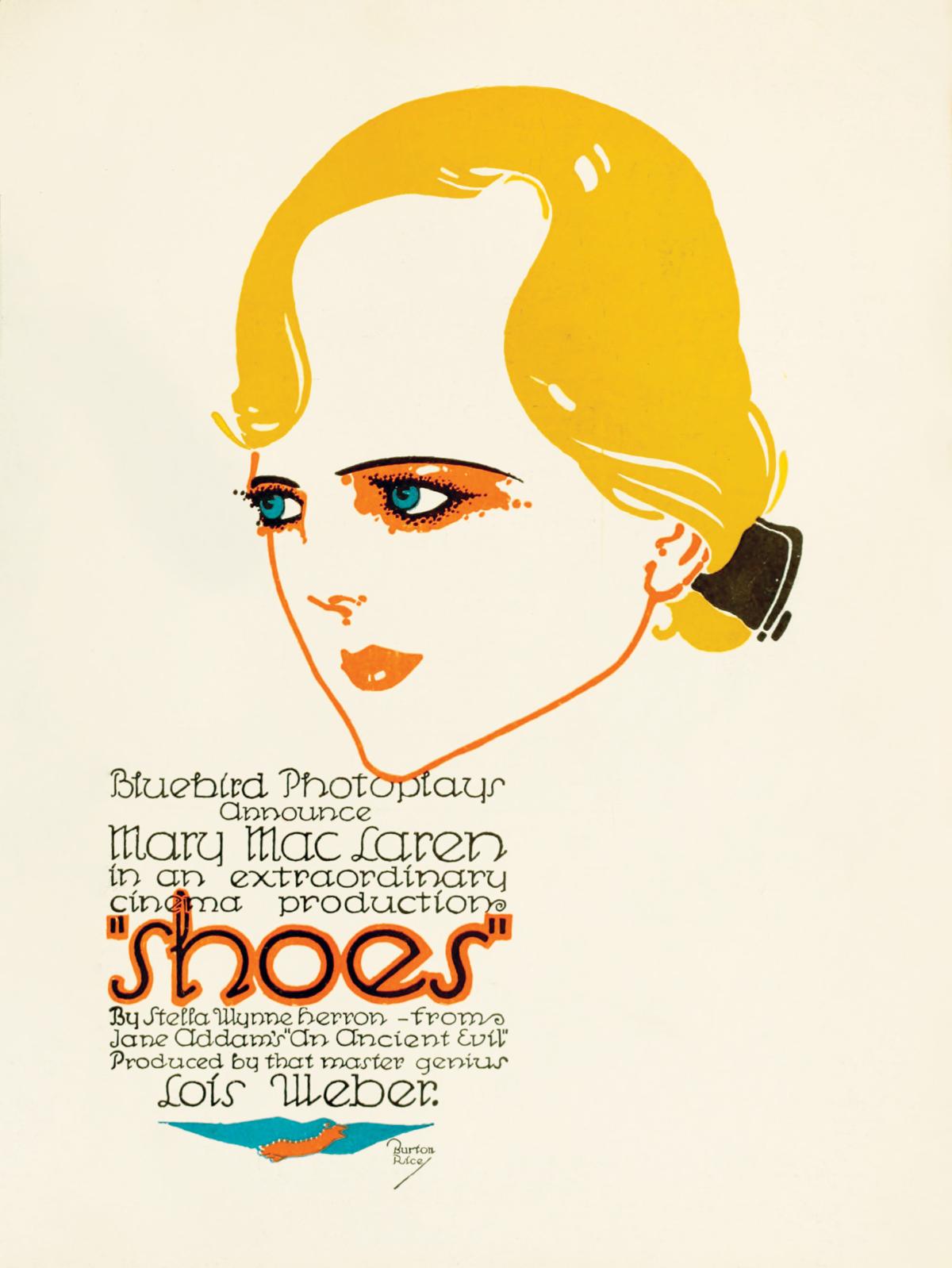

At a moment when directors DeMille and D. W. Griffith were captivating audiences with historical and Biblical epics, Weber was making pictures with interiority: at the edges, in the depths. Her stories, culled from experience, were of the here and now: a woman who keeps secrets from her husband, a shop girl who can’t afford a new pair of shoes.

For Weber, these portraits of urbanity, of life lived in mostly unpleasant company, were far from trivial. They were a kind of eternal truth. If films are to rival the novel and the theater, Weber told a reporter in 1917, they need to look at life’s contours, the “ideas which get under the skin . . . the things which endure.”

What endured, throughout Weber’s career, was a restless mind. Born in Allegheny City (now part of Pittsburgh), in 1879, Florence Lois Weber grew up listening to the stories dreamed up by her father, a decorator who worked on the Pittsburgh Opera House. By sixteen, she was a concert pianist, until a misstep rattled her: Weber was performing Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsody No. 8” at a concert in Charleston, South Carolina, when, overcome with fervor, she broke off one of the black keys. “I kept forgetting that the key was not there, and reaching for it,” Weber said. “The incident broke my nerve.” She never performed on a concert stage again.

Weber fared no better in New York City, where she moved in 1900. For a week, she recalled, “not a bite of food” passed her lips. Her hair fell out, “as if from some blight.” Brought low, Weber resolved to save herself and those around her. She returned to Pennsylvania when her father fell ill, never losing sight of a starry-eyed mission: to root out evil. “If you want to save souls,” her uncle told her, “who needs it more than chorus girls?” Convinced, Weber began singing with a tour group, soon earning the nickname “the Preacher,” so eager was she to correct, and convert, her fellow choristers. In her spare time, she sang with the Church Army, visiting the red-light district armed with a Bible, hymnal, and street organ. But, as she soon discovered, even saving souls has its limits: Her work with the Church Army, she confessed years later, “gave life a bitter taste for a while.”

Things sweetened a few years later when Weber joined a touring production of the play Why Girls Leave Home, where she met her future husband, actor Phillips Smalley. The two were married three months later. Weber spent the first two years of marriage on the road with Smalley and, “to keep my mind off the horror” of being apart from him, began to write scripts in hotel rooms. Her stories were picked up, first by Gaumont Talking Pictures, and soon Weber was not only writing but directing, inflecting her films with humanity: life as it is lived.

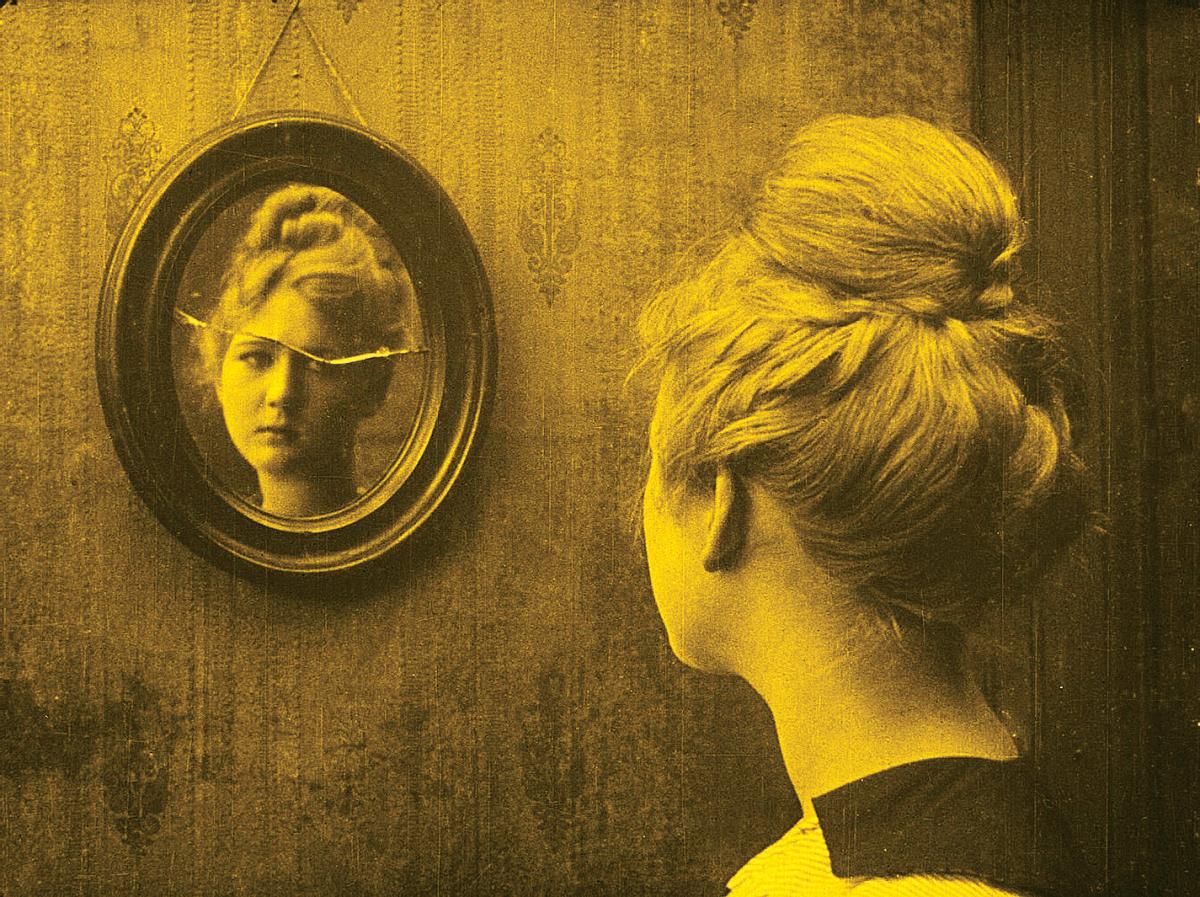

Nowhere was this more pronounced than in Hypocrites, the picture that made Weber an overnight sensation. Released in January 1915, a month before Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, Hypocrites was modeled after Adolphe Faugeron’s painting La Vérité, completed in Paris a year earlier. In the French canvas, Truth, depicted as a naked woman, stands in the darkened overhang of a rock bluff. She holds a torch before a dispersing crowd, its members clothed in dust blues, butter yellows, and pistachio greens, some shielding their eyes. In Weber’s film, a priest chisels Truth from stone and when she emerges—as a woman in a nude-toned leotard, superimposed on the underlying scene—she startles. (Boston’s mayor called Weber’s depiction of Truth “indecent and sacrilegious,” demanding that the actress be draped in a classical gown to “meet the requirements of the fastidious Bostonians.”) In the film, Truth flits back and forth, ducking behind birch trees. When she holds up her mirror, all are found out: the politician who takes bribes, the fiancé who cheats on his betrothed. What’s most unnerving about Weber’s picture is not evil masquerading as good but the idea that truth is coursing, furiously, through the world. Try as you might to conceal it, there it is, just across the way.

Weber, herself chiseling something from nothing, was an exacting presence on set. Ever compulsive, she rearranged headpieces and hammered poles in place, as if a puppet master, pulling one string, then another. Producer Carl Laemmle, with whom Weber worked at Universal, described her as “the only woman I have ever known who could work until two in the morning and be fresh and ready for another day’s work at six.” Weber’s ideas came to her in a flash or not at all. She was not inspired at her desk, of sumptuous mahogany, but as she paced about, a pencil and yellow pad of paper in hand. From her actors, Weber demanded clean slates. I prefer “mimics,” she told a reporter in 1916, “who take what I do and repeat it like children.” Her hand suffused every shot. When an actor had a “faulty profile,” Weber filmed him in full-face view, with one half cast in deep shadows to give the effect of an ideal profile. She had no time for flaws.

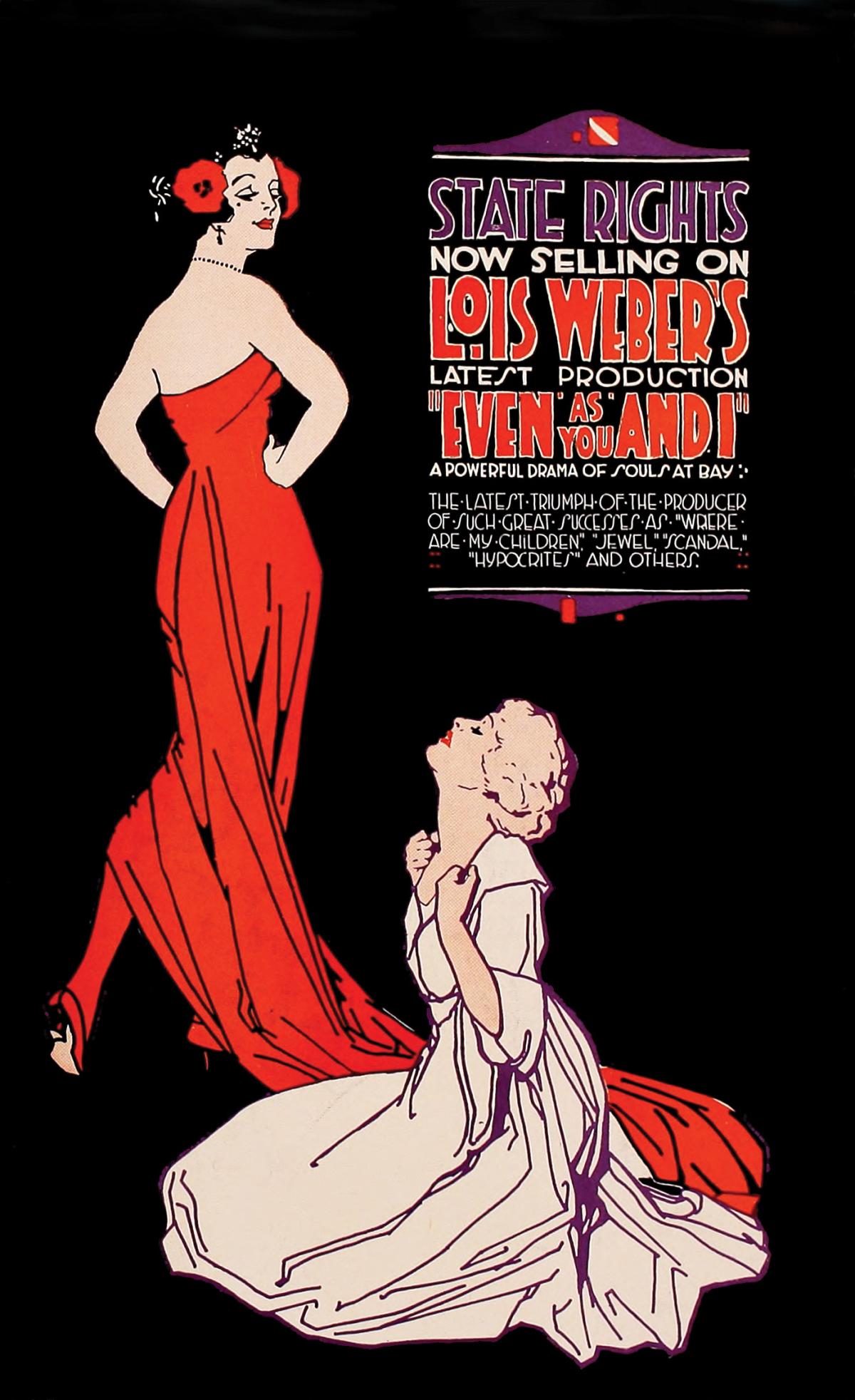

The hard-nosed Weber did not shy away from controversy. With her 1916 picture Where Are My Children?, she took up the subject of birth control. The film, pervaded by eugenics theory, namely that contraceptives are best suited to the working class, conflates birth control and abortion. But the heavy-handed picture—which a member of the Pennsylvania censorship board called “unspeakably vile” and a “mess of filth”—is not without pathos. In one scene, Edith, a well-to-do woman who does not want children, sees her husband staring lovingly at a baby. The couple’s eyes meet, then break away. In that moment, the two characters aren’t at odds. They are people who want different lives for themselves and see, in an instant, that the person they love is foreign to them. For a second, they are strangers.

That’s where Weber comes into her own: not in her social commentary but in her quiet moments, in the stillness. Shoes, also released in 1916, similarly sparkles in half-light. One such scene is midway through the film. Eva, a shopgirl whose leather boots are in tatters, is sitting on a park bench flooded with light. She is nearly invisible in a gray-black suit and wide-brimmed hat. A group of women glide by, the camera lingering on their high heels, each of rich leather and lush tonality. Eva is humiliated and, with her head hung low, hides her frayed boots under the bench, all the better to forget them.

Weber reveled in scenes like these: when rich and poor, good and evil, are forced into close quarters. To audiences, however, it smacked of moralizing. Weber had always viewed films as “the finest pulpit in the world,” but, with World War I raging, audiences didn’t need a sermon. They needed, as Weber put it in 1917, to forget. She started her own studio, set among rose bushes and shade trees. In her 2015 biography, historian Shelley Stamp elaborates on the turn in the director’s career: “Weber had pledged to abandon the ‘heavy dinners’ she made at Universal in favor of ‘little afternoon teas,’” trading films that instruct for pictures that delight. The studio eventually collapsed as a result of industry conglomeration, but, for four years, Weber had the freedom she’d long sought. Nearly a decade later Virginia Woolf would assert that if a female writer has a room to herself, “something of great importance has happened.” For Weber, that meant films that were lighter, more fluid, as if, freed from saving the world, she could finally live in it.

This newfound fluency comes through in her 1921 film Too Wise Wives. In one poignant scene, Marie, a loving but overbearing wife, is having breakfast with her husband. Seated in a luxuriant dining room overlooking a lavish garden, Marie is on edge. She checks and double checks the food—fried chicken, her husband’s favorite. She putters around, feverishly, selecting just the right piece of meat for her husband when he blurts out what we’ve all been thinking: “Suppose we stop fussing so much about what we eat, shall we?” Marie is frozen, as if something within her has shattered, her world, undone. Weber here is direct: Anything loved too dearly will vanish. If only Marie could be light, airy. Midway through the film, we see what she lacks. Marie is on a shopping trip with Sara, a bubbly socialite. After looking at a few frocks, Sara emerges from the dressing room in a sequin gown overlaid with satin, falling on either side of her skirt in handsome folds. More bird than woman, Sara dazzles. Marie, looking on from a nearby stool, sees for a moment the woman she could be, untethered.

For Weber, the ideal woman was sprightly, full of whimsy. In a 1921 interview she compared two wives: one, a “wilted rose,” who bids her husband good-bye and watches him from the door, “her heart in her eyes;” the other, a woman about town, who spends her days shopping and at the cinema. Wives should strive to be the latter, she concluded, “a jolly little pal, full of pleasantries.” Weber wanted women to be spry only insofar as it would please their husbands, who, she contended, only wanted to be “let alone and . . . amused,” but her underlying conviction was sure: Women, however adoring, need time to themselves. Weber elaborates on the theme in her 1927 picture Sensation Seekers. In one scene, a beautiful partygoer asks a reverend if he thinks the “modern girl” is going to hell, to which he replies, “No, but it is disconcerting to watch the young woman of today grow into—manhood.” At this, the two erupt into laughter. Here the question of what a woman should be is a moot one, or, at the very least, too stuffy for filmgoers.

Offscreen, life was more complicated. Weber filed for divorce in 1922, citing Smalley’s “habitual intemperance,” and, a year later, she suffered a mental breakdown. One journalist observed, her “windows were closed, curtains closely drawn. No ring at the door was answered.” Weber returned to the director’s chair in early 1926, but the industry was changing. By the end of the decade, talking pictures were in vogue, and she was passed up for new filmmakers. “Weber was effectively written out of history,” Stamp notes, “at the same moment she was written in.” Still, Weber continued to direct films until five years before she died, in November 1939, of a chronic stomach ulcer.

Almost every writer who interviewed Weber mentions her eyes. Some write that they were a beautiful blue, others green and turned up at the corners, still others violet. Whatever their hue, they were captivating. Weber charmed, even as she corrected. A reporter visiting Universal, in 1914, found Weber going through miles of snake-like film, as she often did until midnight, as though unraveling knot after knot. On set, she was a self-described “mad thing,” grasping at a vision, a vapor, that only she could see. Directing, she wrote in 1915, requires an “infinite capacity for detail; an apparent sixth sense.” Weber had that instinct and no patience for those who didn’t. If the artist’s message is true, Weber pronounced, “the world grows to him.” Her mind was quick, panther-like: to sit still was to fail.

A group of film magnates were debating who should hold the title of best director, Weber recalled, in 1928. “A half dozen best ‘men’ had been named,” when producer Carl Laemmle said, “Well, gentlemen, my best man is a woman.”