Health care has been a topic of interest at NEH since at least 1974, when the agency awarded an education grant to support a humanities studies program for premed students at the University of Florida.

And anyone who attended this year’s Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, or watched it online, learned how Rita Charon, a professor of medicine at Columbia University, has spent the better part of her career looking to import the benefits of literature study into clinical practice. Even before NEH supported Dr. Charon’s work, however, it became involved in another extraordinary project, known as Literature and Medicine, which began at the Maine Humanities Council in 1997.

There started a unique book club for doctors, nurses, and just about anyone else working in a hospital. It was a way to prod science-oriented professionals to speak about themselves through characters found in fiction, poetry, and drama. Not the sort of thing folks in lab coats tend to discuss at the watercooler.

More than two decades later, what began with grants from NEH as “Literature and Medicine” in the far reaches of New England has been adopted in 26 states. Maine’s program now extends to those who work with victims of domestic violence as well as military veterans and the general public under the title, “Literature and Public Life.”

Social issues are often easier to discuss through a work of art than graphs and charts, says Elizabeth B. Sinclair, who pioneered the program for Maine Humanities and continues to oversee it 21 years later. “We feel like we’re doing something special for professionals in high burnout fields.”

In April 2017, NEH awarded Maine Humanities $200,000 to fund “Literature and Public Life” for three years. Anderson says upcoming topics include health care, education, end-of-life issues, and domestic violence. In addition to literature, film will also be used to prompt conversation. Future discussion groups may include those in law enforcement, another example, says Anderson, “of workplaces engaged in the public good.”

For the past dozen years, Hemingway scholar and retired Williams College professor Susan Beegel has led these book discussions for Maine Humanities, placing her PhD in literature aside when she enters a library or domestic violence prevention center.

“It’s not our job to be scholarly or teach,” says Beegel. “We’re there to make it easier for people to open up.”

The books selected for the program sometimes address a problem directly, such as The First Thing and the Last, a 2010 novel by Allan G. Johnson, which opens with a suburban woman’s horrific beating at the hands of her husband.

Other works, like the Tennessee Williams play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, have been presented as dramatic readings by theater groups, bringing the issue of family violence within a more layered drama to caseworkers.

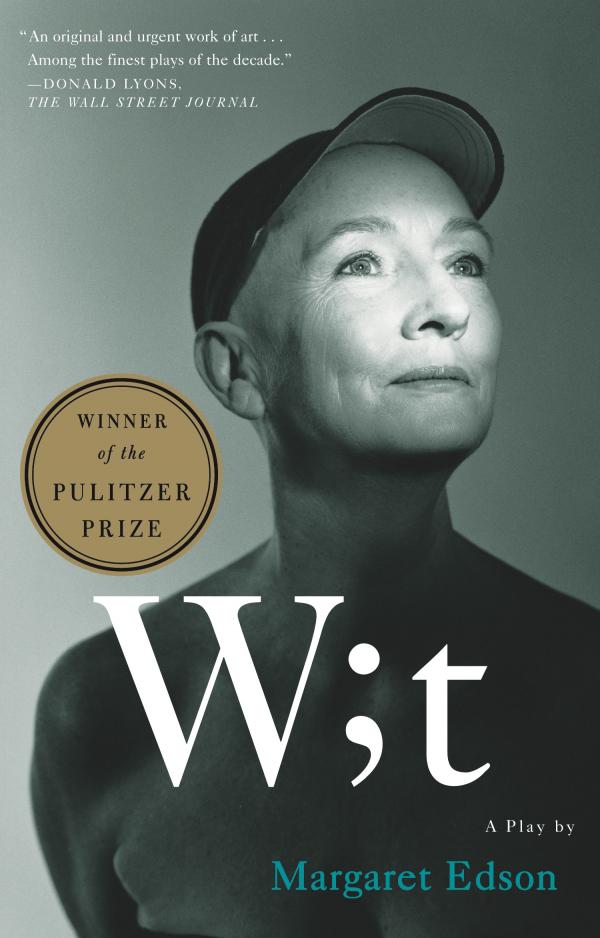

And the Pulitzer Prize-winning drama from 1999—Wit by Margaret Edson—seems to have changed the way many doctors interact with patients, according to Beegel.

A neurosurgeon attended a “Literature and Medicine” discussion of Edson’s story about a professor of English reflecting on her life while dying from ovarian cancer. Beegel says the surgeon returned to the group and described how the play had persuaded him to spend more time with his terminal patients, despite pervasive business guidelines that limit the time doctors should spend with patients.

“Literature and Medicine” works in different ways across the country, says Hayden Anderson, executive director of the Maine council. “We’re no longer the clearing house” for establishing the program out-of-state.

The program has been in place at Mercy Medical Center in Maryland since 2004, established after a hospital administrator traveled to Maine to see it in action. The Baltimore-based hospital’s version of “Literature and Medicine” gathers up to 25 people to discuss literature once a month for five months each year.

One virtue of the program, says Mercy spokesman Dan Collins, is that “people check their titles at the door.” So, he was just Dan, son of Walter, when the group discussed a poem written by his father in tribute to his wife, who died of Alzheimer’s in 2001.

Other works used over the years at Mercy include The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, an account by Anne Fadiman of a Laotian Hmong family resettled in Merced, California. The book documents the clash of an Old World culture dependent on folk remedies and Western medicine in treating the family’s daughter for epilepsy.

“The reading material is the catalyst for people to share their experiences in medicine” or their private lives, says Carole Rybicki, a Sister of Saint Francis and a Mercy chaplain. “The response you get can be as basic as ‘I agree or disagree’ with the text, to ways to better handle situations the author describes.”

While the program often influences how participants do their jobs—the primary objective—it doesn’t always result in a sustained love of literature.

“I wish I could say it did,” says participant Melody Fitch, executive director of Maine’s Family Violence Project, headquartered in Augusta. “I work long days and my down time is usually enjoying the outdoors.”

But that, said Fitch, “is why we treasure the opportunity” to be a part of the discussion.