Replete with luminous oils, undulating sculptures, and richly woven tapestry, “Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche,” which recently ended a three-museum tour across the Southwest, traversed five hundred years of history. At its center was a single Indigenous girl whose life story has been revisited and reinterpreted over the centuries: La Malinche, a figure at once beloved and reviled and about whom little is certain except that her legacy will remain fraught for a long time to come.

“She had no people,” Victoria I. Lyall and Jesse Laird Ortega write in the exhibition catalog. Lyall, who co-curated the show with Terezita Romo and Matthew H. Robb, stresses that Malinche was, from the first, alone in the world.

Born in 1501 in Paynala on the Gulf of Mexico, Malinche lost her father while still a child. Her mother remarried and, eager to secure an inheritance for her new son, sold Malinche into slavery. That is one version of the story. More likely, Malinche was taken from her family as a girl, then sold to the Mayas, who gave her and 19 other women to the Spanish.

Laura Esquivel, in her novel Malinche, imagined the moment when the girl of five was separated from her mother: “[Malinche], with her things on her back, clung to her mother’s hand as if she wanted to become one with it.” Then the inevitable occurred: “Her mother let go of her tiny grasping fingers, gave her away to her new masters, and turned away.”

In a photograph small enough to escape one’s notice, artist Delilah Montoya presents Malinche as a girl adrift. Dressed in a white, lace-lined communion dress, she is more doll than human. Clutching a rosary, she stands before a curtain that only partly obscures the brothel behind it. The effect is chilling. Malinche is solemn, rigid, as one might be before bursting into tears.

Passed off “from hand to hand, night to night, denied and desecrated,” Lucha Corpi tells us in one of the catalog’s absorbing poems, Malinche was “waiting for the dawn . . . that would never come.”

What came instead was a way of understanding her captors. While enslaved, Malinche added Maya to her native Nahuatl. And when she was given to the Spaniards, in 1519, her fluency caught the attention of Hernán Cortés, who promised Malinche “more than liberty” and made her his interpreter, first alongside friar Jerónimo de Aguilar and then solo when she learned Spanish. Malinche bore Cortés a son, Martín, mythologized as one of the first mestizos, or people of mixed Indigenous and Spanish heritage.

This adept—or, rather, dutiful—Malinche is vividly shown in the final chapter of the Florentine Codex, an encyclopedia of Nahua history dating to 1577. The codex presents Malinche in conversation with an Indigenous man, Cortés looking on. Pictured at the center of the discussion, one of many exchanges that would shape the future of her community, Malinche is not just translating: She is making history.

This characterization was echoed in an expansive canvas across the way, The Baptism of the Lords of Tlaxcala, one of the show’s largest works at ten feet tall. Tucked behind Cortés in an elaborate rite of passage, Malinche looks out with a wistful remove, as if she sees something the viewer cannot.

More than a linguist, Malinche was an interpreter, and it set her apart. “This was a universe where people spoke many languages,” Lyall explains, “but Malinche had an ability to leverage that skill.” At a seminal moment in the history of the nation, “she understood the bigger picture.”

One of the show’s oil-slick bronzes evoked this quality of knowing. Set before an emerald-colored wall, Malinche, in sculptor Emanuel Martinez’s hands, is lithe, an eagle atop her head and gossamer-like feathers enveloping her. Like Antaeus, who drew his strength from his mother, the earth, Malinche is in a kind of gestational phase, attuned to the land below her feet. The novelist Ireneo Paz reflects on Malinche’s gift: “It was enough that she saw some facial lines, the movements of the mouth, the expression of the eyes, so that right away she was in possession of the whole situation.”

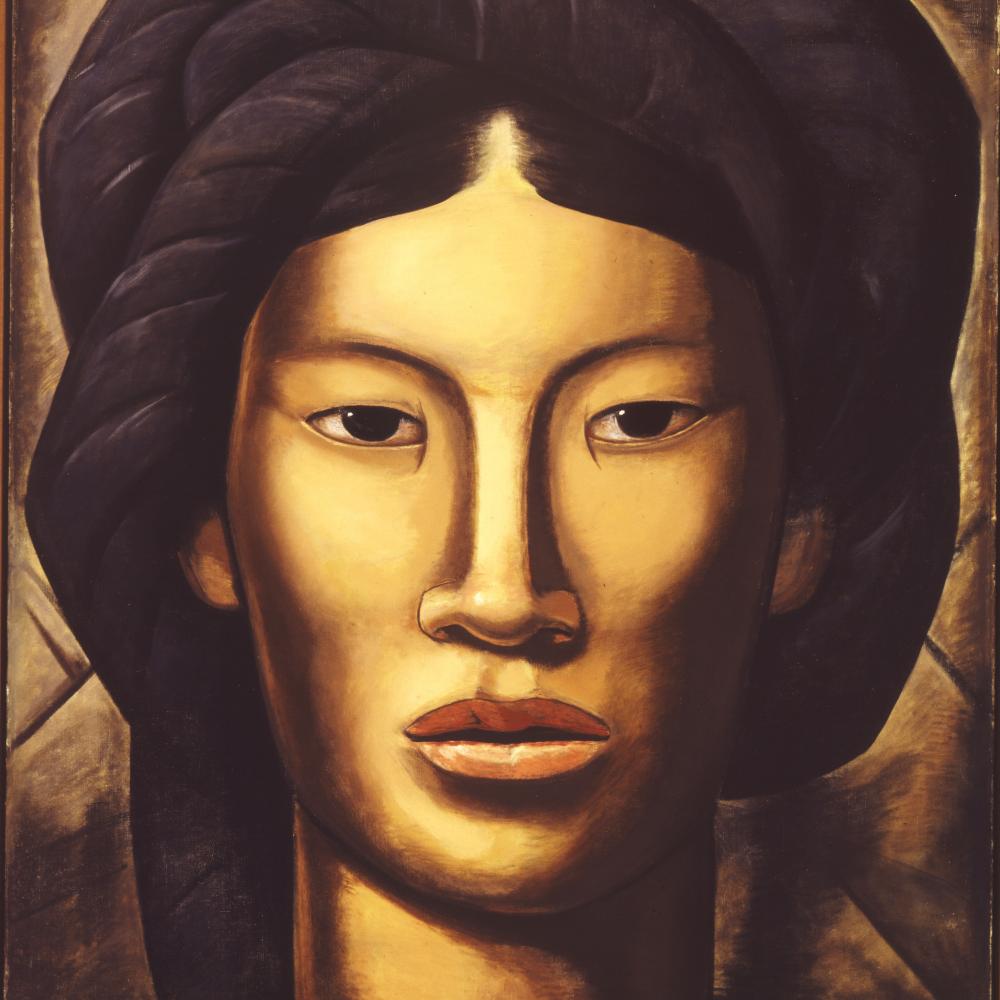

Alfredo Ramos Martínez’s incandescent portrait has a similar air. Crowned with braids on a spare canvas, Malinche meets the viewer’s gaze directly. Nothing, it seems, can escape her piercing, raven-black eyes. Curator Romo emphasizes that it is difficult to place this Malinche. She looks Indigenous, but it is unclear where, precisely, she is from. That ambiguity is just the point: Malinche’s exact village matters little. Instead, she is Indigenous through and through, and that, Romo continues, is “a source of dignity, pride, and beauty.”

This self-possessed Malinche became a target in the nineteenth century: “When Mexico gets its independence from Spain,” Romo says, a feeling of resentment sets in. “There is a reaction against everything Spanish.” Malinche, Cortés’s interpreter and mother to his firstborn son, came under fire. This spirit carried over to the post-revolutionary era, when José Clemente Orozco painted, in 1926, a mural of Cortés and Malinche, one that was reproduced in the exhibition, casting a disconcerting pall over the show. In the grand composition, Malinche and Cortés are pictured as Adam and Eve, sitting side by side, a lifeless Indigenous man at their feet. Cortés holds Malinche back, her downward glance haunting. On the opposite wall, in the gallery’s La Traidora section, Malinche was a fiery Carmen in a surrealist bullfight. The work is ablaze with fanciful hues, a jagged red flourish standing in for a bull. Like Carmen, this Malinche is a temptress and will no doubt meet a tragic end.

Jesús Helguera’s lush canvas is imbued with a similar exoticism. The vast 1941 work, dominating its own wall, was hung on the far side of the open exhibition space, beckoning. In the florid composition, Malinche and Cortés ride on horseback in a densely wooded forest, a band of soldiers following closely behind. Rupturing purples, sea greens, and electric blues permeate the canvas. Malinche, set against the armored Cortés and his blood-red cape, is languid in a traditional white dress, one hand gesturing to the crucifix around her neck, the other drawing up the fluttering hem of her shawl.

It was this luscious Malinche that writer Octavio Paz, Ireneo’s grandson, took aim at in his 1950 book-length essay Labyrinth of Solitude. Titled “The Sons of Malinche,” the fourth chapter dismisses the interpreter as “violated” and “seduced by the Spaniards.” The disgust was palpable: “As a small boy will not forgive his mother if she abandons him to search for her father, the Mexican people have not forgiven La Malinche for her betrayal.” At root in Paz’s condemnation, Romo remarks, is resentment of a new order: “He looks on Malinche as someone who willingly seduced Cortés or gave herself freely to him. This leads to a shame that is passed on through generations, perpetuating a solitude and self-isolation.”

But Paz’s essay was not the last word on the subject. Later poets, writers, and artists, many of them Chicana, reimagined Malinche as a resilient woman caught in a dilemma not of her own making.

“We will never know [Malinche’s] story from her point of view,” says Lucía Abramovich Sánchez, who curated the San Antonio Museum of Art show. What is clear is her unfailing resolve: “She did what she could to survive.”

Malinche’s strength of character became a focal point as new generations identified with her power and her plight. Scholar Adelaida R. Del Castillo puts it elegantly: “If there is shame for her, there is shame for us.” The artist Carmen Lomas Garza proclaims, “We are all Malinches.” Alfredo Arreguín’s painting Malinche (with Tlaloc), one of the show’s wildest, reverberates with this spirit. In the vertiginous canvas, Malinche is pictured under a dizzying array of Indigenous prints, her face the only anchor in a delirium of pattern. The effect is ecstatic but never clamorous, inviting the viewer to revel in Malinche, a woman tied to her Indigenous roots and yet standing apart from them. As the Malinche character in Rodolfo Usigli’s 1960 play Corona de Fuego remarks, “the same blood that joins us sets us afire.”

What came through in the exhibition’s final room was Malinche, the woman. As Lyall and Ortega remark in the catalog, Malinche is rarely portrayed alone in her earliest depictions: At times, she is at the center of a crowd, at others, she is Cortés’s shadow. By the show’s end, Malinche was not an idea or a myth but a person.

The show closed with Malinche pictured as an aging woman, one of her braids neatly lopped off. She looks out with raw detachment: a woman we do not recognize but have seen before, one, like a face spotted from a closing train door, near but unreachable. In the work, artist Gloria Osuna Pérez gestures to her grandmother, who finally let her daughter cut her hair, which she could no longer maintain. Pérez recalls: “She had lost control of her world and died shortly afterwards.” Titled La Malinche, the work imagines Cortés’s interpreter as the old woman she never became, having died, in all likelihood, at thirty. Like so much of the show, this procession of contrary ideas, all relating to the same person, cannot be parsed logically. You can only surrender to it, letting the work overtake you.

Contradictions were a major concern of Gloria Anzaldúa’s 1987 book Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. According to Anzaldúa, at the intersection of Indigenous, Mexican, and Anglo culture is a hybrid figure: a new mestiza. Situated between cultures, the mestiza embraces the oppressor and the oppressed: “At some point, on our way to a new consciousness, we will have to leave the opposite bank, the split between two mortal combatants somehow healed so that we are on both shores at once and, at once, see through serpent and eagle eyes.”

Pre-Columbian symbols of Mexican identity, the serpent and the eagle are bound up in the new mestiza, who, Anzaldúa argued, can navigate the world, darting by and arriving, in the end, unscathed: “We are the people who leap in the dark, we are the people on the knees of the gods. In our very flesh, (r)evolution works out the clash of cultures. It makes us crazy constantly, but if the center holds, we’ve made some kind of evolutionary step forward.”

Malinche takes that step. She is torn between cultures and belongs, in the end, to everyone and no one at all. “She was not Aztec, not Maya, not ‘Indian,’” historian Frances Karttunen asserts. She is “nobody’s woman.” Yet there is something about Malinche that transfixes us. Her guarded smile, perhaps, or her steady gaze. Lost to us are the details of her life: what she endured, what she dreamed. But walking through the galleries, a sense of her perspective emerged. As Carmen Tafolla’s poem “La Malinche” puts it, “I saw our world / and your world / and another.”