When I was seventeen, I traveled from Buenos Aires to the north of Argentina to partake in a three-day feminist congress in the city of Salta, a town known for its notable abidance to the Catholic religion and its hostility to feminism. The congress culminated in a massive march through the center of town, where we were exposed to giant crucifixes, holy water dripping on us, and, eventually, tear gas from the police.

In the midst of this chaos, I remember women were singing a song about the Mirabal sisters. I’ve forgotten the chant, but I remember lyrics that pay homage to the Dominican sisters’ political bravado—how, even at the height of the dictatorship led by Rafael Trujillo, they defied the expectations of a repressive society (like Salta itself) and became militant rebels until their cowardly murders in 1960.

That was before feminism was a massive movement throughout Latin America, before abortion was legal in Argentina, and before these ideas became coopted by wider media and pop culture narratives. I knew about the case of the Mirabal sisters from a passage in Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Feast of the Goat. But I didn’t know that, before Vargas Llosa, there was Julia Álvarez—a Dominican American writer who told the stories of the Mirabal sisters broadly, intimately, and for the first time, shedding light on their personal lives as well as on their tragic political history, with humanity and pathos. Álvarez’s 1994 English-language book, In the Time of the Butterflies, became a sensation and was soon made into a movie, starring Salma Hayek and recasting Álvarez’s incredible prose for the big screen. A new documentary, Julia Álvarez: A Life Reimagined, retells this and many other fascinating episodes of the writer’s life, in the first-ever film about her remarkable trajectory, work, activism, and cultural production.

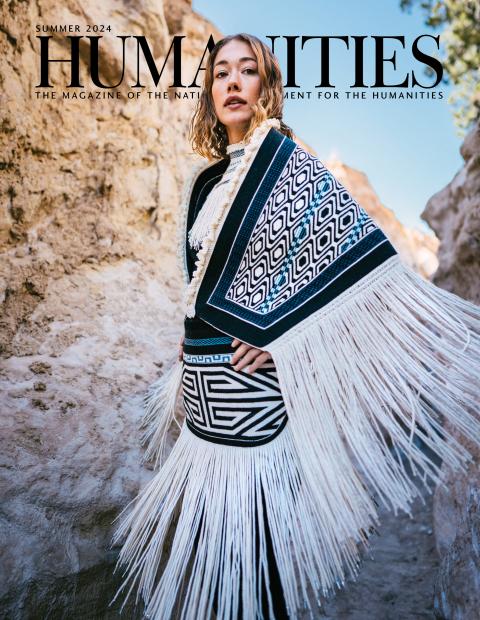

The documentary opens with Álvarez’s voice which, parsimoniously and eloquently, tells us about her labor of love as one of the main Latin American writers of her generation (perhaps the most important of her time in the English-speaking language). Wearing red and black garments and a butterfly necklace (a respectful nod to the Mirabal sisters, whom she popularized as the mariposas, or “butterflies”), she says:

My string in the labyrinth of my life has always been the storyline, has always been the writing. When we came to the United States, we left everything behind, even our language, our cultures, our families. But I carried the portable world of the imagination, and that’s where I landed: I landed in that place of story. And so that’s the place that I move and think and feel in the worlds that I create.

This statement, which serves as a poetic opening for A Life Reimagined, could also be a key for understanding her oeuvre as a whole. For, indeed, Álvarez made a career not only of telling stories, but of relaying a specific experience of immigration, made both in the nostalgia for the past and the hopefulness for the future—as if creating bridges between two lives lived, two languages, and two cities.

Although born in New York City, Álvarez spent her early childhood in Santo Domingo. She was raised with three sisters (Maury, Tita, and Ana) by her father, Eduardo, a doctor of humble origins, and her mother, a housemaker named Julia from the country’s haute bourgeoisie. During the darkest years of the Trujillo dictatorship, Eduardo became an incognito member of the resistance. When the Álvarez sisters were children, Julia’s sister Ana remembers that her father would hold secret meetings with other rebels in their house, and he was both “in touch with Cuba and with the CIA . . . whichever one helps [him] first.” When the situation became too claustrophobic and repressive, months before the murder of the Mirabal sisters, the family fled in a nerve-wracking plane ride and landed in the United States.

It was within the United States that “the place of story” that Álvarez so warmly remembers in A Life Reimagined started to fully gestate—in this case, as an exophonic writer (i.e., a writer producing literature in a language that, strictly, was not her own). She and her sisters describe her childhood in a white neighborhood in Queens as relatively hard, being singled out as the outcast, nonwhite family. While Álvarez attended the prestigious Abbot Academy in Massachusetts, where she learned the canon of English-language poets, her prose remained distinctly attached to her Latin American origins. In the documentary, she says: “I was trying to sound important . . . [like] a viable American writer. But I had my Latina cadences and my stories—my tías were not ‘aunts.’ I couldn’t translate it.” It wasn’t until Álvarez fully embraced her untranslatability, her fate of bilingualism, that she started penning short stories and poetry that would become hugely successful in the mainstream.

The product of this unique intersection between a high and low register was a sensation, especially as she published her debut novel How the García Girls Lost Their Accents in 1991. Written in a way that makes one feel at the center of a very loud, very fun dinner party, this vaguely autobiographical novel portrays the lives of four Dominican sisters that flee Trujillo’s dictatorship and find a new home in the United States. It does so kaleidoscopically, in a modernist, and often bilingual, narrative that shifts between perspectives, voices and styles, and which begins with the grown García sisters as they go back in time, descending chronologically back into their origins. While the novel’s relevance has been well established (it is the precursor of many contemporary forms of immigrant writing from Latin America, from Junot Díaz to Elizabeth Acevedo and onward), the documentary provides Álvarez’s readers with a more textured context of her life while writing How the García Girls Lost Their Accents, which was well received by the public and poorly received in her household. “Mami was embarrassed that her daughters knew about sex, drugs, boyfriends,” Álvarez says in the film. “They slept with people before they were married. . . . I kept saying, Mami, it’s fiction. I made this stuff up . . . a lot of it was also made up. But she was afraid that it reflected on her.”

Although Álvarez’s sisters were furious and her mother refused to speak to her for years after her debut novel came out, she kept on writing. One of the most interesting claims that the documentary makes is that a writer’s life is made through discipline, as opposed to romantic ideals of inspiration. Álvarez writes every day, the documentary tells us, with the diligence of a Cossack soldier and the focus of a chess player. After García Girls, she moved on from fictionalizing her experiences to political fiction, especially as she interviewed the now-late Dedé Mirabal in the early nineties, the only sister in the Mirabal family who survived the brutal assassination. Dedé provided her with access to the personal family archive, telling her stories and describing the family life that preceded the murder of most of her clan. “A novel is the truth according to character,” says Álvarez in the film. She exercises this principle when she travels to the Dominican Republic and struggles to fictionalize the three Mirabal sisters, providing their tragic lives with nuance and emotional depth. She found inspiration in the memoirs of rebels during the Nazi occupation in France and the life of Benazir Bhutto, the first woman elected as Pakistani prime minister.

In the Time of the Butterflies was a very different kind of book, both in form and in its personal significance for Álvarez’s life. “García Girls,” she says, “was about the generation that left, more modeled on my sisters and myself. In the Time of the Butterflies was an effort to understand what they call . . . in this country, the generation that was traumatized because they were raised in the dictatorship. And that novel helped me understand the baggage, the baggage that my parents carried when they went to the States.” This sophomore novel, which had a massive success in the United States as well as abroad, created sutures in her personal life, too: After many years of not talking, her mother finally came back into Álvarez’s life in light of the success of In the Time of the Butterflies. Inspired by the struggle of the Mirabal sisters, which Álvarez popularized responsibly in her account, her mother reentered her life and became a United States ambassador for the rights of women. Shortly thereafter, Álvarez’s mother and the Dominican mission introduced a draft resolution to the United Nations designating November 25th, the day of the Mirabal sisters’ assassination, as the international day for the elimination of violence against women.

The remainder of Álvarez’s career would be spent alternating between political activism and fiction, sometimes overlapping both. Later in life, she wrote about wide-ranging topics, most recently about grief in the 2020 best-selling novel Afterlife. Álvarez also became acquainted with the struggles of farmers in the Dominican Republic when faced with agricultural corporations and, far from merely witnessing or writing about their miseries, Álvarez and her husband started a farm of their own to oppose the advancement of large-scale farming. The farm was later donated to the Mariposa Foundation, an organization named after the Mirabal sisters that promotes the advancement of young women, where Álvarez herself volunteers. And, because it couldn’t be any other way, Álvarez accompanied her mission of literacy with her own fictional production—penning bilingual children’s books that touch cleverly on immigration, the Trujillo dictatorship, and grief.

Julia Álvarez: A Life Reimagined is the beautifully told symphony of the author’s life. Like any good symphony, which zooms into the virtuosity of each musician and instrument, it shows the strength and beauty of all the parts of Álvarez’s remarkable career—from her vocation to write and teach fiction, to her political activism, to the warmth and depth of her family life and the experiences of a life spent between New York City and Santo Domingo, and between Spanish and English. In the end, we have the portrait of a writer who was able to pioneer a specific type of literature that speaks to two traditions in their entirety, without losing anything in the process, building bridges between one language and the next.