I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. —Invisible Man

In the summer of 1945, Ralph Ellison, an Oklahoma-born, Harlem-based writer, wrote those words in Waitsfield, Vermont. World War II was ending, and Ellison was on sick leave from his duties as a merchant mariner. He originally came to Vermont to write a war novel with a racial twist involving white and Black Americans in a German POW camp. But, from his own account, those words about invisibility traveled from the innermost region of his mind to paper. Seven years later, in 1952, those words formed the opening sentences of the prologue of Invisible Man, Ellison’s first and only novel.

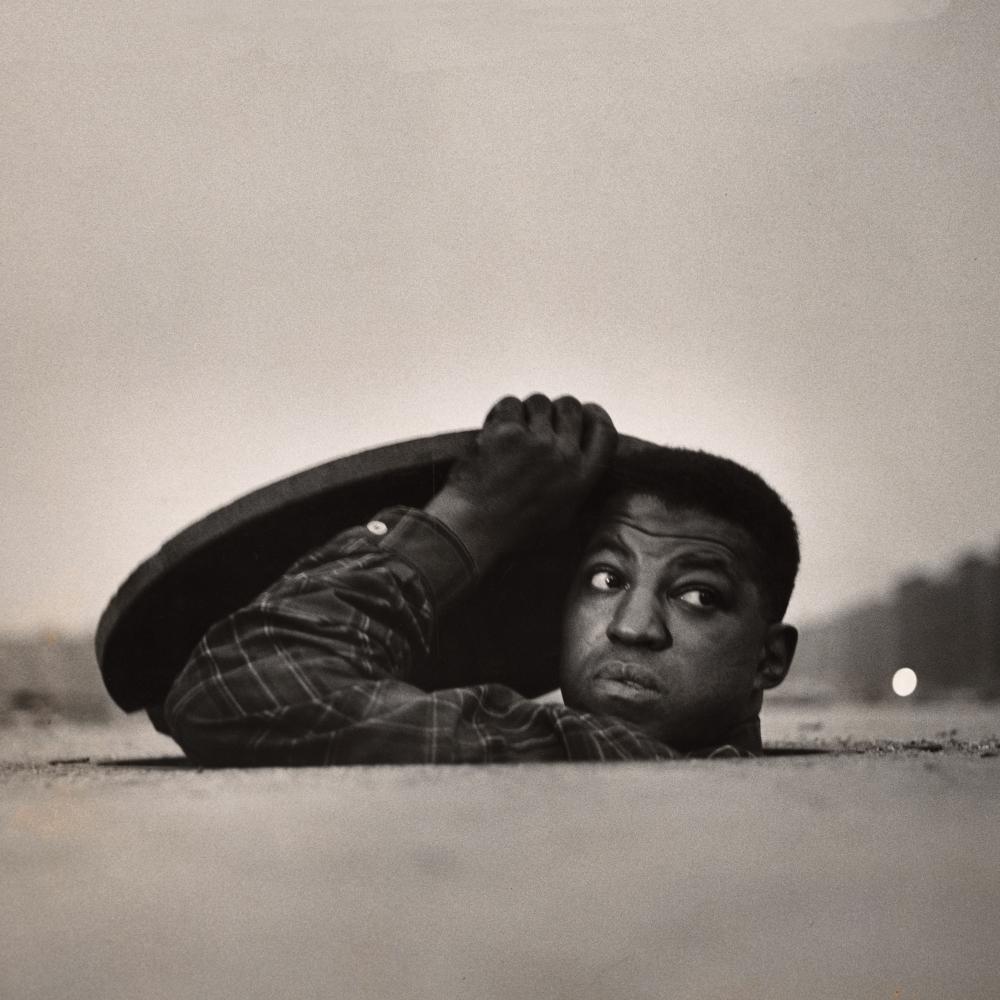

Ellison’s work is a bildungsroman that chronicles the absurd, nightmarish, surreal, and, at times, hilarious journey of a nameless narrator. He lives in an underground dwelling illuminated by 1,369 lightbulbs stolen from Monopolated Light and Power, with Louis Armstrong’s “(What Did I Do To Be So) Black And Blue” sometimes blasting on the record player. He tells his story: Twenty years earlier, Dr. Bledsoe, the president of his Black college, expelled him from school for showing a poor Black family to a white trustee, and sent him to New York City, with fake promises of employment that left him stranded.

In the Big Apple, the narrator encounters the brutal and contradictory realities of American racism and is disillusioned at every turn, from the Liberty Paints Plant with Lucius Brockway, an African American who ironically creates the plant’s trademark color, “Optic White,” to the Brotherhood, a Communist party-like organization supposedly devoted to the betterment of Black and oppressed people, to Ras the Exhorter, a West Indian Black nationalist who chases the narrator on horseback with a shield and spear, forcing him to escape down a manhole. It’s there, beneath the city, where no one sees him, that he discovers who he is as a human being without the cliches, stereotypes, and limitations others imposed on him. After a series of trials, missteps, and misadventures, the narrator is finally ready to deal with the world on his own terms. It is that search for affirmation and identity—through an African-American cultural context—that gives Invisible Man its enduring universal appeal.

The initial reviews of Invisible Man were glowing. Wright Morris of the New York Times wrote, “With this book the author maps a course from the underground world into the light.” Ellison was the first Black author to win the National Book Award, in 1953. A poll of 200 critics, authors, and editors in the New York Herald Tribune in 1965 voted the book as the most distinguished novel written by an American during the previous 20 years. In 1998, the novel ranked nineteenth on the Modern Library’s list of the 100 best English-language novels of the twentieth century. It has been translated into 17 languages.

Though a work of fiction, some elements of Invisible Man parallel Ellison’s life. Like the narrator, Ellison attended an African-American college, Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, founded by Booker T. Washington. Although he wasn’t expelled from school, Ellison left Tuskegee in his junior year in 1936 to earn money in New York, with the hope of returning to the school to earn his degree. And, like the narrator, he stayed in New York City, where he found his voice.

Ellison was born in Oklahoma City in 1913 to Lewis Alfred Ellison and Ida Milsap Ellison. Named after Ralph Waldo Emerson, Ralph was the second of three boys. An older brother died before Ralph was born, and his younger brother, Herbert, was born in 1916. His father, an ice and coal delivery man, died when Ralph was three in a work-related accident. His mother was forced to hold down a number of jobs. Ralph was a voracious reader, played football and the trumpet, and graduated from local Douglass High School. He was a music major at Tuskegee, and, inspired by his English professor Morteza Sprague, continued to read magazines and the great works of literature, including those of Hemingway, Melville, and T. S. Eliot, while working in the school library.

In 1936, Ellison went to New York City and met established Black writers Langston Hughes, Alain Locke, and Richard Wright. They encouraged him to write for several magazines, including Negro Quarterly and Negro Story. He also collected folklore and wrote for the New York Federal Writers’ Project.

Though Ellison owed much of his early writing style to Wright, he was determined to develop his own literary voice, drawing on a variety of influences. He was also wary of political agendas getting in the way. In 1967, he gave an interview to Harper’s Magazine and said:

My fiction was always trying to be . . . something different even from Wright’s fiction. I never accepted the ideology which The New Masses attempted to impose on writers. They hated Dostoyevsky, but I was studying Dostoyevsky. They felt that Henry James was a decadent, some sort of snob who had nothing to teach a writer from the lower classes—I was studying James. I was also reading Marx, Gorki, Sholokhov, and Isaac Babel. I was reading every-thing, including the Bible. Most of all, I was reading Malraux. . . . So perhaps it is the writers whose work has most impact upon us that are important, not those with whom we congregate publicly. Anyway, I think style is more important than political ideologies.

After the publication of Invisible Man, Ellison became a cultural figure of tremendous importance. He was an in-demand speaker, appearing on radio and TV and writing in major publications. He was a fellow of the American Academy of Rome, was appointed to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, was a charter member of the National Council on the Arts, and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1969.

Although Ellison declared his commitment to civil rights, younger, more militant Afrocentric Blacks attracted to the Black Arts Movement led by Leroi Jones/Amiri Baraka did not see him as an ally. Ellison’s stance that devotion to craft instead of complaint be the criteria for good writing, the fact that his literary ancestors were Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, and Fyodor Dostoevsky, among others, and his belief that African Americans were only part African, only widened the divide.

For longtime Ellison friend and noted literary scholar Charles Johnson, the struggle of Black Americans to achieve full citizenship in the United States is central to Ellison’s work. “I think Ellison is increasingly important because he was, first and foremost, an American writer,” Johnson says. “He believed in the American experiment in democracy and felt that while we have to be very cautious about the problems of the Founding Fathers, we should honor the principles that they put forward in our sacred secular documents like the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.”

“Ellison’s novel was an achievement of performance, both in terms of literature and, I would have to say, philosophical explorations,” Johnson continues, “from Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground to Wright’s The Man Who Lived Underground . . . Faulkner, Hemingway, Melville . . . all of those canonical predecessors in American literature.” Robert G. O’Meally, a professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University and the editor of a collection of essays on Ellison’s work, recalls reading Invisible Man in high school, trying to make sense of the book:

What struck me at first about the novel was that it was very difficult to read. I could feel the power of the eloquence there, and the power of the intellectual force behind what’s being [written]. Here is a Black writer who exceeded all of the expectations set up by my experience. He seems to know all about the kind of little tricks of the trade when it comes to sci-fi and that sort of thing. And he certainly knows about Black life in America, but he’s challenging me to figure out what he’s doing.

So that was my first encounter with it. I read it again, when I was a freshman at Stanford University, which seemed very pertinent to me, coming of age, as part of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s. So when the Black Panther party was saying, You must do this, Ellison said, Wait, what are the motives here? What’s behind all of this? Ellison encouraged you to be very affirmative of Black American culture—that comes through all his writings. But he also is warning you that you must examine the life around you.

Larry Neal, a poet and critic who coedited Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing, with Jones/Baraka in 1968, was initially dismissive of Ellison’s white literary models. He later reversed his opinion after researching Ellison’s work in the forties. “It is now my contention that of all the so-called older Black writers working today, it is Ralph Ellison that is most engaging,” Neal writes. “All black creative artists owe Ellison special gratitude. He and a few others of his generation have struggled to keep the culture alive in their artistic works.”

After Invisible Man, Ellison would publish two excellent books of essays, Shadow and Act in 1964 and Going to the Territory in 1986. But the world was anticipating the publication of his long-awaited second novel. Ellison had been working on it since the late fifties and had published excerpts of it in bits and pieces. But a portion of his approximately 350-page manuscript was destroyed in a fire at his country house in 1967. For the rest of his life, Ellison would work to recreate the intricate transitions central to the novel, to no avail. The novel remained unfinished when he died.

Many wondered why Ellison didn’t finish the second novel. Did he have writer’s block? Did he feel that he needed to prove to the world that his first book was not a fluke? For Columbia professor of English and African-American studies Farah Jasmine Griffin, those questions must have haunted Ellison.

“I think there must have been tremendous pressure, that your first novel, out of the block, is the game-changing novel, if that’s what you feel like you have to live up to,” Griffin says. “If you’re only going to write one novel, and it’s Invisible Man, you don’t have to write anything else! When you sit down with that novel, you cannot deny the seminal accomplishment and achievement. He set himself a very high standard and high goals, with the American literary tradition in mind. [With] Black people at the center of that is a major literary accomplishment. There’s no denying that, no matter what you think about the man or his politics.”

After Ellison’s death, John F. Callahan, Ellison’s literary executor and retired professor of English at Lewis & Clark College in Oregon, and his assistant and former student Adam Bradley edited thousands of pages of the novel’s manuscript. They published the 368-page Juneteenth, and Three Days Before the Shooting was published in 2010 as the full-length 1,101-page version for scholars. Both books tell the story of a race-baiting senator of unknown ethnic identity.

Bradley, a professor of English and African-American studies at UCLA and the author of Ralph Ellison in Progress: The Making and Unmaking of One Writer’s Great Novel, teaches Invisible Man to today’s students, who he says would rather read a book online instead of an old-fashioned bound version.

“[Students] can really get a sense of how Ellison wrote Invisible Man through the manuscripts,” Bradley says. “And they are a fascinating study, for someone figuring out how to write their first novels. And so you can see the agony of those six and a half years of composition, as well as the joys of the moments of discovery and inspiration, and it’s knitted throughout the multiple iterations. He wrote episodically . . . and seeing the different versions and imaginings he would have on single scenes, was really striking. And then also to see his notes—he was a voracious note taker—about his own work . . . about the nature of his craft, and the choices that he had to make on fragmentary tables of contents and outlines of the structure of the book. You’ll find character studies. You’ll find any number of things that inform how he went about writing the book.”

Not surprisingly, given his studious approach to writing, Ellison enjoyed teaching. He taught at Bard College, the University of Chicago, Rutgers University, and New York University, where he taught literature from 1970 to 1979. One of his most devoted students in the early seventies was Don Katz, who went on to become a writer and the founder and executive chairman of the audio and podcast company Audible.

“I found out that [Ellison] taught a small colloquium, mostly for upperclassmen, and I talked my way into it,” Katz recalls. “I couldn’t believe the depth of the teaching, because Ralph, it turned out, was a deep and profound student of American vernacular, going way back and to a period when the voice of American literature was studied very technically and deeply in the twenties by people like I. E. Richards and Constance Rourke on folklore and the like. I reread Twain and other people through Ellison’s sophisticated teaching. And I felt like I was learning to read all over again. He taught me how to think about the sound and concept of literate listening, which is basically what I evoked when I started Audible.”

Katz’s company features an audiobook of Invisible Man with the voice of the narrator by noted actor Joe Morton, who also adds his voice to the Audible-produced show Jazz in the Key of Ellison, a theater revue dedicated to Ralph Ellison’s writing on jazz and his favorite musicians. The first show, which featured Wynton Marsalis and singers Patti Austin, Angelique Kidjo, and Catherine Russell, debuted at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center on November 1, 2016.

“I had been thinking for years that I had to figure out a way to honor Ralph: His teachings are the spiritual guidance that created Audible and brought the integrity of the literary experience of reading into modern culture,” Katz says. “The concert was an idea of an evening that melded together the sounds of his words and the sounds of the jazz he loved, with visuals. Joe Morton reads [from Invisible Man], with a walking bassline and a really sophisticated tenor sax underneath. It had this amazing opening, and then it did a road show version that just ended.”

When the nameless narrator in Invisible Man emerges from his underground dwelling to confront the world on his own terms, he asks this enigmatic question, “Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?” Ralph Ellison’s book speaks to us today on multiple frequencies: The issues of race, ethnicity, and identity he wrote about in 1952 are still very much with us. The police brutality in the novel is alive and relevant, as evidenced by today’s myriad Black Lives Matter protests. Complex issues of autonomy and power at historically Black colleges and universities are as complicated today as they were when depicted in the novel. Like Ellison’s protagonist, we must be armed with what he termed the sense of “tragic optimism” born of the blues, with an improvisational, jazz-like adroitness to roll with the punches that modern life will throw.